Burning buried sunshine

Next time you fill up at the petrol station, ponder this figure - it took over 23 tonnes of plants to produce each and every litre of petrol you pump into your tank.

Jeff Dukes, from the Carnegie Institution of Washington, came up with this astonishing figure while studying how efficiently fossil fuels store sunshine as energy. "Fossil fuels developed from ancient deposits of organic material, and thus can be thought of as a vast store of solar energy," Dukes says. Plants use photosynthesis to turn the sun's energy into carbon, which is then converted into gas, oil or coal (known in the coal industry as buried sunshine). Over millions of years the plant matter, trapped in peat swamps or as sediments on the sea floor or lake beds, is converted by heat and pressure to form fossil fuels.

It turns out that this process is a very inefficient one, as Duke discovered when he used existing data to estimate how much carbon was lost at each stage. Only 9% of the carbon in the original plants makes it to coal, while just a tiny proportion - 1/10,750 - remains in oil or gas.

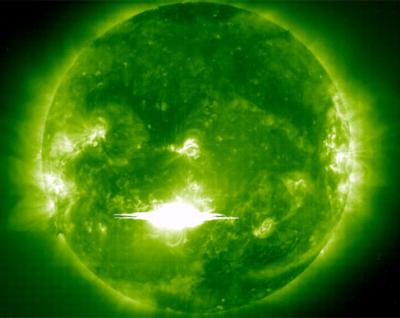

Buried sunshine - fossil fuels are a vast store of solar energy (image courtesy of NASA)

Dukes used these estimates to calculate how much original plant matter was responsible for the fossil fuel we are burning today. For example, to produce one litre of petrol it takes 1.29 kg of oil, of which 85% (1.1 kg) is carbon. And as only 1/10,750 of the carbon remains from the plants that were buried millions of years ago, our one litre of petrol is the result of 1.1 x 10,750 = 11,825 kg of carbon from ancient plants. Finally, as plants are approximately half carbon, that means that 23.65 tonnes of plants were required to make just one litre of the petrol available at your local station.

"Every day, people are using the fossil fuel equivalent of all the plant matter that grows on land and in the oceans over the course of a whole year," says Dukes. In fact, in 1997 - the year he uses in the study, chosen as all the data was available - the equivalent of over 400 years' worth of plant matter was burnt as fossil fuels.

So how did something produced so inefficiently become our major source of energy, supplying 83% of our energy needs? Despite the inefficient process, Dukes says that, over the last 500 million years, fossil fuel deposits grew large enough to offer us an ample and relatively cheap energy source for the past 250 years. But that supply is not infinite. "Fossil fuel consumption is widely recognised as unsustainable," says Dukes in his paper "Burning buried sunshine", to be published in the journal Climatic Change. "However, there has been no attempt to calculate the amount of energy that was required to generate fossil fuels, one way to quantify the unsustainability of societal energy use."

Dukes considers his calculations to be good estimates based on available data, but says that because fossil fuels were formed under a wide range of environmental conditions, each estimate is subject to a wide range of uncertainty. However, despite this he hopes that his research will make people think about our use of fossil fuels and encourage the search for other more sustainable sources of energy.