Maths goes to the movies

Got your popcorn? Picked a good seat? Are you sitting comfortably? Then let the credits roll...

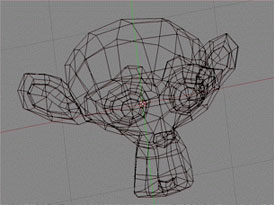

First objects are modelled as wire skeletons made up from simple polygons such as triangles.

We have all marvelled at the incredibly life-like computer generated images in the movies. What most of us don't realise is that the animals of The Jungle Book and most of the action in super hero films — particularly the star turn of the Incredible Hulk — would not have been possible without mathematics.

But how are these amazing images made? Computer graphics and computer vision are huge subjects. But one particular piece of maths you might learn towards the end of school is key to making the magic happen.

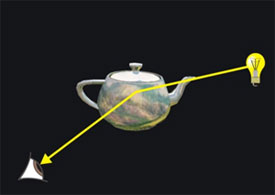

Trace a ray from your viewpoint to a facet. Does it reflect off and intersect a light source?

The first step in creating a computer generated movie is to create the characters in the story and the world they live in. Each of these objects is modelled as a surface made up of connected polygons (usually triangles). The coners of each triangle is stored as a point in three-dimensional space in the computer memory. Then this surface is realistically shaded to mimic real light, using another mathematical method called ray tracing. (You can read more here and here.)

All it takes is a little imagination

Once our scene is set, and lit, we are still waiting for the director to shout "Action!" and our characters to start moving. And here is where maths brings our images to life.

One of the most basic ways an object can move is to rotate around a given axis and through a given angle. And this movement is made simple by using complex numbers: those numbers that involve the number $i$, where $i^2=-1$.

In particular, we need the geometric interpretation of complex numbers where they are associated with points in the two-dimensional plane, with the real number $1$ sitting on one axis, and the imaginary number $i$ sitting on the other. For example the number $1+i$ corresponds to the point (1,1). Generally, a complex number $a + ib$ corresponds to the point (a,b).

Multiplication by complex numbers has a geometric description — rotation.

Let's look at what happens if we multiply $1+i$, represented by the point (1,1) by $i:$ $$ i(1+i)=i-1=-1+i $$ which is represented by the point (-1,1). But the point (-1,1) is what you get when you rotate the point (1,1) around the point (0,0) by 90 degrees. Multiplying by $i$ again gives : $$ i(-1+i)=-i-1=-1-i, $$ which is the point (-1,-1), a rotation of 90 degrees again. Multiplying by $i$ is an instruction to rotate by 90 degrees! In fact, any rotation, not only the 90 degree one, can be achieved using multiplication by a complex number.

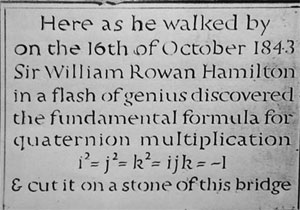

The commemorative plaque now on Broome Bridge, under which Hamilton was walking when he discovered quaternions.

Moving to 3D

The wire frames of our characters, however, are stored as a collection of points in three-dimensional space. The person who gave us a way of rotating things in three dimensions is the mathematician Sir William Rowan Hamilton, perhaps Trinity College Dublin's most famous son. He devoted the last two decades of his life to searching for a way to represent three-dimensional rotations in a similar manner as complex numbers can represent rotations in two dimensions.

Hamilton's flash of brilliance, as he walked under Broome Bridge in Dublin, was something he called quaternions. It turns out that quaternions are the most efficient way to rotate objects in three dimensions. But not everyone was happy with his new method of multiplication. Lord Kelvin, the physicist, said of quaternions: "... though beautifully ingenious, [they] have been an unmixed evil to those who have touched them in any way!"

If you've ever stayed on after a movie to watch the entire credits roll you'll be aware that a huge variety of creative talent goes into making a successful movie: writers, directors, actors, costume designers, prop builders... the list goes on. But one word is often missed off that credit list — mathematics. Many of today's movies wouldn't be possible without the geometry of ray tracing or quaternions spinning objects in space. So the next time you settle into your cinema seat to enjoy a CG spectacle, raise your popcorn to mathematics, the hidden star of the show.

This is an edited version of Joan Lasenby's article Maths goes to the movies. You can read the full article here.

You can find out more about complex numbers and things you can do with them in this introductory package and in our teacher package.