Geoff Wilson in Kabul

Air traffic controller Geoff Wilson has recently returned from in Kabul in Afghanistan, where he was part of the International Security Assistance Force. Plus went to talk to him at RAF Lyneham near Swindon, about how his love of maths and planes combine in his career with the Royal Air Force.

"I always wanted to go into the Air Force", says Geoff. "When I was about six, we went on holiday to Lincolnshire, and sat outside an airfield and watched the aeroplanes - it captured my imagination." At school in Barrow-in-Furness (near the Lake District), Geoff took A-levels in pure and applied maths, physics, and geology (in 1983). He says this choice was natural because he's "more like Mr Spock than Dr McCoy!". Working on the principle that if he didn't get into the Air Force, he would still need to find a job he enjoyed, he applied to what was then Coventry Polytechnic to do a BSc in computer science.

If at first you don't succeed...

During his final year at school Geoff went through selection with the RAF, but didn't make it. Selection is basically aptitude testing, and varies depending on the role the applicant wants to fill. Geoff tested for pilot, navigator, and air traffic controller. Selection involves a lot of mental calculation, particularly for pilots and navigators. "You're here, you've got to get there, the distance is so far, you estimate the speed you think you can travel at and estimate how long it will take you." No calculators were allowed, because "hurtling along 100ft above the ground at 500mph with someone shooting at you, you can't stop and get your calculator out!"

The Phantom air defence aircraft [Photo courtesy of Vic Flintham]

So Coventry Poly it was. Geoff enjoyed his first two years, even though the Air Force remained his ultimate goal. At the end of the second year he failed Business Studies, but the problem was put on hold because the third year of the course was an industrial placement. He got a job programming with Rediffusion Simulation, a private company specialising in full-motion flight simulators, developing computer systems to train navigators how to use the air-to-air radar systems carried by Phantom air-defence aircraft. These sit in the nose of the plane and scan side to side, producing a cone of visibility. The result is that objects far enough away to be completely inside this cone are easily visible, but nearby objects are hard to spot. To help solve this problem the image is manipulated from a cone to a rectangle by stretching out the nearby part of the cone. This distortion increases the part of the picture devoted to objects nearby - but at the cost of distorting reality. For example, a plane travelling straight towards the radar will appear to be travelling on a curve. The simulator Geoff was working on was used to train navigators to develop the ability to interpret these radar pictures and get an accurate mental picture of what's going on around the plane.

...try, try...

In the end, Geoff didn't return to university after his industrial placement year, partly because of the failed business studies course but also because, through personal contact with an RAF recruitment officer, he managed to be allowed to do selection a second time - and this time he passed. But nothing in life is simple, and Geoff fell at the next hurdle, failing the medical because of eyesight problems. "So at the end of the placement I was out on my ear."

Having decided not to return to his studies, and having been rejected by the Air Force, Geoff continued to work for Rediffusion Simulation. After he had worked there for 18 months in total - just five years after he first applied - the Air Force changed their minds and accepted Geoff. How did he manage to persuade them? "A lot of letters"!

...try again!

Finally Geoff's persistence had paid off. He signed up for a sixteen year tour of duty with the RAF in 1988. First came officer training at Cranwell. "The first six weeks was all the sort of stuff you see on TV, shouting at you, polishing this, polishing that, folding that, ironing this, marching up and down. The second six weeks was leadership training - we seemed to spend most of the time running around fields carrying pine poles! The final six weeks was managerial training and some war gaming. Then a final bit of shiny parade work to make you fit for graduation."

The next step was specialist training - another 18 week course. Geoff learnt about the theory behind it all - how navigation instruments work and how to use them. Everything has to be quick - almost instinctive - in air traffic control, because it's a pressurised job where the ability to think on your feet is crucial. Mathematical principles are also important to understand - for example, the principles behind Mercator projections, used in most maps. "If you get your atlas out, and you look, say, from here to New York, you'd probably think of going via the Isle of Man, straight across to New York. But when you're flying, because you're on a sphere, the fastest route is one called the great circle route, which is a direct line, and if you then extrapolate that onto your atlas, you're actually flying out over Penzance, south, because New York is actually a lot further south than us."

When Geoff was commissioned, RAF recruits had to have O level maths to be eligible. They now must have GCSE maths and two A/A2 levels. Although his A-level maths and further maths weren't required, Geoff says the logical thinking and reasoning skills they taught him have been very useful.

Understanding air pressure and altitude calculations are among the most crucial parts of his job. The crew of a plane measure how high they are using an altimeter, which is just a barometer which gives readings of height based on the pressure. But pressure varies from place to place and time to time, and ground level is different from sea level. So using an altimeter without making errors requires constant alertness and repeated calculations, all done "on the fly".

If you would like to know how altimeters work and how they are used in air traffic control, read Altimeters, accidents and air traffic control, written by Geoff for Plus.

The Harrier is capable of vertical takeoff and landing [Photo courtesy of Vic Flintham]

The second six weeks of specialist training covered the theory of radar, and the final six weeks involved simulator exercises and assessment. Those that passed were then assigned to a unit and start training with real aeroplanes. Geoff's first tour was at RAF Wittering in Lincolnshire. "Wittering didn't have any radar, it was just a tower and talkdown. Every unit is different. Wittering, with the Harriers, was all up and down, short takeoffs, short landings. You needed eyes on the back of your head and somebody else to help you. You train in various positions - ground controller, who deals with aeroplanes taxiing out, tower controller, who deals with flying around."

