The element of surprise in mathematics

Why do so many people say they hate mathematics?

All too often, the real truth is that they have never been allowed anywhere near it, and I believe that mathematicians like myself could do more, if we wanted, to bring some of the ideas and pleasures of our subject to a wide public.

And one way of doing this might be to emphasise the element of surprise that often accompanies mathematics at its best.

Everybody likes a nice surprise.

A trick with numbers

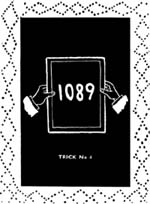

I had my first mathematical surprise in 1956, at the age of 10. I was keen on magic tricks at the time, and one day I came across a "trick with numbers" in an article called "Abracadabra! Uncle Jack turns you into a Conjuror!"

Professional mathematicians, of course, regard this "1089 trick" as mathematically lightweight and of relatively little consequence. But I have to tell you this: if you first see it as a 10-year old boy in 1956, it blows your socks off.

Surprising geometry

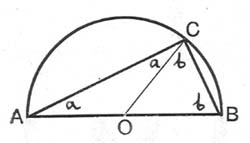

A little later on I had my first surprise in geometry. One day at school we were told that if AB is a diameter of a circle, and C is any point on the circumference, then the angle ACB is a right angle. I remember finding this difficult to believe at the time; it seemed to me that moving the point C along the circumference would almost certainly change the angle ACB, especially as C moved closer and closer to B.

But it doesn't.

OA=OB=OC.

So triangle AOC is isosceles, and the two angles marked a in the diagram are therefore equal. By the same argument applied to the triangle BOC, the angles marked b are also equal. But the angles of the triangle ACB add up to 180o, so

a+(a+b)+b=180o.

So a+b=90o, and angle ACB is therefore a right angle.

Even now, I still regard this as one of the most devastatingly effective and illuminating proofs in the whole of mathematics.

Surprising mistakes

The great mathematician Leonhard Euler

In 1753, for instance, the great Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler proved the N=3 case of Fermat's Last Theorem. He proved, in other words, that there are no whole number solutions a, b, c to the equation:

a3 + b3= c3.

In short, 2 cubes cannot add up to a cube.

But a little later he went on to conjecture that, in a similar way, it would be impossible for 3 fourth powers to add up to a fourth power, and, more generally, that it would be impossible for m-1 mth powers to add up to an mth power.

For nearly two hundred years no one could find anything wrong with this proposition. Nobody could actually prove it, either, but it had been around for a very long time, and it had been proposed, after all, by a very respected authority...

And then, in 1966, L. J. Lander and T. R Parkin found a counter-example, four fifth powers that add up to a fifth power:

275+845+1105+1335=1445.

And 20 years after that, the m=4 case of the proposition fell too, when another mathematician "noticed" that

2,682,4404+15,365,6394+18,796,7604=20,615,6734.

Attempting to generalise in mathematics on the basis of one or two special cases is always a risky business, of course, and one of the most telling examples I know involves an apparently innocent little problem in geometry.

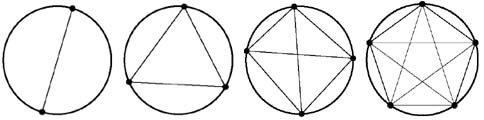

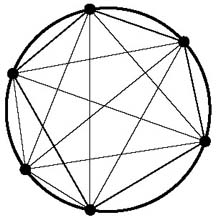

Take a circle, mark n points on the circumference, and join each point to all the others by straight lines. This divides the circle into a number of different regions, and the question is: how many? (It is assumed that no more than two lines intersect at any point inside the circle).

Now, for the first few values of n, namely 2, 3, 4 and 5, the number of regions follows a very simple pattern: 2, 4, 8 and 16.

And, in my experience, it is possible at this point to lure virtually anybody into "deducing" that when n=6 the number of regions will be 32.

But it isn't. It's 31!

And the general formula for the number of regions isn't the simple one we had in mind at all.

It's

(n4-6n3+23n2-18n+24)/24.

Surprising connections

In higher mathematics, some of the deepest surprises come about from unexpected connections between apparently quite different parts of the subject.

