With France's referendum on the European constitution just around the corner, the big question - "where does Britain stand in Europe?" - will no doubt fill the airwaves and column inches once more. And, once more, opinions will differ drastically and tempers will flare. So is there an objective, mathematical way to analyse complex relationships within a group of countries? Should such an analysis be based on economic or political considerations, popular opinion or people's preferred holiday destinations?

Why not base it on musical taste, thought a team of Oxford scientists, and set to work on the Eurovision Song Contest, the second hugely important European event to take place this month.

The European Song Contest is a perfect example of what mathematicians call a complex system. This consists of a group of objects (countries) which interact with each other (by giving each other points for their songs), and this interaction can be tracked over time. A statistical analysis of the system can then give some insight in the nature of the interaction. For example, it can show whether certain countries form cliques that always vote similarly, or whether a country's voting is largely "in tune" with that of the whole group.

The need to analyse complex systems arises nearly everywhere: a psychologist might be interested in the way a group of individuals bond, a neurologist in the way neurons in the brain interact, and an economist in the way big trade networks function.

Tools for analysing such systems are always in demand and the aim of the four scientists, Daniel Fenn, Omer Suleman, Janet Efstathiou and Neil F. Johnson, was to illustrate their methods, rather than draw cultural or political conclusions from Europe's musical taste (or lack of it).

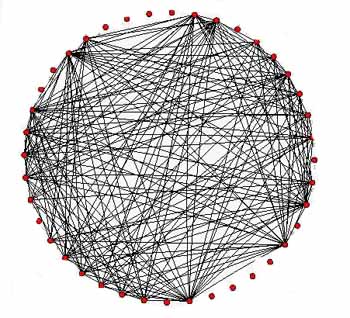

This network represents a song contest: each red dot stands for a country. There is a line between two countries if one has given points to or received points from the other.

In their paper, published on the physics arXiv last week, the scientists considered data from all the contests between 1992 and 2003, a period in which the number of participating counties stayed roughly the same and the rules did not change. According to these rules, each country chooses its 10 favourite songs and then ranks them by awarding each song 12 points, 10 points or between one and eight points. Each song must get a different number of points, and countries are not allowed to vote for themselves.

The team then performed six statistical tests to see whether the voting behaviours of different countries are in some way related. In every statistical test you need a "control experiment" to compare your results to. Suppose, for example, that two countries always seem to vote the same way. Then, before you can deduce that their musical tastes are indeed related, you need to show that the two countries vote the same way significantly more often than would happen in a song contest in which the countries' voting is truly independent. To create such a control experiment, the team simulated a "random song contest", in which each country assigns its points randomly to 10 other countries. They then compared the results of all their tests to the random contest.

One such test, which the scientists say is new, involves seeing whether voting relationships between countries persists over time. If, for example, country A gives and/or receives points from another country B over a long period of time, then we can deduce that in some way the musical tastes of the two countries are related. Carrying out the same analysis between country A and all other countries in turn will show whether or not country A is "in tune" with the rest of Europe.

Another test observes the number of countries to which a given country A has awarded points and from which it has also received points. If a country has many such "reciprocal links", then one might deduce that its musical taste harmonises well with that of Europe in general.

The remaining tests were devised to identify cliques of countries whose voting behaviour is correlated. For example, the team checked to see whether two countries that have both received and/or awarded points to a third country are likely to give or receive points from each other.

And the results of the study? Ladies and gentlemen, mesdames et messieurs, we have a surprise: it is the UK that seems largely in tune with the rest of Europe, while France stands slightly askew. France's isolation is expressed further by the fact that it does not belong to any of the cliques identified by the study. These include the usual suspects, such as Greece and Cyprus, the UK and Ireland, and the Nordic countries, but also more surprising pairings such as Croatia and Malta, which are not geographically close.

So is Europe not what we thought it was?

We leave the interpretation of these results to other experts and look forward to an evening of quality music, broadcast by the BBC on the 21st of May.

Further reading

- Browse through Plus articles on statistics and its many applications in our archive.