'Please, Mr Einstein'

Please, Mr Einstein

by Jean-Claude Carrière

An unnamed girl in an unnamed, but contemporary, European city enters a rather gloomy old building, reading its address from a crumpled piece of paper. Inside, being given preference over a dozen people sitting in a waiting room, she is ushered into the office of Albert Einstein. "You said that time doesn't exist, so I took the liberty of coming to see you," she says. "You did the right thing," he replies. Thus a conversation ensues that spans all the 176 pages of this book.

This simple but imaginative set-up seems ingenious at first. What better way to explore Einstein's life and work than through the questions of a girl who is intelligent but, like the readers this book is intended for, largely ignorant of the subject? And as far as the feel of the book is concerned, this device does indeed work very well. The dreamy and gentle tone has none of the dryness that so easily creeps into science books and biographies, and you never get the feeling that the author had to fight the urge to put in an equation. This, maybe, is not surprising, given that Carrière is not a scientist but a screenwriter and actor, famous for his screenplays of Luis Buñuel's Belle de Jour and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. Like the intended audience, he comes to the subject as an outsider, and describes it with an outsider's awe that in many places is infectious.

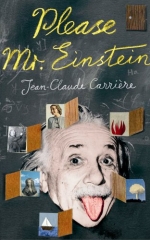

Unfortunately, though, the setting proves quite limiting in other ways. Having words on his work and personal life placed into his mouth by someone else, in my view, reduces Einstein to the two dimensions of the page. The man I met in this book hardly grows beyond the Einstein of the popular imagination, represented by the all-too-famous image adorning the cover of the book. Carrière does focus on intriguing aspects of Einstein's personal life — his feelings about his involvement with the nuclear bomb and about his superstar status, for example — and given the scope of the book, we can't expect him to go into any more depth than he does. But seeing Einstein himself paint his thoughts and feelings with this rather broad brush left me unconvinced. The Einstein of the book remains Carrière's mouth piece, a card board cut-out, and I could not help wondering what Einstein himself would have thought of this.

A case in point, in this context, is a passage which sees Einstein meeting Newton. Compared to Einstein's two dimensions, poor Newton shrinks to a mere point. Stubbornly and foolishly hanging on to his theory of gravitation and his notion of god, he is nothing more than a caricature, used to make a point about the breaking of mind sets. If you don't know much about the subject, you may emerge from reading this passage thinking that Newtonian gravitation has been rendered utterly useless by Einstein' theory, when in reality it still dominates the physics of the world we experience, that is the physics of everything that is not minutely small or extremely large. Newton's other great invention, the calculus, hardly gets a mention. Artistic license does of course apply, and the fictitious setting absolves Carrière from having to be dead accurate. But still, I found this one-dimensional characterisation disappointing.

As the conversation between Einstein and the girl unfolds, it periodically touches on the actual physics. There are a number of text book examples, the free-falling elevator is one, and Carrière, through Einstein, spends a lot of time explaining the easier concepts without making too much headway on the harder ones. But this is to be expected: the book tries to engage readers who normally would not venture into this territory, and it probably does so quite well. The fuzzy knowledge you will emerge with from reading the book is a lot more than no knowledge at all.

What this book does really well is describe the wonder and mystery that motivates science, which in turn opens doors to worlds even more wondrous and mysterious than the one we can perceive. While mind-boggling concepts, such as multiple universes, are never explored in any depth, there is a clear sense of the breathtaking territory that theoretical physics can take you into, if you are willing to follow. Carrière gently touches on questions about the limits of human knowledge, our paradoxical state of simultaneously being extremely limited and able to transcend our limitations, and the conflict between age-old wisdom and modern science. There is no deep analysis, just a slightly opened door and lots of material from which to spin your own thoughts.

Please, Mr Einstein could be subtitled "Einstein for the lazy or slightly unwilling". What you will not get from reading this book is a more than skin-deep understanding of Einstein the person, or of his work. What you will get is an entertaining and pleasant read, a gentle introduction to the subject that never strays into deep waters, and a lot of ideas to ponder. And, should you need it, a good dose of motivation to learn more.

- Book details:

- Please, Mr Einstein

- Jean-Claude Carrière

- hardback - 176 pages (2006)

- Harvill Secker

- ISBN: 1843433044

Marianne Freiberger is co-editor of Plus