Career interview: Project finance consultant

With a degree in astrophysics from University College London and a Masters in Applied Finance from Macquarie University, Sydney, as well as experience in consultancy and banking on both sides of the world, Nick Crawley has recently set up his own financial consultancy in Sydney, Australia. He is Managing Director of Navigator Project Finance, which provides financial modelling and analytical services to companies and investment banks seeking to put together finance for large-scale projects, such as power stations, oil rigs, toll roads and mobile telecom networks.

From a standing start

"Maths really caught my attention while I was at school," says Nick, "but not until quite late on. I was about 17 years old; I had scraped through GCSEs and was studying for A-Levels. Up till then I wouldn't even have described myself as numerate, I didn't pay attention and found school boring - there was always something else I wanted to be doing.

"It's fair to say that I didn't recognise the importance or breadth of maths - but within a year of starting to make an effort I was solving partial differential equations on my ZX Spectrum+ [an early personal computer with less computing power than current pocket calculators]."

What brought about such a dramatic change? "I signed up for two weeks work experience in the light aircraft repair and maintenance facility at the local airfield. But I actually only lasted two days - it sounded like it would be fun but in reality it was so boring! I decided right then and there that I was never going to have a job that didn't interest me, because otherwise I wouldn't do well.

"Then it struck me: to do well in school I had to find something I was interested in. I think I saw maths as an area that was the hardest thing to master. If I could crack that then I would be able to do anything: it's in physics, chemistry, statistics, geography, and with the popularity of fractals it's even in art! I felt a desire to do something really different — and decided I wanted to study astrophysics. My father, who was amazed at this idea, travelled with me to London where we visited the Physics and Astronomy Department at UCL. And that was it, I had decided — now I just had to get the grades in my exams. To help, I took on some additional courses in sixth form such as S-Level Physics and Further Mathematics."

Academia and beyond

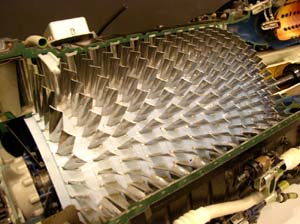

The blades of a jet engine

Nick finished his degree in Astrophysics in 1995 and then spent a year at the Jet Propulsion Laboratories in Pasadena on a research fellowship, travelling between London and California. This was an exciting time for Nick. It was a new environment, he was working with people from many different backgrounds and countries, the lab equipment was superb and, perhaps most importantly for Nick, he was no longer "being spoonfed". The work itself was stimulating and, "so much more interesting than the material covered at A level". And he was awarded research grants to work on his interests during the summer holidays, which not only meant much-appreciated income, but also gave him the opportunity to see how high-level research works.

"The area that had really grabbed my attention was the diffusion of exotic metal particles in the clouds of a particular type of star," says Nick. "The theory was explained using high order non-linear partial differential equations which, in a general sense, describe how much of the material is in the star, based upon how much of it we observe here on earth. One rainy day in my London office, I was leafing through a mountain of papers and books I had got from the library, searching for another system which was described in a similar manner but had been solved - and then I found it. The solution to the price of a European-style call option had been presented 20 years previously by Black and Scholes, who were awarded a Nobel Prize for their work. I read more about it, and the way they had found the solution had been by searching for solutions in other fields of study - they came across the Heat Diffusion Equation which gave them the break they needed to accurately price a financial contract.

Lloyds building in London

"This impressed upon me that the mathematical methods I had spent four years learning and applying in physics had a real application in the world of finance and that I probably had an advantage over students from, say, a pure economics background. So I decided to see what kinds of jobs were available and what sorts of companies were looking for people with mathematical backgrounds. I was pretty surprised to find that trading floors and structured finance departments - 'structured finance' means the provision of debt to single asset projects where the income and expenses are largely underpinned by legal and contractual structures - were all seeking to hire what they called 'rocket scientists' - people with high-level qualifications in maths and physics who work on designing financial products and modelling the stockmarket. I decided to apply for a job with the well-known accounting and consultancy firm, Ernst & Young. I was particularly drawn to the area of 'project finance' where a logical and mathematical approach is required in order to accurately forecast the cashflows of large, highly structured projects such as petrochemical refineries, power stations, mobile telecommunication networks and the like."

