Plus Advent Calendar Door #17: Complex square roots

This article about complex numbers is a little advanced. See here for a basic introduction to complex numbers.

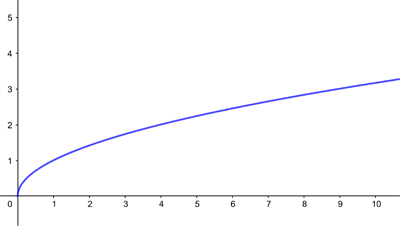

Every positive real number has two square roots, one being the negative of the other. It's easy to tell them apart by specifying whether you're looking at the positive or the negative square root. This means you can unambiguously define the square root function

$$f(x)=\sqrt{x}$$ over all the non-negative real numbers (the positive real numbers and 0).

The graph of the positive square root function defined over the non-negative real numbers.

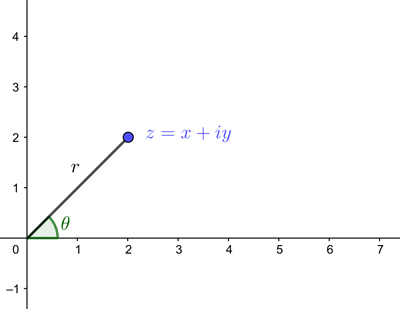

When it comes to the square root of complex numbers, things are a little tricker. Before we start, recall that according to Euler's formula a complex number $z$ can be written as $$z=re^{i\theta},$$ where $(r,\theta)$ are the polar coordinates of the point in the plane associated to $z$. Here $r$ is the distance from that point to the point $(0,0),$ and $\theta$ is the angle formed by the line connecting the point to $(0,0)$ and the positive $x$-axis (measured anti-clockwise).

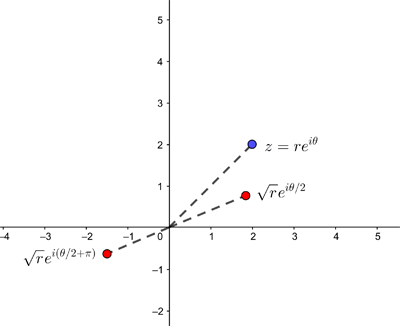

A complex number represented as a point on the plane in polar coordinates.

(See this article for more detail on Euler's formula.)

Before we carry on, we note two things. The first is that, for any positive real number $r$ and angle $\theta$, we have $$re^{i\theta}=re^{i(\theta+2\pi)}.$$

You can convince yourself that this is true by noting that the point with polar coordinates $(r,\theta)$ is the same as the point with polar coordinates $(r,\theta+2\pi)$. That's because the angle $2\pi$ corresponds to a full turn of the circle, so adding $2\pi$ to a polar angle gets you back to where you started.

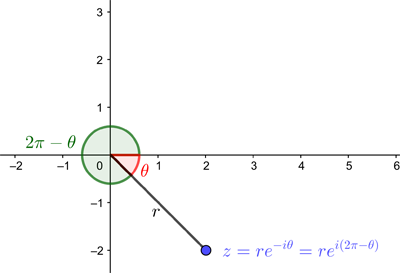

The second thing to note is that we can also say what we mean by $$re^{-i\theta},$$ where $\theta$ is positive. Since $$re^{-i\theta} = re^{i(2\pi-\theta)}$$ we can think of the complex number $re^{-i\theta}$ as represented by the point at distance $r$ from $(0,0)$, with the angle $\theta$ measured in the clockwise, rather than anti-clockwise, direction from the positive $x$-axis.

A negative angle can be interpreted as an angle measured in the clockwise direction from the positive x-axis.

Taking the square root

When it comes to the square root of a complex number $z=re^{i\theta}$ we again have two options, as we did for square roots of real numbers. The first is $$ \sqrt{r}e^{i\frac{\theta}{2}}.$$ Let's just check this works: $$\left(\sqrt{r}e^{i\frac{\theta}{2}}\right)^2=\sqrt{r}^2\left(e^{i\frac{\theta}{2}}\right)^2=re^{i\theta},$$ as required. The second option is $$\sqrt{r}e^{i(\frac{\theta}{2}+\pi)}.$$ Again let's check: $$\left(\sqrt{r}e^{i(\frac{\theta}{2}+\pi)}\right)^2=\sqrt{r}^2\left(e^{i(\frac{\theta}{2}+\pi)}\right)^2=re^{i(\theta+2\pi)}=re^{i\theta},$$ as required.

