Imagine a cake. Now imagine cutting the cake in half. Then imagine cutting a half into quarters. Then a quarter into eighths, an eighth into sixteenths, and so on, forever. What can we say about the sizes of the pieces of cake as we keep cutting?

One thing we can say is that the pieces get smaller and smaller. By keeping cutting you can make the pieces thinner than the width of a human hair, or smaller than the tiniest atom (in theory at least, in practice it's a bit hard to do). In fact, you can make those pieces arbitrarily thin.

What we have here is an intuitive example of a sequence converging to a limit. The sequence in this case consists of the numbers

$$1, 1/2, 1/4, 1/8, 1/16, ...$$

which represent the sizes of the pieces of cake as you keep cutting. The limit in this case is the number $0$. The numbers in the sequence get progressively closer to $0$, and they eventually become arbitrarily close to $0$. No matter how small a number you give me, I can show you a point along the sequence so that all numbers beyond this point are smaller than the number you gave me.

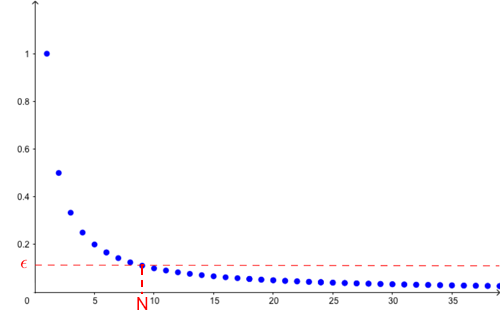

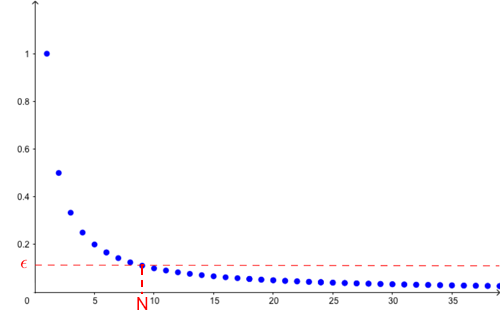

A visualisation of our sequence. The horizontal axis measures how far down the sequence we are and the vertical axis shows the size of the corresponding number in the sequence.

To put this into general mathematical language, let

$$a_0, a_1, a_2, a_3, ....$$

represent a sequence of real numbers. Then this sequence is said to converge to the limit $0$ if given any real number $\epsilon$ greater than $0$ there's a positive integer $N$ such that for all $n$ greater than $N$, the number $a_n$ in the sequence is smaller than $\epsilon$. (The symbol $\epsilon$ here stands for the Greek letter epsilon.) A sequence converging to 0 is also often written as

$$\lim_{n \to \infty} \{a_n\} = 0.$$

Sequences can also have other numbers as their limit, not just $0$. An example is the sequence

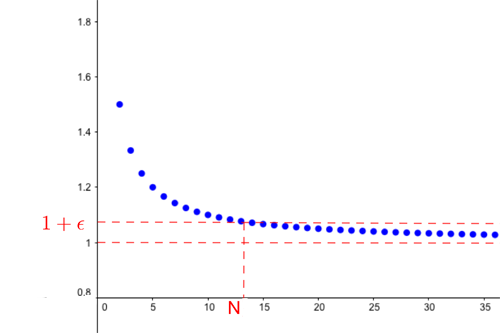

$$3/2, 5/4, 9/8, 17/16...,$$ which you get from our original cake sequence above by adding $1$ to each number. In this case the limit of the sequence is $1$ because the numbers in the sequence get closer and closer to $1$, in fact they come arbitrarily close to $1$ if you move sufficiently far down the sequence.

