If you want fewer traffic jams, it might be worth considering to remove a few roads. Don't believe it? Here are a few examples.

The Cheonggyencheon stream after the restauration. Image: stari4ek.

The closing of 42nd street, a very busy crosstown road in New York City, during Earth Day in April 1990, was expected to cause a traffic nightmare. Instead, as reported in The New York Times on December 25, 1990, the flow of traffic actually improved.

In 2003, the Cheonggyencheon stream restoration project began in Seoul, removing a six-lane highway. The project opened in 2005, and besides substantial environmental benefits, a speeding up of traffic was observed around the city.

Likewise, planners have called for the closing of parts of Main street in Boston and parts of the road connecting the Borough and the Farringdon underground stations, in London.

If closing roads might help traffic flow, the negative effects of expanding a road network can be observed as well. For instance, in the late 1960s the city of Stuttgart decided to open a new street to alleviate the downtown traffic. Instead, the traffic congestion worsened and the authorities ended up closing the street, which improved the traffic.

Remaining pillars of the Cheonggyencheon highway, which was removed.

Stories like these abound and as you might suspect, some mathematics is lurking behind them all. Indeed, in 1968, the mathematician Dietrich Braess, working at the Institute for Numerical and Applied Mathematics in Münster, Germany, proved that "an extension of a road network by an additional road can cause a redistribution of the flow in such a way that the travel time increases." In his work Braess assumed that the drivers will act selfishly, each of them choosing a route based on their own perceived benefit, with no regard for the benefit of other drivers. It's an assumption that reflects the harsh conditions of rush hour traffic rather well!

The phenomenon Braess observed, now called the Braess paradox, is not really a paradox, but just unexpected behaviour showing that we are not very well equipped to predict the outcomes of collective interactions.

The closing of 42nd street and the Cheonggyencheon stream restoration project are just reverse examples of the Braess paradox, where the removal of one or more roads improves the travel time along a road network.

Still a little skeptical about this Braess paradox? In the next section we will analyse the mathematics of a very simple example.

The case of the superfast road

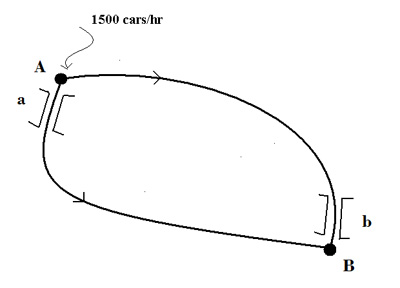

The road network shown below connects locations \textbf{A} and \textbf{B}.

Road network

John Nash, March 2008.

Let us observe that a Nash equilibrium is very different from, say, the equilibrium of the coffee cup sitting on my desk. A Nash equilibrium is dynamic, that is to say, to be maintained it needs to be fed, in our case, by the cars that enter the network at A every hour. That everybody achieves the same travel time means that at equilibrium no one is better off, although we have assumed that each driver acts selfishly, trying to minimise their own travel time with no regard for other drivers' interests. In other words, whether they want it or not, each driver is influenced by the collection of all the drivers' decisions.

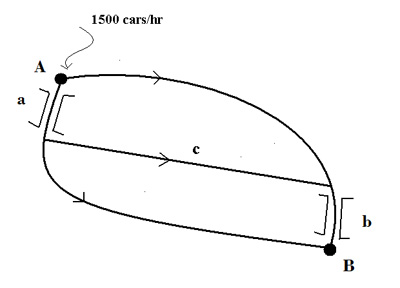

Now, the travel time, in minutes, for each of the two routes is \begin{center} \begin{tabular}{|c|c|} \hline Route 1: & $\frac{L}{100}+20$ \\ \hline\hline Route 2: & $\frac{R}{100}+20$ \\ \hline \end{tabular} \end{center} At equilibrium we can write $$ \frac{L}{100}+20=\frac{R}{100}+20\text{.} $$ Furthermore, the number of cars $L$, and $R$ must add up to the incoming flow. So, $$ L+R=1500\text{.} $$ Solving these two simultaneous equations, we find that% $$ L=R=750\text{.} $$ So, the traffic distributes evenly between the two routes, with a travel time of 27.5 minutes. We now assume that our road network is expanded with the addition of a super fast crossroad $c$, for which the travel time is 7 minutes.

Expanded road network

What happened? The superfast new road has proven to be too tempting for too many drivers, causing bad congestion and affecting the performance of the whole network. The drivers do not have any incentive to switch to the other routes, because they all have the same travel time. So, everybody gets stuck. In other words, selfish behavior has eroded the efficiency of the network, increasing travel time by 20%. Economists refer to this phenomenon as "the price to pay for anarchy". However, if the drivers agree to avoid route c completely, the travel time will decrease. This option is the same as adopting a cooperative strategy in which drivers split between the two preexisting routes. Actually, some road networks do have controller systems directing the traffic. In such networks the Braess paradox will not occur. It is only observed when drivers choose their own best routes.

Braess is a tricky paradox

It is easy to accept that when the incoming flow is sufficiently small, the Braess paradox will not occur. Actually, it has been observed that drivers, acting selfishly, change from their original routes to the superfast road with no increase in travel time.

On the other hand, one would think that a significant increase in the incoming flow of cars will make things worse. However, this is not always the case. In our example, scientists have conjectured that at a very high demand, there will be a "wisdom of the crowds" effect under which the new road would not be used. It appears, indeed, that the individual decisions within a large enough group of drivers may optimise the travel time for all. This conjecture was proved in 2009 by the mathematician Anna Nagurney, a professor in the Isenberg School of Management at the University of Massachusetts.

A way of experimenting with these ideas in our small example would be to use some algebra: replace the numbers with variables and see what relations between the variables imply that the paradox will or will not occur. That is to say, whether the travel time in the expanded network is larger than the travel time in the original network, or not.

Before we exit ...

... a few more comments are in order.

The Braess paradox appears in many contexts. For instance, the article If we all go for the blonde, uses a blonde of allegedly great alluring power to take the place of our superfast road, producing the same effect, a congested field. But if we keep to networks, the paradox has been observed with data traveling in a network of computers and with power being delivered on the grid. Moreover, in 2012 an international team of researchers proved, theoretically as well as experimentally, that the Braess paradox may occur in systems of electrons.

Getting somewhere?

Our example of the expanded road system shows that at equilibrium, the distribution of cars in the network does not need to be optimal. This brings us to another interesting concept, formulated by the economist Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923). Pareto declared a distribution of resources to be optimal if no individual can be made better off without making at least one other individual worse off. Such a distribution is called Pareto optimal.

In our example, the roads in the network are the resources. Ignoring the new road makes everybody better off, from the stand point of decreasing travel time. Thus, the equilibrium in the expanded network is an example of a Nash equilibrium which is not Pareto optimal.

Finally, let us observe that a distribution of resources described as Pareto optimal does not need to be fair in the social sense of the word. For instance, an allocation of resources in which I hog everything and you have nothing is Pareto optimal because the only way to improve your lot is for me to lose something. Efforts have been made by some economists, among them Ravi Kanbur of Cornell University, to reformulate the notion of Pareto optimality, adding a quantitative way of measuring fairness.

About the author

Josefina (Lolina) Alvarez was born in Spain. She earned a doctorate in mathematics from the University of Buenos Aires in Argentina, and is currently professor emeritus of mathematics at New Mexico State University, in the United States. Her long time interest is to communicate mathematics to general audiences. Lolina lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico with husband Larry and dog Lily. She walks every week many kilometres along the beautiful trails of Northern New Mexico. For more on her work, visit this website.