Career interview: IT project manager

Something different

Bharat Dodia knew early that whatever he went on to do after school would involve maths. "Whenever I was asked what I wanted to do at university I would be the only one to say mathematics and be laughed out!" It didn't bother him that people thought he was strange for liking maths: "I think quite the opposite, actually. I felt quite good, I was doing something different."

After taking his O levels in 1985 at a community school in Newham in East London, he went on to do A levels in maths, further maths and physics. "It was a good combination; they were the subjects I enjoyed and maths was a discipline I wanted to follow."

The choice of A level subjects had been made solely on the basis of what he liked, but he was also aware that maths led on to good career options. "I got sound advice from my oldest brother who had a civil engineering background. He said mathematics was a good subject to study, because after doing the degree you have many choices, and it's a good grounding. I probably wouldn't have considered it for my degree otherwise, because at that age I don't think I had the maturity to think past my school education. But once I was doing my A levels I realised it really did interest me, and I should find out what happened beyond this."

Since Bharat's brother had enjoyed his time studying Civil Engineering at University College London (UCL), and Bharat also wanted to stay in the London area and live with his family while doing his degree, he chose to study at UCL too. The next question was what exactly to study. "I did wonder if I should mix mathematics with another discipline, maybe computer science or physics or management. I decided against that, because I thought that at university I should choose what interested me and that way I would achieve something. So I just did a pure maths degree."

Bharat enjoyed his degree. "Some lecturers can teach you something really complex and make it sound really easy. Then you get interested and pursue the topic yourself." In his first two years he took courses in both pure and applied maths, but from the second half of the second year he had a completely free choice of subjects, and specialised in applied maths, with modules in fluid dynamics and physics-related subjects. Even so, he is sure that maths, rather than physics, was the right choice for him. "Physics would have been too much hand-waving and experiments. I like there to be a definite answer and a definite way of doing something. A hypothesis and an experiment - that's all well and good, and it's the right way to do that kind of stuff, but it just wasn't for me. I prefer the rigour of mathematics."

Starting research

Although his path had seemed relatively clear up to that point, Bharat was not sure what he should do once he had graduated. But in a conversation with one of his lecturers about a problem that had been set for the class the topic of research came up. "He asked about my plans and if I had considered research. I said yes but that I wasn't sure in what area, and I wasn't really sure whether I would be able to come up with a genuine piece of research. I think if it hadn't been for him asking me then I probably wouldn't have pursued a career in research. You're talking about another three years of hardship and hard work with possibly no result. I felt flattered that Frank spoke to me about it, and what clinched it was he agreed to be my supervisor. If he hadn't, I'm pretty sure I wouldn't have done a PhD."

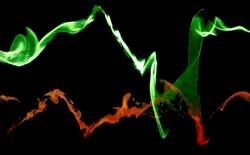

Bharat had an award from EPSRC (the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council) to study the onset of turbulence. "When a fluid, such as air, flows over an airwing, there is a transition from laminar to turbulent flow", he explains. "In that process there is a distinct phase when you get little spots of turbulence appearing, and I was researching that phase: How do those spots appear, what causes them to appear, what is their structure, how do they develop?

"As an undergraduate, you really don't have an understanding of what people do at research level. On many occasions I had a chat with the lecturers about what they're doing, but unless you're doing research yourself you will find it hard to know what they are doing. You really have no idea what open problems there are."

He graduated from UCL in 1993 with a PhD in mathematics. "I would say I probably achieved 90% of what I was after at the start. There was probably a lot more that could have been investigated, but I wanted to finish on time. But doing a PhD was a lot more fun than doing my first degree!"

Fluid dynamics in aeronautics:

the two wing-tip vortices in an aircraft's wake are

marked with different coloured dyes.

Although Bharat feels he learnt a lot from that post, he soon realised that it was not the right environment for him. "Two and a half years in I decided I had got to get out because I wasn't motivated enough. It was too much like an experiment to me, too much about the implementation. I like coming up with results rather than approximations." But he has no regrets about having dedicated so much time to pure research. "I don't think you can ever say that any research is bad research, because you do pick up life skills: How do you approach a problem, how do you solve a problem, how do you interact with others, how do you communicate, how do you explain? When I finished my PhD I did not want to leave all that."

A logical progression

Because he enjoyed coding Bharat started looking around at careers in IT and banking. He applied for a number of jobs, and was interviewed by aerospace company BAE Systems, management and IT consultancy Logica, and a small internet company. BAE Systems offered him a job, but it was in Bristol and he wasn't keen to relocate, and Logica took a very long time to consider his application. So he accepted the offer from the smaller company. "I was their all-rounder, looking after their webservers and database, coding, that kind of stuff." But it quickly became apparent that he had made the wrong choice. Fortunately, a few months later Logica got back to him with a job offer, and he decided to accept it. "In a small company every person counts, but I just wasn't happy and didn't feel like coming to work any more."

Bharat came in to Logica under their graduate recruitment scheme. The first three weeks was induction - meeting people and working on small projects. As a new recruit he had access to a central database of jobs across the whole consultancy. "You decide which jobs you're interested in, which jobs you feel comfortable with, and then you apply to the project manager."

Although he had joined the defence division, Bharat quickly realised that the internet-related skills he had picked up were of most relevance to Logica client Ford Motor Company. "I saw a project at Ford to build a daily production reporting system. At the Ford motor plants around the world they monitor daily production, and this system was required to report against the various components and parts that they build. It was about looking at cycle times and productivity - holding less stock, improving turnover and so on.

Inside one of Ford's plants

Image from Ford

Bharat worked on that project for just over a year, and then moved on to another project developing a "data warehouse" for Ford. The company use a real-time plant-floor tracking system, and Bharat was the main developer on a system to gather and efficiently store the data from that system, and generate reports to allow managers to investigate inefficiencies and potential cost savings. He worked with a business analyst and another developer, within the core business team who derived the project requirements.

Bharat sees his background in research as a strength in this sort of internal consultancy, as it has helped him to be flexible about working in a team or independently. "I think if you do research it gives you that independent element, to figure out things for yourself. I think they probably appreciated the fact that this person had a definite skillset they could use."

It's what you do, not who you are

During his career, Bharat has changed direction a couple of times - from pure research to applied research to consultancy and project management. He has heartening advice for anyone else thinking of changing direction, particularly anyone worried that their face might not fit: "What I've found is that when you're starting your career, you dive in and then realise that you've made mistakes and you have to spend time correcting things. But when you're that bit older and more experienced, you spend time upfront thinking about things and they take a lot shorter a time to do.

"I think if you've got the skillset, then whether you're young or not, whether you're a man or not, shouldn't matter."