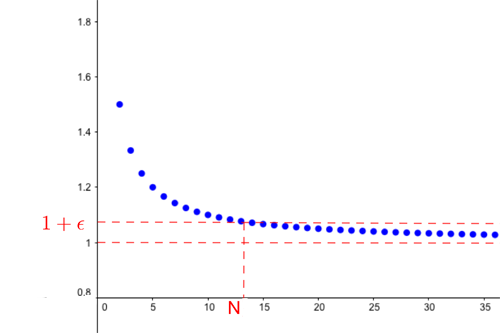

A visualisation of our new sequence. The horizontal axis measures how far down the sequence we are and the vertical axis shows the size of the corresponding number in the sequence.

In general mathematical language, if

$$a_0, a_1, a_2, a_3, ....$$

is a sequence of real numbers, then this sequence is said to converge to the limit $L$ (where $L$ is a real number) if given any real number $\epsilon$ greater than $0$ there's a positive integer $N$ such that for all $n$ greater than $N$, the number $a_n$ in the sequence lies within a distance $\epsilon$ of $L$. A sequence converging to the limit $L$ is also often written as

$$\lim_{n \to \infty} \{a_n\} = L.$$

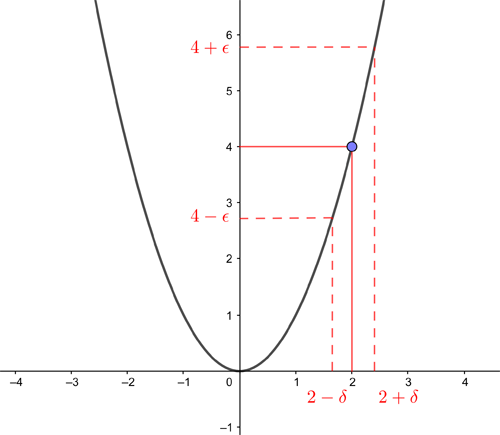

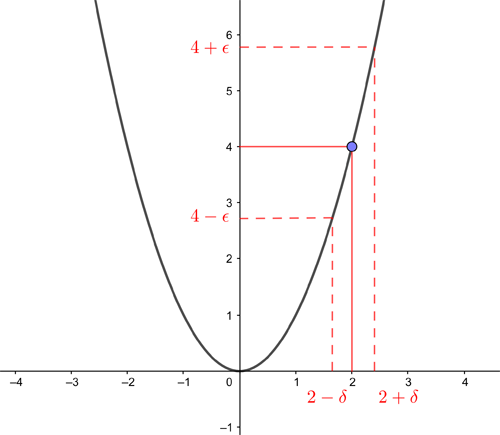

This defines the limit of a sequence of numbers. You can also define the limit of a mathematical function, such as $$f(x)=x^2,$$ as the variable $x$ tends to some special value $x_0$. The function \emph{converges} to the limit $y_0$ as $x$ tends to $x_0$ if the value of $f(x)$ gets closer and closer, arbitrarily close to, the number $y_0$. For example, as $x$ tends to $x_0=2$, the function $$f(x)=x^2$$ converges to the limit $y_0=4.$

In formal mathematical language, we say that the function $f(x)$ converges to the limit $y_0$ as $x$ tends to $x_0$ if given any positive real number $\epsilon$ there is a positive real number $\delta$ so that whenever $x$ is within a distance $\delta$ of $x_0$, $f(x)$ is within a distance of $\epsilon$ of $y_0$. (Here the symbol $\delta$ stands for the Greek letter delta.)

The graph of f(x)=x2. As long as x is within δ of 2, f(x) lies within ε of 4.

A function converging to the limit $y_0$ as $x$ tends to $x_0$ is also often written as

$$\lim_{x \to x_0} f(x) = y_0.$$

The concept of a limit lies at the heart of calculus, which you can read about

here.

"It is a truth universally acknowledged that $\epsilon$ is always a very small number."

Return to the Plus advent calendar 2022.

This article is part of our collaboration with the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences (INI), an international research centre and our neighbour here on the University of Cambridge's maths campus. INI attracts leading mathematical scientists from all over the world, and is open to all. Visit www.newton.ac.uk to find out more.