Plus Advent Calendar Door #8: Asymptotic expansions

If you're familiar with some calculus, then you might know that certain types of functions can be approximated using convergent series. (If that's news to you, then you might first want to read this short article and familiarise yourself with the idea.)

It turns out that some functions can also be approximated using series that don't converge at all. This seems weird at first: a divergent series (one that doesn't converge) can't be considered to be "equal to" a single finite value (as a convergent series can be) so how can you possibly use it to approximate anything? Here's an answer to this question, which was first formalised by the French mathematician Henri Poincaré in 1886.

To illustrate the idea behind so-called asymptotic expansions, let's first imagine that we have some function $f(x)$. We would like to describe the behaviour of the function as $x$ goes to infinity — in other words, we would like to describe the asymptotic behaviour of the function.

Now imagine that you also have an infinite series (i.e. infinite sum) of the form $$S(x)=a_0+\frac{a_1}{x}+\frac{a_2}{x^2}+\frac{a_3}{x^3}+\frac{a_4}{x^4}+...$$ where $a_0$, $a_1$, $a_2$, etc are fixed coefficients. We are not making any assumptions on whether or not $S(x)$ converges for given values of $x$.

The reason we are considering a series of this form is to do with the way the functions $1/x^n$ (for $n$ a positive integer) behave as $x$ goes to infinity. For each $n$ the function $1/x^n$ goes to $0$ as $x$ goes to infinity — and it drops down to $0$ faster than the preceding function $1/x^{n-1}$.

Now given some positive integer $N$ we can chop the sum $S(x)$ off after the $Nth$ term and consider the partial sum $$S_N(x)=a_0+\frac{a_1}{x}+\frac{a_2}{x^2}+\frac{a_3}{x^3}+\frac{a_4}{x^4}+...+\frac{a_N}{x^N}.$$ Since we are interested in approximating the function $f(x)$, we can then look at the difference $R_N$ between the value of the function at $x$ and the partial sum evaluated at $x$: $$R_N=f(x)-S_N(x).$$ This difference is also called the remainder. Now if we were hoping that our series converges, we'd look at what happens to the remainder (for some fixed value of $x$) as $N$ tends to infinity, hoping that it tends to $0$. But since we're not banking on convergence we won't do that. Instead we will keep $N$ fixed and look at what happens as $x$ tends to infinity. Here comes the definition. We say that $S(x)$ is an asymptotic expansion of $f(x)$ if there exists a real number $K$ so that for all values of $x$ that are sufficiently large we have $$R_N(x)\leq \frac{K}{x^{N+1}}.$$ Since the right hand side of this inequality tends to $0$ as $x$ tends to infinity, the inequality tells us that the remainder $R_N(x)$ also tends to $0$ as $x$ tends to infinity. So even though our series may diverge, the partial sum $S_N(x)$ still gives you a good approximation of $f(x)$ as long as $x$ is sufficiently large. Note that the meaning of "sufficiently large" may depend on $N$. If you choose a different value for $N$ (for example by looking at a longer partial sum) then the threshold $x$ has to cross to count as "sufficiently large" may change too. Another thing our expression above tells us is that $R_N(x)$ drops to $0$ as $x$ goes to infinity no slower than $K/x^{N+1}$ drops to zero as $x$ goes to infinity. In other words, the first term that we neglected when we formed our partial sum $S_N$ (the term which involved $x^{N+1}$) tells us something about the behaviour of the remainder $R_N(x)$ as $x$ goes to infinity.

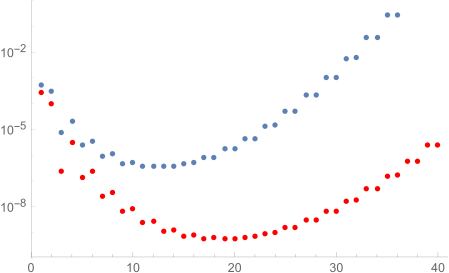

The remainder function RN corresponding to the asymptotic expansion of the gamma function, plotted against the number of terms N. Blue dots show the value of the remainder for x=2 and red dots for x=3. As you can see, in both cases the remainder decreases at first with the number of terms N, until it reaches a minimum value: truncating the expansion at this value of N gives you the best approximation to the function. The remainder then increases, so the approximation becomes less and less accurate.

Asymptotic expansions can be really useful when approximating functions. Even when your function can also be approximated by a convergent series (see here) it may be that the convergence is very slow, so you'd have to consider a very long partial sum to get a good approximation. When that is the case, an asymptotic expansion may do a better job, as it may deliver you a good approximation with fewer terms. See Stokes phenomenon: An asymptotic adventure for a problem where this is the case.

Even though asymptotic expansions involve divergent series (which are famous for being tricky) you can work with them quite nicely. For example, if you have two functions with two corresponding asymptotic expansions, then the asymptotic expansion of the sum (or difference, or product, or quotient) of the functions is the sum (or difference, or product, or quotient) of the asymptotic expansions of the original functions.

Also, if a function has an asymptotic expansion, then this expansion is unique — there's no ambiguity. This doesn't work the other way around though: two different functions can have the same asymptotic expansions. A poignant example comes from adding an exponentially small term to a function $f(x)$ to get an new function $$g(x)=f(x)+e^{-x},$$

two functions $f$ and $g$ have the same asymptotic expansion, so if the exponentially small terms is important to you for some reason, you need to be careful when using asymptotic expansions.

The definition we gave here is somewhat specific in that we were looking at the behaviour as $x$ tends to infinity. There's a more general definition of an asymptotic series, which works when you are trying to describe the behaviour of a function as $x$ tends to some finite number $L$. It even works when $x$ is a complex variable, rather than a real one. See Wikipedia to find out more.

This article relates to the Applicable resurgent asymptotics research programme hosted by the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences (INI). You can see more articles relating to the programme here.

Return to the Plus advent calendar 2021.

This article is part of our collaboration with the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences (INI), an international research centre and our neighbour here on the University of Cambridge's maths campus. INI attracts leading mathematical scientists from all over the world, and is open to all. Visit www.newton.ac.uk to find out more.