When things get weird with infinite sums

Things can get weird when we deal with infinity. Consider the following sum

![\[ S = 1-1+1-1+1-1+1-1+ ... \]](/MI/47592994e280fd36129f2ac47cb70aa8/images/img-0001.png) |

It’s called Grandi’s series, after Italian mathematician, philosopher, and priest Guido Grandi (1671-1742).

If we group its terms this way

![\[ S = (1-1) + (1-1) + (1-1) + (1-1) + ... \]](/MI/47592994e280fd36129f2ac47cb70aa8/images/img-0002.png) |

it’s easy to see that  should be equal to

should be equal to  because each individual bracket is equal to

because each individual bracket is equal to  Nothing stops us, however, from grouping its terms in a different way, for example

Nothing stops us, however, from grouping its terms in a different way, for example

![\[ S = 1 + (-1+1) + (-1+1) + (-1+1) + ..., \]](/MI/47592994e280fd36129f2ac47cb70aa8/images/img-0006.png) |

in which case  should be equal to

should be equal to  ! There is even a third way of evaluating this sum. Say that we rewrite it as

! There is even a third way of evaluating this sum. Say that we rewrite it as

![\[ S = 0+1-1+1-1+1-1+... \]](/MI/47592994e280fd36129f2ac47cb70aa8/images/img-0008.png) |

Guido Grandi (1671-1742).

All we did was to add a zero at the start so I hope we can agree that we haven’t changed the sum at all. If we now write  twice

twice

![\[ S = 1-1+1-1+1-1+1-1+ ... \]](/MI/69430934242aa8b6f67b4ed77b98a7e9/images/img-0002.png) |

![\[ S = 0+1-1+1-1+1-1+1- ... \]](/MI/69430934242aa8b6f67b4ed77b98a7e9/images/img-0003.png) |

and add them together we get

![\[ S+S = 2S = (1+0)+(-1+1)+(1-1)+(-1+1)+... \]](/MI/69430934242aa8b6f67b4ed77b98a7e9/images/img-0004.png) |

Hence  should be equal to

should be equal to  which gives that

which gives that  should be equal to

should be equal to

Infinite but tame

As you can see, sums containing an infinite number of terms, known as infinite series, can challenge our understanding of very basic mathematical concepts such as addition and subtraction. Our next stop in our exploration of infinite series is the following geometric series:

![\[ S = \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{8} + \frac{1}{16} + ... \]](/MI/94457f264148c154d17754cae838269a/images/img-0001.png) |

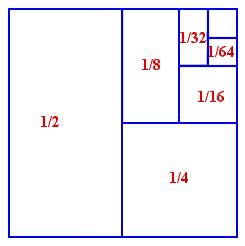

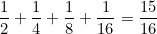

There's a clever way of figuring out the value of this sum, using the diagram below

Take a square of side length  and it divide it in half to get two rectangles, which both have area

and it divide it in half to get two rectangles, which both have area  Now divide one of those rectangles in half as shown, to get two squares of area

Now divide one of those rectangles in half as shown, to get two squares of area  Divide one of those squares in half to get two rectangles of area

Divide one of those squares in half to get two rectangles of area  and so on, ad infinitum. The total area (of the squares and rectangles we left undivided) is the same as the sum of all terms of the geometric series. Since that area is just the area of the large square, the geometric series appears to be equal to

and so on, ad infinitum. The total area (of the squares and rectangles we left undivided) is the same as the sum of all terms of the geometric series. Since that area is just the area of the large square, the geometric series appears to be equal to

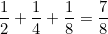

And indeed, mathematicians agree with this statement. They say that the series converges to  Formally convergence is defined by looking at the sequence of partial sums:

Formally convergence is defined by looking at the sequence of partial sums:

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

and so on.

The partial sums gives us a sequence of numbers,  which get closer and closer to

which get closer and closer to  in fact they get arbitrarily close to

in fact they get arbitrarily close to  as we include more and more terms. In general, when the sequence of partial sums of an infinite series converges on some limit number

as we include more and more terms. In general, when the sequence of partial sums of an infinite series converges on some limit number  in this way, then we say that the infinite series converges to

in this way, then we say that the infinite series converges to

Notice that this doesn’t happen for the Grandi’s series above. The partial sums are

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

and so on. The partial sums eternally skip from 1 to 0 and back again. They don’t converge to a limiting value, so there’s no obvious way of assigning a value to the series.

