"It is only slightly overstating the case that physics is the study of symmetry", said Philip Warren Anderson, the 1977 Physics Nobel laureate. But, as in a beautiful picture or a striking face, an absence of symmetry can be just as important. François Englert and Peter Higgs have been awarded the 2013 Nobel prize in physics for explaining a broken symmetry at the heart of our understanding of particle physics.

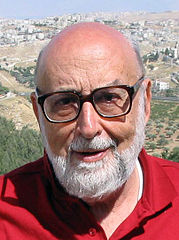

François Englert. Image: Pnicolet.

One of the most exciting recent events in physics — the discovery of tell tale signs of the Higgs boson in the Large Hadron Collider in 2012 — was the experimental confirmation of this explanation of symmetry breaking. In the 1960s theoretical physicists began to suspect that two of the fundamental forces — the electromagnetic force that governs the interactions of electrons and photons and the weak nuclear force that is responsible for radioactive decay — were in fact different aspects of a unified electroweak force. The electromagnetic force is mediated by force carrying particles called photons: when two particles interact it is by exchanging photons. The symmetry of the mathematical equations dictated that there had to be force carrying particles for the weak force that played the same role as the photon for the electromagnetic force. This symmetry predicted the existence of particles called W and Z bosons, which were experimentally observed in the 1980s when experimental physics finally caught up with the theory.

There was a problem, however: the symmetry decreed that these particles should have no mass, just like their electromagnetic equivalent, the photon. But in order to explain the relative weakness of the weak force these bosons had to have a mass. The answer to this puzzle was independently discovered by six physicists. Robert Brout (now deceased) and François Englert published their mathematical model of how these aspects of symmetry could be broken in the summer of 1964. Just one month later Peter Higgs published his papers that not only explained the same mechanism but also predicted the existence of new particle, now known as the Higgs boson. The model was also independently discovered by the US physicists Gerry Guralnik, Carl Richard Hagen and Tom Kibble, who published their work later that same year. (You can find out more about the Higgs boson and mechanism in Secret symmetry and the Higgs boson and Particle hunting at the LHC.)

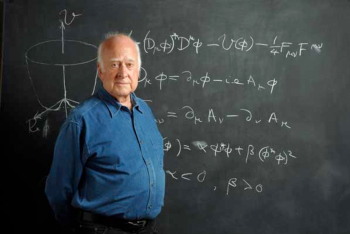

Peter Higgs. (Copyright Peter Tuffy, The University of Edinburgh.)

On 4 July 2012, after huge anticipation, the world watched as physicists at CERN finally announced that they had observed a new particle which matched the properties of the elusive Higgs boson. Their hesitation at making this claim earlier was because they could never hope to see the Higgs boson directly, as it immediately decays into other particles. It is the properties and behaviour of the particles it decays into that could be detected by the ATLAS and CMS experiments at CERN's Large Hadron Collider. Using existing theory without including the Higgs boson, it is possible to predict what the data collected by the LHC should look like as a result of the behaviour of all the other particles, known as the background. If the actual data looks different from the predicted background data in the right way (if it agrees with the predictions made by including the Higgs) then that counts as evidence that the Higgs does exist. (See the Plus article Countdown to the Higgs for more detail.) This discovery was the final confirmation that the theory first developed by Brout, Englert and Higgs was correct.

"This year's prize is about something very small that makes all the difference." said Staffan Normark, Permanent Secretary of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, referring to the tiny sizes of the particles, such as the Higgs boson, that are described by these theories. But the impact of the work of the 2013 Nobel laureates has been enormous.

"I cannot over stress the importance of the discovery," says Ben Allanach, a theoretical particle physicist from the University of Cambridge and one of the many people who was part of the search for the Higgs boson. "The mass mechanism that the Higgs boson is a signal for has had a huge impact on particle physics over the last fifty years. I think many of us felt that it had to be correct, although we were willing to let data dissuade us. This is the recognition of a triumph for fundamental physics that will stay in the history books for millenia to come. I am thrilled about the prize, and Englert and Higgs both deserve it well. Congratulations to François and to Peter!"

And as well as congratulating Englert and Higgs, we'd also like to congratulate Guralnik, Hagen and Kibble on their important contributions, and the hundreds of people working at CERN and the LHC for their role in one of the most exciting moments in Physics.