Outer space: On a clear day

R is the radius of the Earth, H is your height and D is how far you can see.

...You can see forever, according to Alan Lerner's Broadway musical. But can you? How far can you see? Just how far away is the horizon?

Let's assume the Earth is smooth and spherical, so no intervening hills obscure your view, and ignore the effects of light refraction as it passes through the atmosphere, along with the effects of any rain or fog. If your eyes are a height $H$ above the ground and you look towards the horizon, then the distance to the horizon, $D$, is one side of a right-angled triangle whose other two sides are $H$ plus the radius $R$ of the Earth, and $R$. Using Pythagoras' theorem for this triangle we have

$(H+R)^2 = R^2 + D^2.$

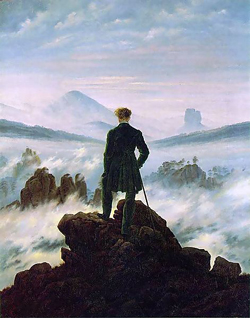

The wanderer above the sea of fog by Caspar David Friedrich.

Since the average radius of the Earth is about 6400 km and much greater than your height $H$, we can neglect $H^2$ compared to $R^2$ when multiplying out the square of $H+R$. This means that the straight-line distance to the horizon is just

$D = \sqrt{2HR}$$

to a very good approximation. If we put the radius of the Earth into the formula we get (measuring $H$ in metres)

$D = 1600 \; metres \times \sqrt{5H} \approx \sqrt{5H}\; miles.$

For someone of height 1.8m we have $\sqrt{5H} = 3$ and the distance to the horizon is $D = 4800$ metres, or 3 miles to very good accuracy. Notice that the distance that you can see increases like the square root of the height that you are viewing from, so if you go to the top of a hill that is 180 metres high you will be able to see about ten times further. From the top of the world's tallest building, the Burj Dubai in the Emirates you might see for 102 kilometres, or 64 miles. From the summit of Mount Everest you might see for 336 kilometres, or 210 miles - not quite forever, but far enough.

Problem 1: Above we have calculated the straight-line distance to the horizon point. Show that if we take the curvature of the Earth into account, then the "walking" distance over the Earth's surface to the horizon point is $$R\cos^{-1}(R/(R+H)),$$ but this becomes equal to $(2RH)^{1/2}$ when we use the approximation that $R>>H$.

Problem 2: You see something, like a cloud or a hot air balloon, high in the sky beyond the horizon and you know its maximum possible height above the ground. Can you work out how far away it could be?