Infinite and divergent

It seems fairly intuitive that the geometric series above should converge to 1. The individual terms of the series,  and so on get smaller and smaller. So although we are constantly adding things to make the sum bigger and bigger, the amount we are adding eventually becomes so small, it’s no surprise we never exceed 1. This argument however is flawed. Let’s take a look at the harmonic series:

and so on get smaller and smaller. So although we are constantly adding things to make the sum bigger and bigger, the amount we are adding eventually becomes so small, it’s no surprise we never exceed 1. This argument however is flawed. Let’s take a look at the harmonic series:

![\[ S = 1 + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{5} + ... \]](/MI/f7089cf704ba12610e716e1d8513c4b8/images/img-0002.png) |

Similarly to the geometric series we investigated above, the terms of the harmonic series get smaller and smaller. But surprisingly the harmonic series diverges: the terms in the sequence of partial sums get bigger and bigger, eventually exceeding all bounds. We say that the series tends to infinity.

The harmonic series diverges

If this sounds hard to believe, here is a proof by contradiction of the divergence of the harmonic series. In a proof by contradiction we start by assuming that the opposite of what we are trying to prove is true and then show that this leads to a contradiction. If we are trying to prove statement  is true, then we start by assuming the opposite: that not

is true, then we start by assuming the opposite: that not  is true. If this assumption leads to a contradiction, then this implies that the not

is true. If this assumption leads to a contradiction, then this implies that the not  must be false, so our original statement

must be false, so our original statement  must be true. In this case, we want to show that the harmonic series diverges, so we assume that the harmonic series converges to some positive value

must be true. In this case, we want to show that the harmonic series diverges, so we assume that the harmonic series converges to some positive value

We know that

![\[ \frac{1}{3}>\frac{1}{4}, \]](/MI/a06d3b17e8827cc1d06decc2876ea652/images/img-0003.png) |

![\[ \frac{1}{5}>\frac{1}{6}, \]](/MI/a06d3b17e8827cc1d06decc2876ea652/images/img-0004.png) |

![\[ \frac{1}{7}>\frac{1}{8}, \]](/MI/a06d3b17e8827cc1d06decc2876ea652/images/img-0005.png) |

and so on. So if we replace the fractions with odd denominators by their consecutive even ones we find the following inequality

![\[ H = 1+\frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{5} + \frac{1}{6}+\frac{1}{7} +\frac{1}{8}+ ... > 1+\frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{6} + \frac{1}{6}+\frac{1}{8} +\frac{1}{8}+ ... \]](/MI/a06d3b17e8827cc1d06decc2876ea652/images/img-0006.png) |

If we now combine the fractions with the same denominator we get

![\[ H = 1+\frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{5} + \frac{1}{6}+\frac{1}{7} +\frac{1}{8}+ ... > 1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{4}+... \]](/MI/a06d3b17e8827cc1d06decc2876ea652/images/img-0007.png) |

On the right-hand side the harmonic series appears again, plus an extra term of  This proves that

This proves that

![\[ H > H+\frac{1}{2}! \]](/MI/a06d3b17e8827cc1d06decc2876ea652/images/img-0009.png) |

As this contradiction followed from our assumption that the harmonic series converges, we can conclude that this assumption is false: the harmonic series does not converge. As the partial sums get larger and larger by smaller and smaller increments (we add a term of the form  at every step) the only other possibility is that the sequence of partial sums grows beyond all bounds (rather than skipping around akin to Grandi’s series). This proves that

at every step) the only other possibility is that the sequence of partial sums grows beyond all bounds (rather than skipping around akin to Grandi’s series). This proves that  diverges.

diverges.

Infinite and bizarre

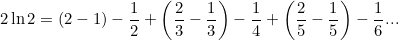

Things get seriously bizarre when we examine the alternating harmonic series. Built from the harmonic series but with every other term negative, the alternating harmonic series is defined as follows:

![\[ S = 1 - \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} - \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{5} - ... \]](/MI/81d722878d7629eedb2ec6f1d6a8604b/images/img-0001.png) |

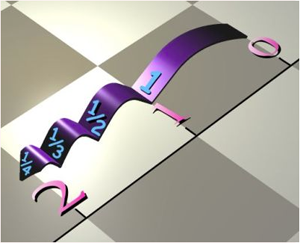

The mathematician Bernard Riemann (1826-1866) proved an important result about rearrangements of infinite series.

