The ten dimensions of string theory

In the latest poll of our Science fiction, science fact project you told us that you wanted to know how many dimensions there are. Here is the second part of theoretical physicist David Berman's answer (you can read the first part here). Click here to see other articles exploring this question and here to listen to our interview with Berman as a podcast.

Solving string theory

For 60 years the Kaluza-Klein Theory of extra spatial dimensions that we explored in the previous article existed only as a mathematical oddity. However in the 1980s it came of age. String theory, the idea that the fundamental building blocks of nature are string-like rather than point-like, had been around since the late 1960s. (You can read more about string theory in String theory: from Newton to Einstein and beyond.) Then physicists realised that string theory could provide something that had so far eluded them: a single theory that combines the physics of the very smallest and very largest scales, known as quantum gravity.

A string universe. Image © R. Dijkgraaf.

But string theory has one very unique consequence that no other theory of physics before has had: it predicts the number of dimensions of spacetime. For the mathematics of string theory to be consistent, the number of dimensions of spacetime must be 10.

Initially people took this to be a criticism of string theory. If it predicts 10 dimensions and you look around and only see four (three spatial dimensions and one time dimensions) then you might ask: "Where are the other six dimensions?" But Kaluza and Klein had solved that problem 60 years earlier: they rolled the other dimensions up.

Looking for extra dimensions

This is all very interesting theoretically but can we ever hope to have proof that these other dimensions exist? To understand how you can observe extra dimensions consider the following two laws. The gravitational force between two massive bodies is:

![\[ F=\frac{GMm}{r^2} \]](/MI/d17a860d0920badefb6bd6c41171617e/images/img-0001.png) |

is the gravitational constant,

is the gravitational constant,  and

and  are the masses of the two bodies and

are the masses of the two bodies and  is the distance between them. The electrostatic force between two charges is:

is the distance between them. The electrostatic force between two charges is: ![\[ F=\frac{k_ e q_1 q_2}{r^2} \]](/MI/d17a860d0920badefb6bd6c41171617e/images/img-0006.png) |

is Coulomb's constant,

is Coulomb's constant,  and

and  are the charges and

are the charges and  is the distance between them. What do you notice about both of these laws? Both of these forces follow the inverse square law: the magnitude of the force is proportional to

is the distance between them. What do you notice about both of these laws? Both of these forces follow the inverse square law: the magnitude of the force is proportional to  , the inverse of the distance squared.

, the inverse of the distance squared.

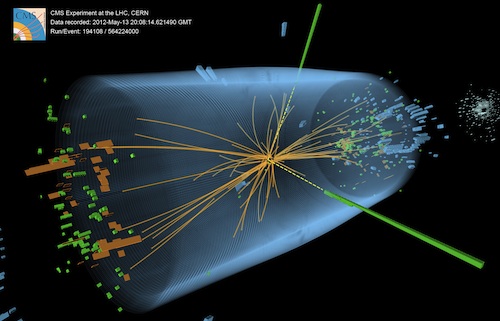

Looking for signatures of extra dimensions at the LHC (Image © CERN)

This  relationship is tied to there being three spatial dimensions. If you are in

relationship is tied to there being three spatial dimensions. If you are in  spatial dimensions then these forces between two objects are proportional to

spatial dimensions then these forces between two objects are proportional to  . So in three space dimensions forces are proportional to

. So in three space dimensions forces are proportional to ; in the nine space dimensions of string theory they're proportional to

; in the nine space dimensions of string theory they're proportional to  .

.

Physicists look for deviances from the inverse square law when they are looking for evidence of extra dimensions. It's very hard to do these sorts of experiments, however, as to observe any deviations you need to conduct them at distances which are incredibly small. Suppose we do have nine spatial dimensions and some of those dimensions are curled up. If you're working at distances that are much bigger than the curled up dimensions then the law looks like  . And when you're working at distances that are much smaller than the curled up dimensions the law looks like

. And when you're working at distances that are much smaller than the curled up dimensions the law looks like  . The principal forces will change as you reduce experimental distances and the transition occurs at distances the size of the curled dimensions. So in principle we could observe these extra dimensions but in practice is depends on how small the dimensions really are.

. The principal forces will change as you reduce experimental distances and the transition occurs at distances the size of the curled dimensions. So in principle we could observe these extra dimensions but in practice is depends on how small the dimensions really are.

This is one of the signatures of extra dimensions that physicists are looking for at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). But if they don't find this evidence it doesn't mean that these extra dimensions don't exist. That would be like physicists in the 1990s saying that as LEP (the previous collider before the LHC) hadn't found the Higgs particle that it didn't exist. It took the next generation of colliders, the LHC, to finally find evidence for the Higgs. Experimentalists are clever! If they don't find evidence of extra dimensions using colliders such as the LHC, they'll come up with something else, such as experiments using cosmic rays which have much higher energies that may have the capacity to discover these extra dimensions.

They found it! An event recorded by the CMS detector in 2012 showing the characteristics expected from a Higgs boson decaying into two photons. (Image CMS)

Progress and patience

As we progress in science (and physics is the oldest science) the time scales between theoretical prediction and experimental discovery are going to get quite long. Roughly 50 years ago Peter Higgs first thought of the Higgs particle, and now they have found it using the LHC. It might take just as long to find evidence for extra dimensions. I think taking 50 years to find something as profound as extra dimensions is neither here nor there when you consider humanity has only been messing around with experiments for a few thousand years. We've made remarkable progress.

Being aware that we live in more dimensions than we see is a great prediction of theoretical physics and also something quite profound. Physics tells us again and again that how we perceive nature as a human being is not how nature is. Extra dimensions would be one of the most striking examples of this. Your brains are used to working in three spatial dimensions, we have trouble imagining four spatial dimensions, and can't get close to picturing any more dimensions than that. And yet mathematically we can imagine many dimensional space. And the fact that that might be realised in nature is a profound thing.

About the author

David Berman is a Reader in Theoretical Physics at Queen Mary, University of London. He previously spent time at the universities of Manchester, Brussels, Durham, Utrecht, Groningen, Jerusalem and Cambridge as well as a year at CERN in Geneva.

His interests outside of physics include football, music and theatre and the arts.