Career interview: Science communicator

Alison Boyle's work as a science journalist will be familiar to regular Plus readers - her article From quasicrystals to Kleenex appeared in issue 16 of Plus.

At the time of writing the article, Alison was studying for a Masters in Science Communication at Imperial College London. She is now working as an exhibition researcher for Antenna, the science news section of the Science Museum in London, and here she tells Plus about her career to date.

Alison's first degree was in Galway, Ireland, where she studied for a BSc in Physics between 1994 and 1998. At school, she had taken a "mixed bag" of subjects - in Ireland, students study between six and eight subjects until they leave, unlike the early specialization required for A-levels - and Alison studied German, Geography, Physics and Accounting as well as English, Irish and Maths, which are compulsory. She says she chose physics because she wanted to do one science subject, didn't like chemistry and although she liked biology, to her it seemed to involve too much "learning things off by heart and drawing things"!

The choice of physics for her degree subject wasn't the most obvious one. Her lifelong interest in writing meant that everyone she knew had always assumed she'd do an English degree. But an open day at the University of Galway, where she talked to people on the astronomy programme, changed her mind.

Luckily, Alison enjoyed the maths which is such a major part of a physics degree, probably because she had always found maths quite a friendly subject. "I've never really had this fear of maths that a lot of people seem to have, probably because my mum taught maths in school, so when I was a kid she would help me." It was quite a culture shock when Alison went to university and discovered that her mother didn't know everything any more, and instead she had to fend for herself!

Polyhedra displayed in the maths gallery at the Science Museum

Alison says that her interest in maths is in "using it as a tool - because it is such a powerful tool. When you're doing quite abstract maths in university it can be really hard - but you sit down with a group of people and you just get through it and it's really satisfying to actually get it to work."

After her B.Sc., the next step in Alison's career was to study for a Masters degree in Astronomy. This was offered by the University in Galway, but actually involved spending six months in Portugal, and another six in Oxford, "which was a big selling point!" Choosing to specialize in astronomy was straightforward. "Astronomy was the part of science that I always really liked and the main appeal of doing a physics degree. I guess like a lot of kids I was just fascinated with it." However, the advanced study of astronomy doesn't bear much resemblance to the popular image of staring through a telescope at the sky. "It's much more technical and most of it boils down to computer programming."

The first six months of her Masters degree was basically a crash course in Astronomy. Lecturers from all over Europe would visit for a week at a time to give an intensive course in their particular area - covering everything from spotting objects beyond Pluto to plasma physics. The next six months, at the Astrophysics Lab at Oxford, were spent doing a research project. "We were looking at data from the Hubble space telescope, searching for variable stars. Certain stars vary in their light output - you get quite regular patterns - and we were looking at something called a globular cluster. These are groups of old stars - the oldest objects in the galaxy - and looking at those you would hope to get an indication of the age of the universe.

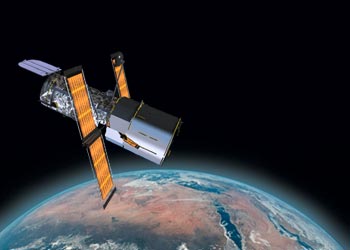

The Hubble space telescope, image courtesy of NASA

"We used optical images from Hubble. We were trying to pick up changes in light of a certain regular frequency, from which you can get some idea of what kind of star you're looking at, because different types of variable stars vary over longer or shorter periods. Sometimes it's to do with the size of the star and the various compositions of what kind of gas is left in there and what isn't. Radiation pressure inside the star pushes it outwards, but then gravitational collapse tends to push it inwards, and it's just a constant fight between the two of them. You can also see variation due to other factors, for example stars in a binary system, where a faint companion can block out light from a brighter star when it passes in front of it. My project found around ten variables of different types in the centre of a particular globular cluster."

By this time Alison had decided to return to the University in Galway to do a PhD in Astronomy. She started work on a couple of short projects, trying to find optical signals from pulsars. Pulsars are neutron stars - very dense stars - which spin around and emit very regular signals. "What we were trying to see was the peaks - depending on what direction the pulsar is turned you'll get a blast of light or you won't get anything, so you time it and check how regular the clock is. We were trying to find optical pulsars, because mostly you detect them in radio wavelengths. We would look where we knew there was a radio source and see if we could find an optical counterpart for it. The two signals would be from the same thing, but the optical signal is a heck of a lot weaker, and so much harder to spot."

But very soon after starting she realised that this wasn't really what she wanted to do. While she had been in Oxford, she had heard about the Masters in Science Communication at Imperial College, but it was already too late to apply that year.

"What I was doing in Galway was great, but I just realised it wasn't what I actually wanted to do. It will open certain doors for you but if you don't want to go down that route... and it is three or four years of your life. Having had a passion for English originally, I knew that what I really wanted to do was to try and combine the two and do science journalism. So I decided to leave the PhD and apply for the Science Communication course at Imperial College."

Alison arrived at Imperial College in September 2000. She explains that the course "is geared towards people who've done science before, to degree level or maybe a bit more than that. A lot of people on the course had PhDs or had worked in industry already." It suited her down to the ground. "I loved it. It broke down my conceptions of what science is about. There was a crash course through the history and philosophy of science, and they taught us how to argue things properly, instead of just saying 'well the maths works out, Q.E.D. it's right'. "

As well as the theory behind science communication, Alison also studied more practical things, like web design, writing, TV and radio. "There was also a museums course which I did, which is how I ended up in here!"