It’s possible to show that the alternating harmonic series converges to  (here

(here  stands for the natural logarithm of

stands for the natural logarithm of  ). You can verify this using a calculator or, if you’re advanced in your calculus, using the Taylor series of

). You can verify this using a calculator or, if you’re advanced in your calculus, using the Taylor series of  evaluated at

evaluated at

So let’s start with this fact, writing

![\[ \ln {2} = 1 - \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} - \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{5} - ... \]](/MI/d3fe9b7d6cf8effd7f717a5f23dd30ff/images/img-0006.png) |

Now let’s multiply through by

![\[ 2\ln {2} = 2 - \frac{2}{2} + \frac{2}{3} - \frac{2}{4} + \frac{2}{5} - \frac{2}{6}+\frac{2}{7} - \frac{2}{8}... \]](/MI/d3fe9b7d6cf8effd7f717a5f23dd30ff/images/img-0007.png) |

If we now simplify the fractions so that all fractions with the even denominators are reduced and then combine the terms with the same denominator – and you can see that only fractions with odd denominators will be combined – we get

|

(1) |

Removing the brackets we have

![\[ 2\ln {2} = 1 - \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} - \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{5} - ... \]](/MI/b6ec8bdd84fdc6c38b12e493360aab0b/images/img-0002.png) |

The right-hand side is the alternating harmonic series, so we seem to have proved that

![\[ 2\ln {2} =\ln {2} \]](/MI/b6ec8bdd84fdc6c38b12e493360aab0b/images/img-0003.png) |

But, hang on, what? There must be a mistake in our working. I find it hard to believe, but in fact there is nothing wrong with our working. The paradox is explained by the fact that, when we rearrange the terms of the alternating harmonic series, the series converges to a different value. The right-hand side of expression (1) above can be written as

![\[ 2\ln {2} = (2 - 1) - \frac{1}{2} + \left( \frac{2}{3} - \frac{1}{3} \right) - \frac{1}{4} + \left(\frac{2}{5} - \frac{1}{5}\right) - \frac{1}{6} ... = 2\left(1 - \frac{1}{2} - \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{3} - \frac{1}{6} - \frac{1}{8} + \frac{1}{5} ... \right). \]](/MI/b6ec8bdd84fdc6c38b12e493360aab0b/images/img-0004.png) |

The problem comes from the fact that while

![\[ 1 - \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} - \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{5} - ... \]](/MI/b6ec8bdd84fdc6c38b12e493360aab0b/images/img-0005.png) |

converges to  the rearranged series

the rearranged series

![\[ 1 - \frac{1}{2} - \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{3} - \frac{1}{6} - \frac{1}{8} + \frac{1}{5} ... \]](/MI/b6ec8bdd84fdc6c38b12e493360aab0b/images/img-0007.png) |

converges to

![\[ \ln {2}+\frac{1}{2}\ln {\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)}, \]](/MI/b6ec8bdd84fdc6c38b12e493360aab0b/images/img-0008.png) |

despite the fact the two series have exactly the same terms!

Let’s see if we can make sense of this. In the classic formulation of the alternating harmonic series we start with  and subtract

and subtract  , then add

, then add  and subtract

and subtract  and so on. For each added term we subtract exactly one term. In the second formulation of the alternating harmonic series, we subtract two terms for each term that we add. What do you think will happen?

and so on. For each added term we subtract exactly one term. In the second formulation of the alternating harmonic series, we subtract two terms for each term that we add. What do you think will happen?

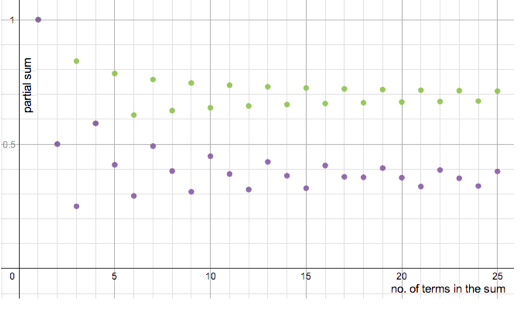

The graph below shows what happens to the partial sums as we add terms one at a time. It shows the first 25 partial sums. The green dots are the partial sums for the classic alternating harmonic series and the purple dots are the partial sums for our rearrangement of the series. The graph shows that the two series will converge to different values.

It turns out that by rearranging the alternating harmonic series we can make it converge to any value we like. Try to work out for yourself what value

![\[ S = 1 + \frac{1}{3} - \frac{1}{2}+ \frac{1}{5}+ \frac{1}{7} - \frac{1}{4}+ \frac{1}{9}+ \frac{1}{11}-\frac{1}{6}+ ... \]](/MI/670413acfac23b394453e5936aed09ec/images/img-0001.png) |

converges to. See here for an answer.

You will be glad to know that, for a series with only positive terms, altering the order of the terms does not affect the sum.

To read more about infinite series see An infinite series of surprises.

About the author

Luciano Rila works in the Department of Mathematics at University College London and is also an Area Coordinator for the Further Maths Support Programme. He is keen to promote the beauty of mathematics to young mathematicians and the general public. He also teaches static trapeze. You can follow him on Twitter @DrTrapezio