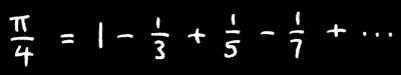

When we first meet the number $\pi=3.14159...$ , for instance, it is all about circles. In particular, if we take any circle, then $\pi$ is the ratio of circumference to diameter. \par Imagine the surprise, then, in the mid-17th century, when Leibniz discovered the following extraordinary connection between $\pi$ and the {\em odd numbers}:

While it is possible to prove this result, beyond all doubt, using the methods of calculus, I have yet to meet anyone who can explain this connection between circles and the odd numbers in truly simple terms.

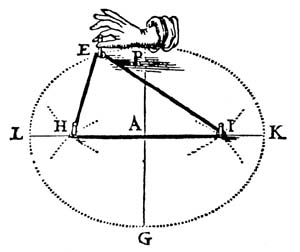

The ellipse, for instance, is a curve that was well known to Greek mathematicians, and it can be constructed by pulling a loop of string round two fixed points. These points, H and I, are called focal points.

At first sight, perhaps, this is "just" geometry. Yet, some 1,500 years after the ellipse's first appearance in this way, the German astronomer Kepler discovered that the planets move around the Sun in elliptical orbits, and - as if that were not coincidence enough - the Sun is always at one of the focal points! And explaining this elliptical planetary motion in terms of a gravitational force on each planet towards the Sun was eventually to be the cornerstone of Newton's most famous work, the Principia.

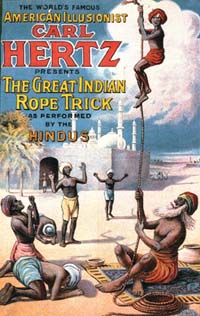

Not Quite the Indian Rope Trick

Yet I suppose the greatest mathematical surprise I've ever had came one rainy November afternoon in 1992, when I found myself proving a strange new theorem.

I was trying to give a new twist to an old problem in dynamics, first studied by Daniel Bernoulli in 1738. He had considered a hanging chain of several linked pendulums, all suspended from one another, and discovered various different modes of oscillation.

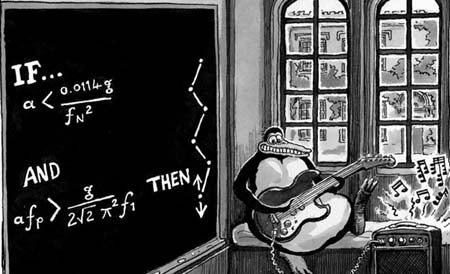

My theorem showed how it is possible to take all these linked pendulums, turn them upside-down, so that they are all precariously balanced on top of one another, and then stabilise them in that position by vibrating the pivot up and down. The upshot of the theorem (which appears on the blackboard in the Steve Bell cartoon at the beginning of this article) is that the "trick" can always be done if the pivot is vibrated up and down by a small enough amount and at a high enough frequency.

Computer simulations suggested that the upside-down state could in fact be very stable indeed, and this was borne out when a colleague of mine, Tom Mullin, confirmed the theorem experimentally. The photograph below shows an upside-down 50 cm triple pendulum, with the pivot vibrating through 2cm or so at about 40 cycles per second, and the chain of pendulums is seen wobbling back towards the upward vertical after a fairly severe initial disturbance.

not quite the Indian rope trick

As soon as we started calling this gravity-defying experiment "Not Quite the Indian Rope Trick" we found that newspapers, radio and TV all began getting interested, and Tom and I have had a great deal of fun with this topic over the years. My scientific papers on the subject have even been acquired by the archives of the Magic Circle in London, which would surely have astonished a certain 10-year old boy in 1956. (The papers are kept, I understand, in a box file called Sundry Ephemera).

In the end, though, it is not all that important whether mathematics might or might not explain a particular magic trick.

What matters, surely, is the extent to which surprising results like this may help persuade the wider public that mathematics, at its best, has a certain magic of its own.

About this article

This is a shortened version of an article that appeared in the European Mathematical Society Newsletter, Issue 49, 2003.

David Acheson's latest book "1089 and All That" (Oxford University Press 2002) is an original attempt at bringing some of the ideas and pleasures of mathematics to a wide public, and is a Plus favourite. Your can read our review in issue 23 of Plus, and further details may be found at David Acheson's homepage.

Recently, David Acheson gave a lecture in Cambridge on the topics covered in this article, and more. The lecture was filmed by Science Media Network, and is available to watch online.