The two square roots (shown in red) for z (shown in blue).

Our two expressions, $$ \sqrt{r}e^{i\frac{\theta}{2}} \;\;\; \mbox{and}\;\;\; \sqrt{r}e^{i(\frac{\theta}{2}+\pi)}$$ are called the two branches of the square root.

Defining a function

Let's start by defining our square root function $f(z)$ on the non-negative real line. We will define the function so that for a real number $x$ on this non-negative real line, the function corresponds to the positive square root $\sqrt{x}$. This means that we need to choose the first of our two branches above, so $$f(re^{i\theta})=\sqrt{r}e^{i\frac{\theta}{2}} \;\;\;\mbox{if } \;\;\; \theta =0.$$ Let's see what happens if we extend this definition to a little sector of the complex plane which contains the non-negative real line. For example, let's define $$f(re^{i\theta})=\sqrt{r}e^{i\frac{\theta}{2}} \;\;\;\mbox{if} -0.4 \leq \theta \leq 0.4.$$ The Geogebra applet below illustrates that there is no problem with this definition. It is un-ambiguous and also gives us a continuous function: when you use the sliders to vary $r$ and $\theta$, you see that $f(z)$ (shown in red) changes continuously as $z$ (shown in blue) changes.Why can't we define our function on the whole plane in the same way? Well, consider what happens as you approach a point on the negative real line from above and from below. We can approach the point from above by looking at points $z=re^{i\theta}$ with $\theta$ increasing from $0$ to $\pi$. Since our function is $$f(z)= \sqrt{r}e^{i\frac{\theta}{2}},$$ the value of $f(z)$ approaches $$\sqrt{r}e^{i\frac{\pi}{2}}=\sqrt{r}i.$$ To approach our point from below we can look at points $z=re^{i\theta}$ with $\theta$ decreasing from $0$ to $-\pi$. Since our function is $$f(z)= \sqrt{r}e^{i\frac{\theta}{2}},$$ the value of $f(z)$ now approaches $$\sqrt{r}e^{-i\frac{\pi}{2}}=-\sqrt{r}i.$$ Therefore, if we defined our function as $$f(z)= \sqrt{r}e^{i\frac{\theta}{2}}$$ on the whole complex plane, it would not be continuous on the negative real line. As we approach a point $z$ on the negative real line from above, the function $f(z)$ approaches $\sqrt{r}i$, but as we approach $z$ from below, the function approaches $-\sqrt{r}i$. You can see this in the Geogebra applet below. Use the slider for $\theta$ to move it towards $\pi$ (to the right) and towards $-\pi$ (to the left).

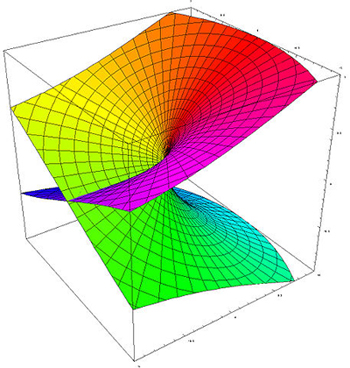

The problem of the discontinuity doesn't occur just because we chose the "wrong" branch to define our function. If we had chosen to define the function as $$f(z)= \sqrt{r}e^{i(\frac{\theta}{2}+\pi)}$$ in an analogous way, it would also have been discontinuous on the negative real line. In summary, the complex square root is a multi-valued function that can't be defined un-ambiguously on the whole complex plane in a way that makes it continuous.There is, however, a clever trick that gets us around this problem. The idea is to create a new surface on which it is possible to define a function for the complex square root in a continuous way. This so-called Riemann surface is shown below.

To find out how it is constructed, see the longer version of this article.

The Riemann surface associated to the complex square root, represented in three dimensions. A loop around the point 0 on this surface (which is right at the centre) will take you once around the top sheet and once around the bottom sheet. Figure: Jan Homann.

Return to the Plus advent calendar 2021.

This article is part of our collaboration with the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences (INI), an international research centre and our neighbour here on the University of Cambridge's maths campus. INI attracts leading mathematical scientists from all over the world, and is open to all. Visit www.newton.ac.uk to find out more.