One thing that makes TV game shows fun to watch is that there's usually an element of luck involved. Even the brainiest of contestants needs to hedge their bets sometimes, and sometimes the result hinges on things that are totally out of their control. But how (un)lucky is (un)lucky? John Haigh looks at the probabilities of two popular examples.

Pointless

How lucky is lucky?

This show seeks to reward obscure knowledge: we can all name some football club that has won the FA Cup, but what answer might we give if the aim is to name such a club that other people won't think of?

The test used for obscurity of a (correct) answer is to count how many of 100 randomly selected people give that answer. So although teams like Manchester United or Arsenal will be very popular, I would be confident that Old Carthusians, Clapham Rovers or Blackburn Olympic would get very few mentions – probably zero, that much-desired "pointless" answer.

Four couples begin the game, three of them are eliminated over a series of rounds based on a wide variety of subjects. In the final round, the remaining pair select a topic from a list presented to them, and are allowed to offer three possible answers: they will win money if any of their answers are "pointless". Frequently, they will fail to do so, but do give correct answers chosen only by a small number – two or three – of the 100-strong pool. The presenters commiserate with the contestants on their bad luck in giving such good, but not winning, answers. But how unlucky have they really been, in the sense that, had a different set of 100 people been asked that question, an answer they gave would have been "pointless"?

Let $x>0$ be the number among the 100-strong pool that gave a particular answer. Then we will take $x/100$ as our estimate of the probability that a randomly selected person will give that answer, so that the probability a person does not give that answer is taken as $1-x/100.$ It follows that, with a different set of 100 randomly chosen people, the chance that none of them gave that answer is taken as $$ \left(1 - \frac{x}{100}\right)^{100}. $$ But a well-known approximation is that, when $x$ is small compared to $N$, then $$ \left(1 -\frac{x}{N}\right)^N \approx e^{-x}, $$ where $e \approx 2.1718$ is the basis if the natural logarithm. (You can read more in The making of the logarithm.) Now $$e^{-1} \approx 0.37, \;\; e^{-2} \approx 0.135 \mbox{\;\;and\;\;} e^{-3}\approx 0.05;$$ so even if just two people in the pool gave that answer, the chance it would have been pointless with another pool is quite small, about 0.135 or 13.5\%. For a single attempt, only if just one person had given their answer might the epithet "unlucky" be appropriate. But contestants do offer three answers, so the most frustrating outcome would be if all of them had attracted just one vote from the pool. With a different pool of 100 people, each answer has a 37\% chance of being pointless, so the chance of none of the three answers being pointless is $$(1 - 0.37)^3.$$ This puts the chance that at least one of them is pointless at $$ 1 - (1 - 0.37)^3, $$ about 75\%. And that is as unlucky as you can get in this game.The Million Pound Drop

In this game contestants face a series of questions, each of which has up to four possible answers displayed, but only one is correct. They begin with one million pounds and, with each question, must decide how to split their money among the possible answers. They may select one answer only, or spread it among two or more: any money placed on incorrect answers is lost, and they take away however much they have left after the eighth and final question. Two rules: first, all the money must be placed somewhere; second, at least one answer must attract no money. If they are sure of the answer, they do best to place all their funds on it, but what should they do when they are uncertain between two (or more) answers?

The concept of utility can help. Gambling scruples apart, having an extra £10 for certain is generally felt to be just as attractive as having a 50:50 chance of either £20, or zero, to be determined on the toss of a coin. But most people would rather have an extra £100,000 for certain than face a 50:50 chance of either £200,000 or zero. With these larger sums, twice as much money brings rather less than twice the benefits.

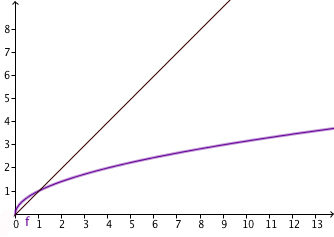

The black line is the graph of the function Y = X and the purple curve is the graph of the square root function.

About this article

John Haigh teaches the module Mathematics in Everyday Life at Sussex University. With Rob Eastaway, he wrote The hidden mathematics of sport, which has been reviewed on Plus.