This article about complex numbers is a little advanced. See here for a basic introduction to complex numbers.

Many things in mathematics are named after Leonhard Euler, who probably was the most prolific mathematician of all time. In this article we explore a formula carrying his name which reveals a beautiful relationship between the exponential function and trigonometric functions. It also allows us to write complex numbers in an exponential way.

First of all, remember that a complex number has the form $x+iy$ where $x$ and $y$ are real numbers and $i$ is the square root of $-1$.

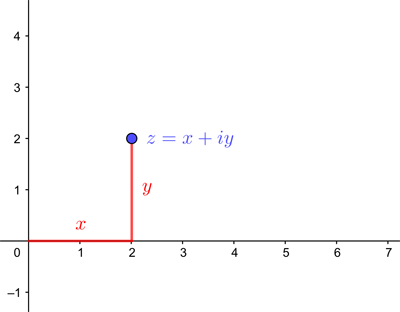

You can associate a complex number $z=x+iy$ with the point in the plane that has Cartesian coordinates $(x,y)$.

A complex number represented as a point on the plane in Cartesian coordinates.

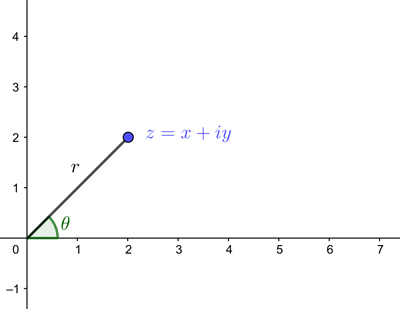

Now a point $(x,y)$ in the plane can also be described by its polar coordinates $(r,\theta)$. Here $r$ is the distance from $(x,y)$ to $(0,0),$ and $\theta$ is the angle formed by the line connecting $(x,y)$ to $(0,0)$ and the positive $x$-axis (measured anti-clockwise).

A complex number represented as a point on the plane in polar coordinates.

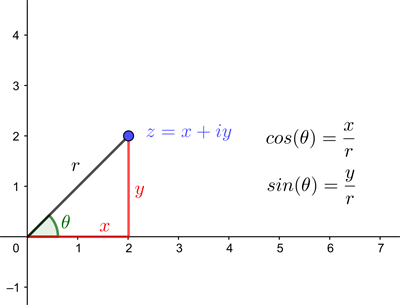

The relationship between the Cartesian coordinates $(x,y)$ and the polar coordinates $(r,\theta)$ can be worked out using a little trigonometry. It is $$x=r\cos{(\theta)}.$$ $$y=r\sin{(\theta)}$$

Trigonometry tells us the relationship between polar and Cartesian coordinates.

Going back to our complex number $z=x+iy$, we now see that it can also be written as $$z=x+iy=r\cos{(\theta)}+ir\sin{(\theta)}=r\left(\cos{(\theta)}+i\sin{(\theta)}\right).$$

The power of powers

Here comes the really interesting bit. As we explained in a piece from our Maths in a minute library, the cosine, the sine, and the exponential of a real number $\theta$ can be written as infinite sums of powers of $\theta$.

$$\cos{(\theta)} = 1 - \frac{\theta^2}{2!} + \frac{\theta^4}{4 !} - \frac{\theta^6}{6!} + ... ,$$ $$\sin{(\theta)} = \theta - \frac{\theta^3}{3!} + \frac{\theta^5}{5!} - \frac{\theta^7}{7!} + ... ,$$ and $$e^\theta = 1 + \theta + \frac{\theta^2}{2!} + \frac{\theta^3}{3! } + \frac{\theta^4}{4!} + \frac{\theta^5}{5! } + ....$$ Here $n! = n \times (n-1) \times (n-2) \times ... \times 2 \times 1.$ For all three of these series the beautiful pattern continues indefinitely. Choosing a particular value for $\theta,$ you will find that the infinite series \emph{converges} to $\cos{(\theta)},$ $\sin{(\theta)},$ or $e^\theta$ respectively.

