Finding your place in the world

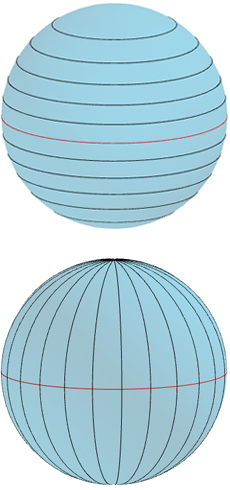

Lines of latitude (top) and longitude (bottom).

What do you do when you are lost? If you are lucky enough to have a smart phone, you'll probably use the GPS feature. This pin-points your global coordinates using information sent from satellites (see here). But what are those global coordinates?

Where are you?

Ordinary flat maps are often divided up into a grid formed by vertical and horizontal lines. The resulting grid boxes are usually labelled by letters (A, B, C, etc) in the horizontal direction and by numbers (1,2,3, etc) in the vertical direction. To find a location, say a particular street in your home town, you look up its coordinates, for example A4, in the index, and then find the grid box labelled by that letter and number. The street you are looking for will be within this box.

Navigation around the spherical Earth uses the same idea, only here the grid isn't formed by straight lines but by circles that lie on the surface of the Earth. One set of circles (which we can think of as horizontal) comes from planes that are perpendicular to the rotation axis of the Earth. These slice right through the Earth, meeting its surface in circles which are called lines of latitude. The radii of these circles vary: the largest one is the equator, which chops the Earth neatly into a Northern and Southern hemisphere. As you move North or South the circles become smaller, and at the poles they are just points.

The other set of circles (which we can think of as the vertical lines) come from planes that slice right through the Earth and contain the axis around which it rotates. Such planes meet the surface of the Earth in circles that contain both poles, are centred on the same point as the Earth itself and have the same radius as the Earth. One half of such a circle, running from the North to the South pole, is called a line of longitude or a meridian.

What's your latitude?

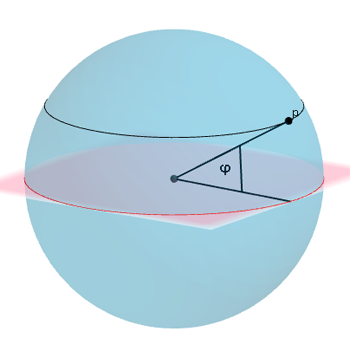

Lines of latitude and longitude are labelled by angles. Imagine a particular line of latitude, pick a point $p$ on it, and draw a line from $p$ to the centre of the Earth. Now measure the angle $\phi$ that this line makes with the plane containing the equator — it is the same no matter what point $p$ on the line of latitude you picked.

The latitude of the point p is given by the angle φ.

What's your longitude?

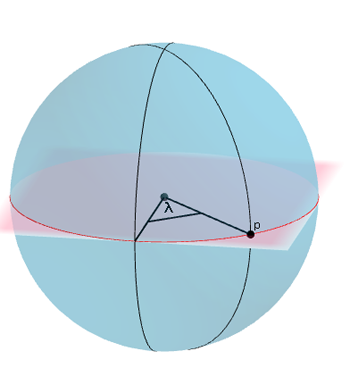

The angle of a line of longitude is measured with respect to a very special meridian: the one that runs from the North to the South pole and passes through Greenwich, South London. The angle defining another meridian, $\lambda$, is the angle through which you would have to rotate that meridian around the rotation axis of the Earth to make it coincide with the Greenwich meridian.

The longitude of the point p is given by the angle λ.

This gives you a way of finding a particular place on Earth. But how are you supposed to work out your coordinates in the first place, for example when you are lost at sea with your smart phone run out of battery? Find out here.