Distributed systems and ambiguous histories

Imagine you are standing at the ATM at the airport, just about to head off on your long awaited summer holiday. It seems you and the bank don't agree about when your pay was deposited and when a withdrawal was made, resulting in a hefty overdraft fee and one less G&T by the pool! Catastrophe! And one that hinges on the definition of events in computer science, and how to order them.

How many sleeps?

A simple example of a program:

BEGIN

n = DAYS("25/12/2017", TODAY())

OUTPUT "Only " n " sleeps till Christmas!"

OUTPUT "Don't forget to be good!"

END

When most of us think of how a computer program runs, we think of it as a series of distinct events occurring one after the other (such as the very simple example in the box on the right). Without much thought, we have assumed that there is no ambiguity in the order in which these events occurred. The history of the program would be clear, something we could follow on a linear timeline.

This isn't surprising, explains Leslie Lamport, principal researcher at Microsoft Research and winner of the 2013 Turing Award. "The concept of time is fundamental to our way of thinking. [Our sense of time] is derived from the more basic concepts of the order in which events occur." The concept of being able to order events, according to some timeline, pervades the way we think of any set of events, including those that occur inside a computer program.

Programs with such an unambiguous history are called processes: a sequence of events where it is clear which events happened before others. In mathematics this set of events is said to be totally ordered. For any two events in the process (say, A and B), you can always say which happened first: either A happened before B or B happened before A.

Here "happened before" is called a relation, something that orders a set of objects, in this case, the set of events. A more familiar example is the relation "less than" () that orders all the integers. For any two distinct integers a and b, you can always say that a b or b a. The integers are totally ordered by the relation "less than".

Distributed systems

Unsurprisingly, as this is the way we intuitively perceive events, the first programs in computer science were written as processes. But since the late 1970s there is another option: writing programs as distributed systems. A distributed system is a bunch of distinct processes occurring in difference places, but that communicate with one another by exchanging messages.

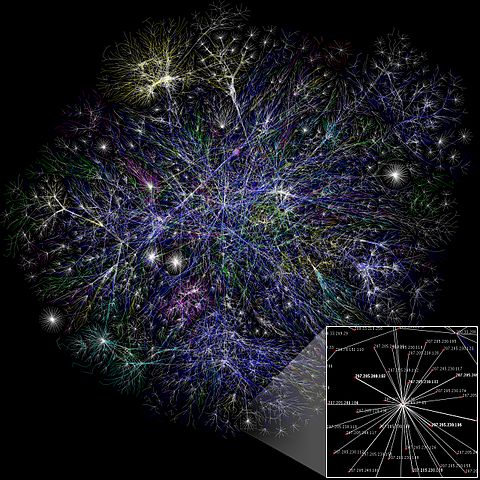

A partial map of the Internet based on 2005 data found on The Opte Project. CC BY 2.5.

Such systems are now central to our lives. Every day when we use our phones or computers we are using a distributed system within that device, where the central processing unit (CPU), memory units and input-output channels (such as the keyboard, mouse, touch screens, display screens, microphones and speakers) are all separate, communicating processes. And when we use the internet to browse the web or keep in touch by email or social media we are using a distributed system where the different processes (the web browser on my computer, the internet router, the web server) are vastly separated by distance.

This spatial separation of the processes is often the advantage of distributed systems. For example we couldn't imagine using a banking system that wasn't distributed. You can deposit your money in one place, say the bank branch on the local high street, and withdraw money from another, say from the ATM (cash machine) at the airport as you leave on your holiday.

But the complication of a distributed system, made up of events happening in different processes, says Lamport, is that "it is sometimes impossible to say that one of two events occurred first. The relation 'happened before' is therefore only a partial ordering of the events in the system." This could lead to serious consequences. It's clear that totally ordering the events in the banking system is vital, so that you can decide if a deposit occurred before a withdrawal, to make sure that people don't overdraw their accounts.

Ambiguous histories

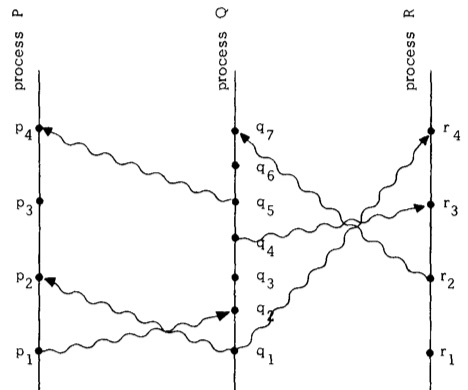

To illustrate this, consider the spacetime diagram below. (You might have heard of spacetime diagrams if you've ever studied theoretical physics, in particular, special relativity – the connection is not a coincidence and will be explained in the next article.) The horizontal direction represents space, different locations for different processes. And the vertical direction represents time – time moves up the page, later times being higher than earlier times. In these diagrams, dots denote events, vertical lines are the processes, and wave lines denote the messages between different processes.

A spacetime diagram of a distributed system made up of three processes P, Q and R.

Looking at such a diagram we see that we can say an event $a$ "happened before" an event $b$ (written $a \rightarrow b$) if we can go from $a$ to $b$ in the diagram by moving forward in time (ie, going up) along process and message lines. For example in the diagram above we can see that $p_1 \rightarrow r_4$.

It is possible in distributed systems for two events to be concurrent: for these two events $a$ and $b$ it is impossible to say that $a$ "happened before" $b$ or that $b$ "happened before" $a$. For example in the diagram above, even though the drawing suggests $r_1$ happened at an earlier time than $p_4$, we cannot know this is true as there is no direct path along process or message lines from $r_1$ to $p_4$. These two events are concurrent.

This diagram illustrates a distributed program, where the work of the program is split up amongst many different processes, each of which executes its own program, or series of events. Problems can arise if an event in one process, say one using a particular piece of data, occurs concurrently with an event in another process that modifies that piece of data. For example if you are doing a calculation with the value of some variable X in one process, while concurrently, in another process, the value of X is being modified by some other calculation.

"If this [calculation] is using a piece of data that's being modified by another process, then the abstraction of the execution of this calculation being a single event is no longer an accurate representation of what's going on," says Lamport. "There's an interaction between the innards of this atomic event and what's going on someplace else."

Such unforeseen interactions could have dire consequences, as we will find out in our next article Violating causality.

About this article

This article is part of our Stuff happens: the physics of events project, run in collaboration with FQXi. Click here to see more articles and videos about the role of events, special relativity and logical clocks in distributed computing.

Rachel Thomas is Editor of Plus. She interviewed Leslie Lamport in September 2016 at the Heidelberg Laureate Forum.