Re-writing z

Now let's see what happens when we work out $$e^{i\theta}$$ using the infinite series representation. We get $$e^{i\theta}=1 + i\theta + \frac{(i\theta)^2}{2!} + \frac{(i\theta)^3}{3! } + \frac{(i\theta)^4}{4!} + \frac{(i\theta)^5}{5! } + ....$$ Now notice that the number $i$ raised to the powers $2$, $6$, $10$, etc, gives us $-1$. For example, $$i^6=i^2\times i^2\times i^2 = -1 \times -1 \times -1 =-1.$$ By contrast, $i$ raised to the powers $4$, $8$, $12$, etc, gives $1$. For example, $$i^4 = i^2 \times i^2 = (-1)^2 = 1.$$ Something similar happens for odd powers. The number $i$ raised to the powers $1$, $5$, $9$, etc, gives $i$. For example $$i^5 = i^4\times i = 1\times i = i.$$ By contrast, $i$ raised to the powers $3$, $7$, $11$, etc, gives us $-i$. For example, $$i^3=i^2\times i = -1 \times i = -i.$$ This means that our expression for $e^{i\theta}$ above becomes $$e^{i\theta}=1 + i\theta - \frac{\theta^2}{2!} -i \frac{\theta^3}{3! } + \frac{\theta^4}{4!} + i\frac{\theta^5}{5! } - \frac{\theta^6}{6!} - i\frac{\theta^7}{7!} ....$$ We can rearrange this series to gather together all terms involving $i$: $$\begin{array} {ccc} e^{i \theta} & = & 1 - \frac{\theta^2}{2!} + \frac{\theta^4}{4!} - \frac{\theta^6}{6!} ... \\ & +& i\left(\theta - \frac{\theta^3}{3! } + \frac{\theta^5}{5! } - \frac{\theta^7}{7!} ... \right)\end{array}$$

(Note that we are allowed to rearrange the terms of the series because it is absolutely convergent, though we won't prove this here.)

From our representations of $\cos{(\theta)}$ and $\sin{(\theta)}$ above, this means that $$re^{i\theta} =r\left(\cos{(\theta)}+i\sin{(\theta)}\right).$$ So, in summary, a complex number $z=x+iy$ can also be written as $$z=re^{i\theta},$$ where $$x=r\cos{(\theta)}$$ and $$y=r\sin{(\theta)}.$$ It is associated to the point in the plane that has Cartesian coordinates $(x,y)$ and polar coordinates $(r,\theta)$.Why do we care?

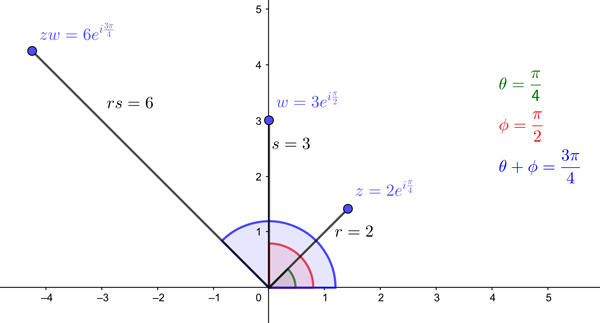

Euler's formula is beautiful in its own right, but it's also useful. Imagine you want to multiply two complex numbers $z$ and $w$. If you write them as $z=x+iy$ and $w=u+iv$ then this is tedious. You have to work out $$(x+iy)(u+iv)$$ which involves multiplying out brackets. It's even more tedious if you're multiplying more than two complex numbers. And it doesn't give you a sense of where on the plane the point corresponding to $zw$ might lie. However, writing $z$ as $re^{i\theta}$ and $w$ as $se^{i\phi}$ makes the multiplication easy: $$zw = \left(re^{i\theta}\right)\left(se^{i\phi}\right) = rse^{i\left(\theta+\phi\right)}.$$ All you have to do is multiply the two \emph{radii} $r$ and $s$ and add the two polar angles. From this you can also immediately tell where on the plane the point corresponding to $zw$ lies. We have illustrated this below for $z=2e^{i\frac{\pi}{4}}$ amnd $w=3e^{i\frac{\pi}{2}}$ so $zw=6e^{i\frac{3\pi}{4}}$.

Euler's identity

Finally, we have a quick look look at what's often described as the most beautiful equation in mathematics: Euler's identity:

$$e^{i\pi}+1=0.$$

We can see that the equation is true because $$e^{i\pi}+1=\cos{(\pi)}+i\sin{(\pi)}+1=-1+0+1=0.$$

People love this equation because it combines three of the most important numbers in maths — $0$, $1$, $e$, $\pi$, and $i$ — with three of the most important mathematical operations— addition, multiplication, and exponentiation. It almost feels like a miracle that these numbers and operations combine in such a beautifully elegant way.

About this article

Marianne Freiberger is Editor of Plus.

This article is part of our collaboration with the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences (INI), an international research centre and our neighbour here on the University of Cambridge's maths campus. INI attracts leading mathematical scientists from all over the world, and is open to all. Visit www.newton.ac.uk to find out more.