What Planck saw

Cosmologists gathered in the Netherlands last week to discuss a new view of the Universe. The Universe as seen by Planck was an international conference to discuss the recently released scientific results from the Planck satellite, including two particularly striking snapshots of the early Universe.

Planck has been casting its gaze back to the very beginning of the Universe, to around 380,000 years after the Big Bang, when the Universe had cooled enough to free photons from the grip of matter for the first time in a burst of radiation known as the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB). (You can read more in Bang, crunch, freeze and the multiverse.) These photons have been travelling ever since and now fill the sky with a fairly constant glow of electromagnetic radiation of around 1mm in wavelength. This radiation was first detected in the 1960s and provided evidence that our Universe did start with a Big Bang. The COBE and WMAP satellites provided a closer look, revealing tiny fluctuations in the CMB that are understood to be the very first seeds of stars, galaxies and other structures in the Universe.

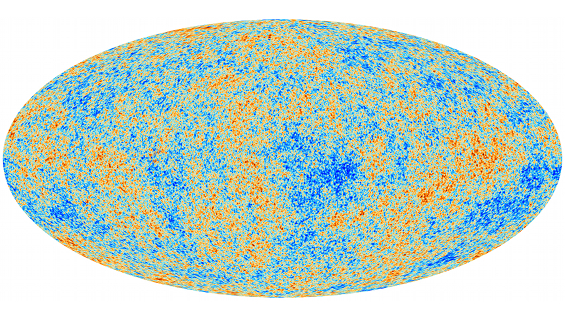

The all sky map of the temperature fluctuations in the CMB, as seen by Planck. (Image credit ESA and the Planck Collaboration)

Planck has provided a higher resolution version of the WMAP's iconic image showing these tiny temperature fluctuations in the CMB across the whole sky. It took energy for these ancient photons to pull away from matter: if they were in a more dense part of the Universe they lost more energy in extricating themselves and so appear today with a lower energy and hence temperature, indicated by the blue in this image.

One of the major assumptons of the standard model of cosmology is that the Universe started out essentially the same everywhere. Minute random fluctuations in the distribution of matter (both ordinary and dark matter) in this baby Universe were amplified by the period of rapid inflation in the first 10-32 seconds known as the Big Bang.

During the next 380,000 years the ordinary matter and photons had such high energies that their repeated collisions effectively tied them particles together. Usually the gravitational forces of any larger clumps of ordinary matter remaining at the end of the Big Bang would attract more matter leading to clumping. But the radiative forces of the photons this matter compensated for the gravitation; and so the fluctuations in the distribution of ordinary matter in the Universe remained essentially unchanged during this period. Dark matter, however, as the name suggests, does not interact with light and so the fluctuations in dark matter were still free to grow due to gravitational forces. (You can read more about dark matter in What is dark matter?.)

Around 380,000 years after the Big Bang the Universe cooled to a point such that stable atoms could form and photons could escape from the clutches of matter. Now this ordinary matter could also begin to accumulate under the forces of gravitation. Large scale structures of dark matter had already accumulated into a cosmic web which exerted a gravitational force on the ordinary matter. Thus the cosmic web became a hidden skeleton for the growth of structures of ordinary matter until eventually stars and galaxies were formed a few hundred million years later.

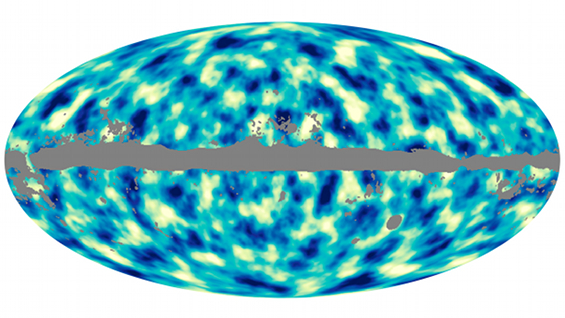

The all-sky map of the dark matter distribution in the Universe. Dark blue areas represent denser regions, lighter areas are less dense regions, and the grey portions are those parts of the sky obscured by the foreground, mainly from the Milky Way but also nearby galaxies. (Image credit ESA and the Planck Collaboration)

The Planck scientists have just released their first picture of this cosmic web of dark matter across the sky by analysing the way the CMB radiation has been bent by gravity as it has travelled through the Universe. Just as a glass lens can bend light, focusing or spreading the rays, large gravitational masses can similarly distort the path of the CMB photons. By analysing the difference in shapes in the CMB scientists have been able to reconstruct how the path of the radiaton has been bent, revealing the presence of large scale gravitational structures, believed to primarily consist of dark matter. (You can read more about gravitational lensing in Lensing helps see in the dark.)

Photons are deflected by all the structure along the line of sight back to when they decoupled from matter and these deflections leave subtle imprints in the temperature fluctuations in the CMB map, says Anthony Challinor, a cosmologist from the University of Cambridge's Institute of Astronomy who has been working on the Planck data. "For example, when we look through a big overdense clump of matter on the line of sight, angular structures in the CMB get magnified appearing bigger on the sky. Essentially, by looking how the typical size of 'blobs' in the CMB temperature map varies across the sky, we can reconstruct the lensing deflections and hence the [distibution of dark matter]."

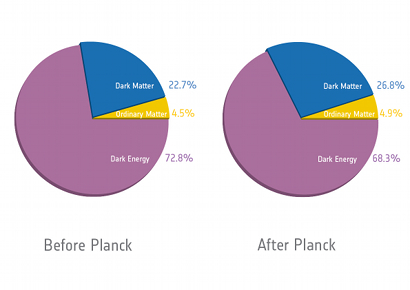

The new cosmic recipe. (Image credit ESA and the Planck Collaboration)

As well as revealing the spread of dark matter through the Universe, the new levels of precision in the CMB data have refined our recipe for the Universe: it contains slightly more ordinary and dark matter and less dark energy than previously thought. (You can read more about dark energy in What is dark energy?) Planck has also provided evidence that the Universe is flat, ruling out more complex curved shapes sharing the characteristics of a ball or a saddle.

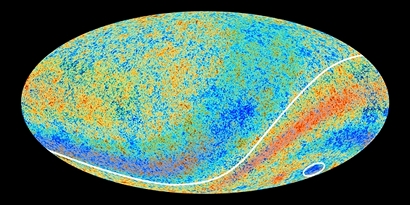

Planck’s anomalous sky: the hemispheric asymmetry and the cold spot. (Image credit: ESA and the Planck Collaboration)

In fact the Planck data closely agrees with predictions of the standard model of cosmology, meaning our understanding of the evolution of the Universe is fairly sound. "The theory of cosmic inflation in the early Universe stands up beautifully well to the exacting scrutiny of the Planck data," says Challinor. But in revealing the CMB at such high precision, Planck has confirmed some asymmetries in the data that were suggested from previous experiments. We might yet have to modify our standard model: perhaps not all parts of the Universe were created equal after all?