A Penrose tiling modelling a quasicrystal

During the year Alison wrote an article on tessellations (tilings) as part of her coursework. She decided to try to get it published, but her lecturer told her that the subject would make that quite tricky. As she discovered, there aren't that many magazines that run articles on abstract maths topics - which is how she found Plus. "It was a lot harder to do than a fluffy cuddly animal story because it was abstract. But researching it was really good fun because it although it the topic was abstract, there is also an application to crystallography - it wasn't just about creating patterns, although I think that in itself is something very beautiful. The problem is that for most science publications, stories have got to be on cutting-edge new technology, which is not always the easiest thing to find in maths, because the maths is often quite old by the time the technology has caught up with it."

She also worked the odd Saturday at Science Line, a free public service allowing members of the public to call (0808 800 4000) and ask any science-related question under the sun. Callers are put through to a panel of scientists who will either answer their question directly or ring them back after further research. "You get this amazing mix of questions. You get little kids saying 'what does H2O mean?' and then you get someone saying 'I've got this theory about special relativity and I'm going to tell you all about it'. A lot of it is children who want you to do their homework - which you obviously can't do! It's not a health service but sometimes you will get people asking tangentially health-related questions, and if it's something we think we can answer scientifically we will, but we wouldn't give people health advice. You'll just get a lot of people ringing up saying 'why is this thing I've seen happening? Can you explain it?'. Sometimes you can, sometimes you can't. If we don't know the answer, we will contact an expert who can help - we try never to leave a question unanswered."

During and after the course, Alison wrote a couple of articles for New Scientist. (You can read these articles at New Scientist's website - although you normally have to pay to use the site, if you just want to read these articles you can do so by joining for a free seven-day trial and searching under Alison's full name.) Although she liked the idea of being a fulltime freelance writer, she couldn't see it paying the rent - especially in London. Alison says it was a "scary time", trying to decide what to do next - and then a few jobs came up for researchers at the Science Museum. "I hadn't really thought about this sort of job because I really wanted to work in journalism, but the jobs that were going in the museum were for Antenna, which is the science news part of the museum. As far as I know it's the first time news stories have been covered in a museum setting. If you make a gallery it's usually going to be there for quite a long time - anything from five years to more than thirty - whereas we do news stories, and get mini-exhibitions up in just ten days. The appeal for me was that it still had the journalistic side to it but it was a different way of seeing what you could do."

Is climate change causing ice-cap collapse? (An Antenna rapid at the Science Museum)

As well as presenting news items, Antenna puts up "feature" displays, for example the current one on climate change, on which Alison has spent a lot of time. For features, Antenna looks at the science behind big issues. These exhibitions stay up for about six months at a time. "This is a good time to do an exhibition on climate change because people are surer about the science and it's a little less woolly about whether or not it's happening. We spoke to a large number of scientists who say that climate change is a reality - obviously there are sceptics, but the general consensus is that it's happening." A small team of researchers put this exhibition together. "Day to day there was the initial research - who are we going to interview, what kind of things are we going to cover. Then we wrote the text for the panels, came up with ideas for interactive games, and drew up specifications for software contractors. We wrote more in-depth information for the computer touch-screen points - about 12,000 words of text! We've got some objects in - for example, a model of the ENVISAT earth climate satellite that the European space agency lent to us. There's all kinds of paperwork you've got to go through, and there are safety issues bringing in big objects. You end up doing quite a lot of everything, which is why the job is such good fun. You're not just writing, you're not just doing research."

Alison explains that one of the main challenges of her job is that the target audience of a museum is so broad - "everyone from an 8 year old to an 80 year old. We can't just chuck in lots of jargon, and we can't assume that people will come in knowing what it's all about. We get a lot of people who do, but we also get people who aren't so sure at all. Whereas something like New Scientist is a bit more specialised, so in some ways it's easier to write for, even though you might have to go into more detail. There are things you can take for granted that you don't need to explain.

"At the moment I work on the news exhibitions. They generally go on what we think is the biggest story of that week. The team will all sit down and we'll decide what we think should run. We try to cover quite a range of stuff. We have to consider what is suitable for a museum format as well - for example, a quantum physics story is a bit tricky for us because you can't immediately think of a suitable object that you can put in a case. We like to have objects where we can, because it's something we can do that no other medium can do."

Something no other medium can do (Picture taken at the Science Museum)

The week we talked to Alison, Antenna was running stories on cloning, ice-cap collapse in Antarctica, tiny batteries that hopefully will be able to power artificial hearts, and horse's legs behaving like pogo sticks.

"It's hard to get maths stories in, but eventually you realise that so much of what you do is maths-related anyway. Whenever you read a paper to get the story behind the news, it will be full of maths no matter what it is, even a biology story because most biology is down to maths these days anyway. You can't ignore the fact that there's maths in everything - even though a story may not explicitly be presented as about maths, that's what it will come down to in the end."

About the author

Helen Joyce is editor of Plus.

Since this interview was conducted, Alison has moved on to new jobs — if you're seeking information about a career as a science communicator, please don't contact her. You can find useful information on the website of the Association of British Science Writers and on Psci-com.