Geoff spent 30 months at Wittering, which is shorter than most domestic tours, because an air traffic controller who spent too long at a non-radar base would get rusty. Next he spent four years at RAF Coltishall, just outside Norwich. "When you arrive in a new unit, you've got to start again. You shadow someone until you're good enough to do it on your own."

Then Geoff was transferred to Prestwick, outside Glasgow. Prestwick controls military aircraft crossing some of the world's busiest civilian airspace - the route taken by transatlantic traffic up from London, over Manchester, up to Carlisle and then to Scotland. He explains that the importance of Prestwick is a legacy of the Second World War, when Britain's airfields were built on the East Coast, because that was where the threat had to be repelled. "But subsequently we've gone to peacetime ops, we do a lot of low level flying, and all the hills are on the west coast. So all the aeroplanes have to get from the airfields on the east to the hills on the west." But unfortunately this means crossing civilian airspace, where military craft have to give way.

Geoff says "it could get stressful" - which from the sound of it is typical military understatement! The real stress at Prestwick came during the big international Maritime Military Exercises, held twice a year. "They've got flotillas of ships and submarines, and various air forces would mount attacks, and simulate naval warfare. That would get busy, because all things military always work in waves, so a wave would launch, you'd have to get aeroplanes out from the east coast, across to the Atlantic Ocean on the west coast, and then you could sit back for a cup of coffee, and then they would all come back again."

Troops and equipment were carried out to Kabul in Hercules transport planes [Photo courtesy of Vic Flintham]

Although Geoff still enjoys doing air traffic control, neither he nor the Air Force are the same as they were when he signed up in 1988. He is now married with two young children, and although at first he enjoyed new postings because they gave him a chance to see the country - and in fact the world - he feels his children need stability. He has also spent seven months on unaccompanied tours since becoming a father, which he and the rest of the family have found difficult - four months in the Falklands in 2000, and most recently a three-month tour in Kabul.

"A year and a week after I got back from the Falklands I got put on 48 hour standby to go out to Afghanistan. Lyneham was told to provide an air controller with a full set of tickets. There were three of us, and I was the most expendable! I had two days to get kitted out and draw equipment, then brief ops training. It was a real fast ball, I wasn't expecting it." Then followed a very stressful period of on-again-off-again - in the end Geoff spent three long months on standby.

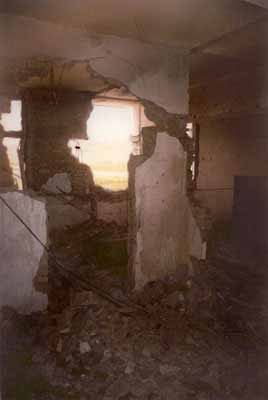

The control tower in Kabul

Up close - a rocket crater in the control tower

British military in Afghanistan are serving as part of the International Security Assistance Force, whose role is to stabilise the situation. The first British military to arrive were the Paras, who provided on-the-ground troops in Kabul itself. Then the Air Force went in, to set up an APOD (air point of disembarkation) - military speak for an airfield. Then it was Geoff's turn, as part of a team of air traffic controllers.

"The Afghan government was trying to get the airport open as an international airport. We had no radar, it was just tower. In a way it was easy because then all the responsibility is the pilot's - you fly on the rule 'see and avoid'! Bear in mind the airfield hadn't been used for a long time - the Taliban banned all sorts of flying apart from military. Afghanistan has got the largest concentration of land mines in the world, and the locals knew that the airfield had been made secure, so they used it as a shortcut! Within a month they got the hang of it and knew to watch for aeroplanes, but you still had to watch for people driving down this nice big road, or walking across it!"

Onwards and upwards

Geoff's sixteen year engagement with the Air Force is now drawing to a close, and he intends to move on to a job in computer development, perhaps working on developing air traffic control software, for which he would obviously be well-placed - "someone straight from college isn't going to understand the finer nitty gritty of air trafficking". To this end, he is working for an Open University Diploma in Computing for Commerce and Industry. "I think I'd prefer to go into a management role, because that's a skill you get as an officer. I'm not going to be the smartest Java programmer in the world, but I can say 'I've done Java, and I can manage things'."

Geoff has seen enormous changes in the Air Force during his engagement. "Once the Berlin wall came down everything changed. The air force that I joined wasn't an expeditionary air force, It was part of 'Fortress Britain'. Having kids changed it for me too, because you suddenly find yourself being dragged away from them, and they're standing at the door crying." But Geoff wouldn't have missed it for the world - he says that his engagement has been "fantastic" and that he would recommend working for the Air Force to anyone.

Who knows what changes the next sixteen years may have in store - for Geoff and for the RAF?

About this article

Helen Joyce is editor of Plus. For this article, she interviewed Flight Lieutenant Geoff Wilson at RAF Lyneham.

She is very grateful to military aircraft expert Vic Flintham (Post-war military aviation), who kindly supplied her with the pictures credited to him in the text, which he assures her are from the appropriate periods and carry the appropriate markings - thus protecting her from floods of emails from nitpicking planespotters!