Nick says he has never regretted his decision to leave academia — "there's plenty of intellectual stimulation in the world of finance - the challenges that have been thrown at me, sometimes in exotic locations, have been pretty memorable! And I can't deny that as a young graduate I was attracted by the possibility of earning the amounts offered by the financial institutions."

Around the world

While working in the Ernst & Young London office, Nick was approached by the Sydney office and asked if he would like to come and establish a "financial modelling risk management" group. "They had recently realised the level of risk which they were exposing themselves to by using clients' models and also by having inexperienced staff construct complex financial models. Two weeks later I was in Sydney and the Olympics were just starting - it was a great time."

But Nick only remained with Ernst and Young for a year, after which he went over to ANZ Investment Bank as a Senior Manager. During the three and a half years he was with ANZ, Nick also decided to "formalise" his financial qualifications and took a Masters Degree in Applied Finance part-time at Macquarie University in Sydney. And once this was behind him, he felt the time was right to set up in business for himself and he now runs Navigator Project Finance Ltd. "The company is a niche consultancy which uses all the knowledge and skills I acquired over the previous 10 years of working in structured financing. We offer consultancy to both project developers and people from the investment banking and lending side. Project developers often need guidance and assistance in getting their project financing over the line and, surprisingly, investment banks often struggle to prepare financial analysis adequate to this sort of investment. We also provide training courses in financial modelling for employees of companies engaged in project finance activities."

A day a the office

A typical project on which Nick might work is the construction of a power station. Developers put together a project team in order to design and co-ordinate the financing and construction of the plant. Such a project might cost as much as $900 million and so careful planning and due diligence has to be performed before a bank will lend, say, 80% of the funds.

This analysis is where "financial modelling" comes in. Although the analysis is complicated by the fact that there are so many scenarios to be considered in order to accommodate all the possible outcomes that financiers need to consider, in fact the models can essentially be broken down into "bite-sized" pieces of maths, each of which is essentially no more complicated than the maths that's studied at A level.

The models are mostly created using Excel and Visual Basic. So much relies on a model that thousands of dollars are spent constructing it and thousands more on having the model audited by a reputable and qualified firm, usually an accountancy or actuarial firm which has a dedicated team to perform this role.

The day after "financial close" - the stage at which the financiers approve the lending of the funds - the loan is available for drawing and each party is fully committed to completing the project. This type of lending is called "nonrecourse", or "project" financing and is the way that most large projects are now financed. Such loans differ from more common loans, such as mortgages, in that there is no security. The only cash that will be available to repay the loan is that generated by the project and this is where the risk lies: if the models of costs and cashflow are wrong there are no assets to sell to get the money back. So it is in everybody's interest that the project is completed on time, and if possible early, in order to minimise the interest building up on the loan.

Hours and incentives

For Nick the most exciting thing about his job is that he is totally in control of his own destiny. "The upside is really only limited by the time I am prepared to invest in building the company, which at the moment is almost 24 hours a day! But even though the hours are phenomenal — the company is in its early stages and I probably average around 100 hours a week — I get a real buzz from the positive client feedback. It is a great feeling to hear from a mutual third party how useful our service has been for a client and how much it has benefited their business.

"Working in an investment banking environment you learn never to get too comfortable about long-term employment — it's not uncommon for banks to close departments overnight. While I was at ANZ Investment Bank the pay was good but, even after a fantastically successfully year and high share prices, bonuses were always pretty much about the same. You could argue that the pay structure was not incentive-driven enough to really drive ambitious people.

"Now it's a different story! It is virtually 100% incentive-driven and that can sometimes be a little unsettling. But commitment to quality, client satisfaction and delivering value seem to be paying dividends now. It is a low overhead environment and it would be fair enough to say that if the rest of the year is similar to the last quarter then this year's pay will be about 3 times more than at the bank."

Financial modelling, Nick says, provides an interesting combination of consultancy - to identify what the client needs - and hands-on application in order to construct the financial model itself. "After a model is built it needs to be presented and discussed with the client. Company boards often rely on the results to make big decisions so it is important they understand what has been assumed in the model and the level of accuracy achieved."

And despite the long hours and hard work, Nick has no intention of slowing down and is clear about his plans for the future. "I want to see Navigator Project Finance become the number one choice for Australasian companies who need financial modelling assistance. In parallel to this I am going to develop Navigator Project Finance into a world-class training organisation."

Watch this space.

About the author

Helen Joyce is editor of Plus.