What's the common ingredient?

Perhaps the first great challenge we encounter as we learn maths is to add fractions. Although often treated as such, adding fractions is no unique art — after all, what is addition? It is just a uniting of objects which share some common ingredient. With whole numbers the shared ingredient is the number 1. It presents itself so naturally that we do not need to search for it. For example,

$$ 3 + 6 = 3 \mbox{ lots of 1 + } 6 \mbox{ lots of 1} = (3 + 6) \mbox{ lots of 1} = 9 \mbox{ lots of 1} $$ which is shortened to $9.$ But how about fractions? Even pupils who have mastered the addition of whole numbers may find $\frac{3}{4} + \frac{2}{3}$ daunting. Mathematics may cherish symbols for their transcending of linguistic boundaries, yet by putting these compact notations into words, our sum not only takes on a more familiar look,$$ \frac{3}{4} + \frac{2}{3} = 3 \mbox{ quarters } \mbox{ + } 2 \mbox{ thirds } = 3 \mbox{ lots of 1 quarter } \mbox{ + } 2 \mbox{ lots of 1 third} %= 3 \mbox{ lots of } \frac{1}{4} \mbox{ + } 2 %\mbox{ lots of } \frac{1}{3} $$ but reveals something crucial — we are presented with \emph{different} ingredients: quarters and thirds. So how do we add them? Well, suppose we had a glass of wine and a cup of raisins — what would we have altogether? Perhaps something like, \begin{eqnarray*} 1 \mbox{ glass of wine } \mbox{ + } 1 \mbox{ cup of raisins } &= 75 \mbox{ lots of 1 grape } \mbox{ + } 120 \mbox{ lots of 1 grape } \\ &= (75 + 120) \mbox{ lots of 1 grape } \\ &= 195 \mbox{ grapes} %& = 15 \mbox{ trees.} \end{eqnarray*} because our wine and raisins are made from different amounts of the same constituent (a grape). So after the conversion, this looks just like our whole numbers example. And this is the key — we may not yet have found a common ingredient of thirds and quarters but, when we do, our example shows that (just as with whole numbers) we will be able to say something like this, \begin{displaymath} \text{1 \;\; quarter} = \lambda \mbox{ lots of $x$} \quad \mbox{ and } \quad %\end{displaymath} %\begin{displaymath} \text{ 1 \;\; third} = \mu \mbox{ lots of $x$} \end{displaymath} where $\lambda$ and $\mu$ are different amounts of the same ingredient, $x$.

Finding the common ingredient

What could that same ingredient be? First notice that, since they are equal to quarters and thirds, our $\lambda$ lots of $x$ and our $\mu$ lots of $x$ must be expressible as fractions. That is, we can write \begin{displaymath} \frac{a}{b} = \lambda \mbox{ lots of } x \quad \mbox{ and } \quad \frac{y}{z} = \mu \mbox{ lots of } x. \end{displaymath} where $a,$ $b,$ $y,$ and $z$ are whole numbers. These expressions allow us to pick our common ingredient. Say we \emph{choose} to write them as \begin{displaymath} a \mbox{ lots of } \frac{1}{b} = \lambda \mbox{ lots of } x \quad \mbox{ and } \quad y \mbox{ lots of } \frac{1}{z} = \mu \mbox{ lots of } x .\end{displaymath} By \emph{choosing} to write our equations in this way, we effectively nominate our common ingredient: we decide that $\frac{1}{b}$ and $\frac{1}{z}$ are the same. Setting $b=z$ we get \begin{displaymath} \frac{1}{4} = \frac{a}{z} \Longrightarrow z = 4a \quad \mbox{ and } \quad \frac{1}{3} = \frac{y}{z} \Longrightarrow z = 3y \end{displaymath} which shows that $z$ is a multiple of both 4 and 3. (Choice is a prominent feature of mathematics and this versatility allows us to solve some problems in many different ways. Henri Poincar\'e once even joked that "Mathematics is the art of giving the same name to different things".)Using the common ingredient

Whether it's halves or wholes: once you've found the common ingredient it's easy to add up!

respectively. So $\frac{1}{4}$ and $\frac{1}{3}$ can both be made from twelfths. Such commonality is usually described as a \emph{common denominator} (as the number beneath the horizontal line of a fraction (12 here) is its denominator). Substitution into our original sum $\frac{3}{4} + \frac{2}{3}$ (which, if you recall, we expressed as "3 lots of 1 quarter + 2 lots of 1 third") gives, \begin{eqnarray*} \frac{3}{4} + \frac{2}{3} &= 3 \mbox{ lots of 3 lots of } \frac{1}{12} \mbox{ + } 2 \mbox{ lots of 4 lots of } \frac{1}{12} \end{eqnarray*} noting that we are now adding different amounts of the same object, $\frac{1}{12}$. Simplifying further, \begin{eqnarray*} \frac{3}{4} + \frac{2}{3} &= (\mbox{3 lots of 3 + 2 lots of 4}) \mbox{ lots of } \frac{1}{12} \\ &= (\mbox{9 + 8}) \mbox{ lots of } \frac{1}{12} \\ &= \mbox{17} \mbox{ lots of } \frac{1}{12}. \end{eqnarray*}

Adding up negative numbers

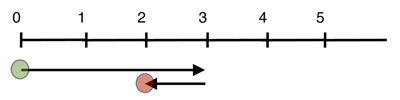

Be they whole numbers or fractions, adding objects does not differ in approach once you have found a common ingredient. Yet adding positive and negative numbers together involves no little subtlety. What is the common ingredient here? In finding it, we also discover the cause of the number line's popularity when teaching arithmetic involving different signs. All numbers with signs can be thought of as \emph{displacements}: distances with direction. A number's size gives a distance whilst its sign gives a direction. On the number line we can think of a positive number as an arrow (or, to use mathematical terminology, a \emph{vector}) pointing a distance, which is given by the value of the number, to the right and of a negative number as an arrow pointing the distance that is given by the number to the left. The plus operation then denotes a head-to-tail attachment of arrows. Their sum is equal to the arrow which begins at the tail of the first, and ends at the head of the last, arrow added. Viewing numbers in this way removes the obstacle of differing signs. For example, $$3 + (-1)$$ results in a displacement of size 2 in the positive direction, equally describable by the notation $+2$.

Although one of the most elementary lessons in our childhood, addition possesses a certain richness. We can bask in the knowledge that adding up is the single step that began this great journey into the modern world.

About the authors

Andrew Irving

Andrew Irving received his PhD in applied mathematics from the University of Manchester, where his research focused on analytical techniques for biological networks. His current research interests also include Markov processes and collective behaviours. He also enjoys playing guitar and writing his own songs.

Ebrahim Patel

Ebrahim Patel is a postdoctoral researcher in the Mathematical Institute at the University of Oxford. He is interested in a variety of things, including discrete dynamical systems, max-plus algebra, Premier League footballer analysis and complex systems in general.

"Aerodynamically, the bumble bee shouldn't be able to fly, but the bumble bee doesn't know it so it goes on flying anyway." (Mary Kay Ash)