Climbing the Twitter ladder

What's your place in the Twitter network?

How popular and successful are you? Not as much as your friends is the sad answer, at least as far as social media are concerned. A recent study of Twitter shows that the vast majority of users are less popular and successful than the people they follow, on average. Only a tiny minority right at the top outperform their "followees".

Twitter isn't the only place where this happens. Back in 1991, a good fifteen years before the social media explosion, the sociologist Scott L. Feld observed that most people have fewer friends than their friends have, on average. When you ask them, however, people tend to say they believe that they've got more friends than their friends — which is why the phenomenon came to be known as the friendship paradox. When it doesn't refer to personal friendship, but other things like social media connections, it's known as the generalised friendship paradox.

In the Twitter study the generalised friendship paradox reveals itself to a shocking extent. Over 93% of the users that were studied have fewer followers than those they follow have on average. Only users with more than 155,000 followers escape this humiliation — and there aren't many of those, since only 1% of users have more than 460 followers.

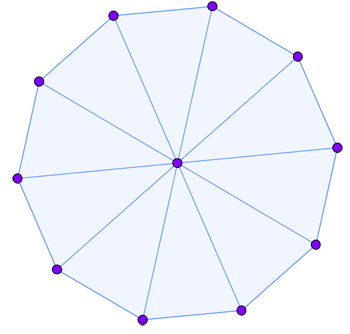

In this social network all the outside nodes have 3 "friends" while the inside one has 10. The average number of friends of friends of outside nodes is therefore (2 x 3 + 10)/3 = 5.3. Since this is greater than 3, all the outside nodes have fewer friends than their friends, on average, which means they suffer from the friendship paradox.

What does this tell us about Twitter network? One way in which the generalised friendship paradox can arise in a social network, be it online or in the "real" world, is that the network contains a few people that are extremely highly-connected. If you are friends with such a person and work out the average number of friends your friends have, then the highly-connected person can drive that average sky-high (see the example on the left). In this case, the friendship paradox is only a statistical artifact: the number of friends people have can be very similar for everyone apart from those few highly-connected people. The network then looks like a collection of stars with the highly-connected nodes at their centres.

A more interesting possibility is that, in a form of glory hunting, people prefer to connect with those that are equally or better connected than themselves. This creates a hierarchy in the network, with the poor lowly-connected nodes at the bottom and very highly-connected nodes at the top.

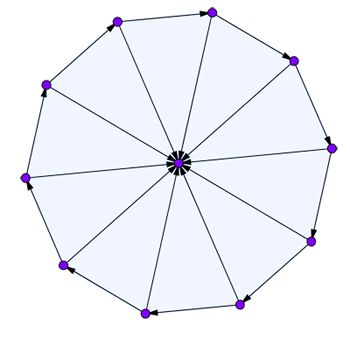

The authors of the Twitter study, Naghmeh Momeni and Michael Rabbat of McGill University in Canada, wanted to know which of those two things cause the generalised friendship paradox on Twitter, so they analysed Twitter data involving 5.8 million users and over 200 million tweets. The Twitter network looks a bit different from an ordinary friendship network because a connection is not necessarily mutual: if you follow someone, that doesn't necessarily mean they follow you back. So while an ordinary friendship network can be depicted by nodes representing people and links between nodes representing friendship, in a Twitter network the links become arrows with their direction telling you who follows who (see the image on the right below).

A Twitter network is directed: an arrow from one node to another means that the first node follows the second. (This isn't a real Twitter network, it's just an illustration of the idea.)

The obvious thing to look at when it comes to Twitter is the number of followers people have — and as we've already seen, the generalised friendship paradox is blatant when it comes to followers. But many followers doesn't necessarily mean big impact: if you don't tweet very often, or are so overwhelmed by information that you miss out on tweeting the stuff that's likely to go viral, your Twitter presence may not be as influential as that of other users with fewer followers. That's why Momeni and Rabbat also looked beyond simple follower numbers. They included measures of a person's activity on Twitter, such as the total number of tweets they sent, and measures of their influence, such as the fraction of their tweets that got retweeted and the average number of retweets per tweet.

For these numbers too it's possible to see if there's a generalised friendship paradox. For example, given a user, call them A, you can compare the fraction of their tweets that got retweeted (FTR) to the average FTR for the people who A follows. If that average is higher than A's FTR, then A suffers from neighbour superiority as far as average FTR of the people A follows is concerned.

But as we've already seen, the ordinary average is a crude measure since it can be skewed by a few highly-connected and highly successful nodes. This is why Momeni and Rabbat also looked at medians. In the FTR example, list the FTR's of all the people that user A follows by size, and pick the number on that list that lies right in the middle. That's your median. If that median is higher than A's FTR, then this means that more than half of the people who A follows have a higher FTR than A — which means that A suffers from neighbour superiority as far as the median FTR of the people A follows is concerned. (See here for more about the median and other types of averages.)

The results of the study are interesting. If you're disappointed with a lack of reactions to your tweets, you can take solace in the fact that 75% of users in the study never got retweeted. It seems that people on Twitter like to read tweets, but don't often retweet them. What's more, the Twitter network doesn't look like a collection of stars, as described above, but contains hierarchies: people tend to follow people with higher, or similar, attributes than themselves, rather than "following down". This trend to "follow up" is so strong that even users in the top 0.5% experience neighbour superiority of some kind. (Interestingly, though, the hierarchies can be different for different attributes: if you order user in terms of the total number of times they were retweeted and then order them in terms of follower numbers, you'll see different hierarchies emerge.)

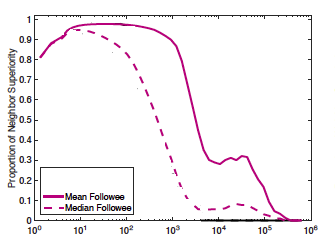

The horizontal axis measures number of followers and the vertical axis the proportion of users with that number of followers that experience neighbour superiority with respect to the people they follow: in other words, the people they follow have more followers (on average or median) than they do. The solid purple curve represents neighbour superiority in terms of the ordinary average and the dashed purple curve neighbour superiority in terms of the median. In both cases the curve first increases, then reaches a plateau, and then decreases. Figure is from this paper, CC BY 4.0.

Intuitively, you'd think that the higher a user's attribute, the less likely they are to experience neighbour superiority for that attribute. For example, you might think that the more followers a user has, the less likely they are to experience follower number neighbour superiority. But that's not always the case: as the graph on the left shows, the likelihood can even increase at first, then settle down on a plateau, before decreasing when quite a high number of followers is reached. This indicates that people with few followers are happy to follow "across" as well as up, but as the follower number increases, people are more likely to follow only up, until they have so many followers that neighbour superiority decreases again.

What lessons can we draw from all this? In terms of Twitter, you might deduce that users are shallow: it doesn't matter how interesting your tweets are, if you're not successful enough, people won't follow you. If you want to reduce the amount of neighbour superiority you suffer from, it's not enough to slightly increase the relevant attribute: you really do need to be way up in the top percentile to avoid it.

In more general terms, the study sheds some light on how the structure of a network is related to the influence nodes have on each other, and provides tools for studying this relationship in other networks too. This can be useful in a range of contexts, from understanding the spread of information (or misinformation), to finding optimal marketing strategies, or understanding the spread of diseases.

The paper Qualities and Inequalities in Online Social Networks through the Lens of the Generalized Friendship Paradox by Momeni and Rabbat has been published in PLOS ONE.