Just a little turbulence

We live in turbulent times, and not just politically. Every time we comment on the weather, make a cup of coffee, and even with every surge of blood through our beating hearts, we are affected by turbulence. And now, by studying turbulence at the smallest scale, scientists are one step closer to understanding this mysterious phenomenon.

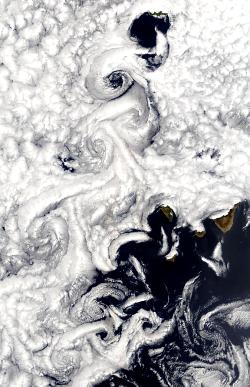

Turbulence in clouds above the Canary Islands

[Image Visible Earth, NASA]

Mathematicians describe the motion of classical fluids - including air, water and blood - using equations, such as the Navier-Stokes equations (read more about the Navier-Stokes equations in How maths can make you rich and famous: Part II from issue 25 of Plus). To tackle the complexities of turbulent flows they model the whirling vortices as very thin tornadoes or spinning lines, called stable vortex filaments. However, in the crazy quantum world of superfluids this is not a simplification - it accurately reflects what is happening. Now, in a recent issue of Nature, Finnish researcher Antti Finne and his colleagues report that they have made progress in understanding turbulence in this simpler situation. (For more on turbulence, see Understanding turbulence from Issue 1.)

Superfluids are fluids that have been cooled to a critical temperature, Tc, very close to absolute zero. At this temperature, about 2K for Helium, (-271o Celsius) some of the atoms in the fluid behave in a strange quantum-mechanical way. They no longer vibrate randomly like normal atoms, but instead behave in a coordinated manner, flowing without friction. Superfluids are thought of as a mixture of two fluids, a viscous (normal) part whose atoms behave as a classical fluid, and a frictionless (superfluid) part. At absolute zero all the mixture will be superfluid, but as the temperature rises toward the critical temperature Tc the normal proportion increases.

Mathematicians write the equations of motion for superfluids in a similar form to those for classical fluids, so that they can develop similar methods to deal with the two types of equations. For classical fluids, turbulence is governed by the Reynolds number (read more in The buzz on bumblebees from Issue 17). The Reynolds number is written as $$ Re = \frac{UL}{\nu}, $$ where $U$ is the velocity of the flow, $L$ is a measure of the size of the system, and $\nu$ is the {\em viscosity} of the fluid. The higher the Reynolds number, the greater the tendency for the flow to be turbulent.

The analogous superfluid Reynolds number, Res, looks very similar, except that it is dependent on the mass of the superfluid particle, rather than the viscosity. The big difference is that Res does not seem to completely characterise turbulence in superfluids. A superfluid can remain smooth-flowing even if Res is very large. Instead turbulence also seems to be affected by temperature, with regular flow at higher temperatures (above 0.6Tc), and turbulence at lower temperatures.

The researchers think this is caused by a "damping" effect of the viscous (normal) part of the superfluid on the frictionless (superfluid) part. The higher the temperature, the larger the normal proportion of the superfluid and the stronger the damping force counteracting any turbulence. So, as well as the external factors of size and speed that govern the move to turbulence in classical fluids via their effect on the Reynolds number, there is an internal damping factor for superfluids that also controls turbulence.

The work to understand superfluids is only just beginning. Their strange properties will no doubt lead to important applications, just as was the case for superconductors. And researchers also hope that understanding superfluid turbulence will give them new tools to tackle the more complicated classical turbulence - perhaps making the lives of weather forecasters a little less bumpy.