It's something that most of us dread: to find out one day that we aren't real, that we are living in a computer simulation. Yet some people who work at the forefront of science believe that the ultimate nature of reality might not be so far off this idea. They aren't suggesting that some intelligent being has programmed a simulation to create a world that dances to its tune, but that the Universe could be described, in the same way as a computer simulation, using only numbers and mathematics.

Max Tegmark, a physicist at MIT, is one of those people. In his new book Our mathematical Universe Tegmark suggests that the Universe itself is a mathematical structure. When we met him in London last week, he explained: "Suppose you are a character in Minecraft or some much more advanced computer game where the graphics are really good and you don't think you're in a game. You feel that you can bump into real objects and you can fall in love and get excited about stuff. And when you start studying the physical world in this video game, eventually you start discovering that, wow, everything is made out of pixels, and all these things that I used to think were 'stuff' are actually just described by a bunch of numbers. You'd undoubtedly be criticised by some friends saying, 'come on you're stupid, it's stuff after all.' But [someone] looking from outside of this video game would see that actually, all there was was numbers."

Max Tegmark

"And we're exactly in this situation in our world. We look around and it doesn't seem that mathematical at all, but everything we see is made out of elementary particles like quarks and electrons. And what properties does an electron have? Does it have a smell or a colour or a texture? No! As far as we can tell the only properties an electron has are -1, 1/2 and 1. We physicists have come up with geeky names for these properties, like electric charge, or spin, or lepton number, but the electron doesn't care what we call it, the properties are just numbers."

Even the space that those elementary particles live and move around in, so Tegmark suggests, is ultimately described by numbers and mathematical concepts. A number describes how many dimensions space has. As Einstein's theory of relativity tells us, space is curved and that curvature is described mathematically. We don't know whether the Universe is finite or infinite, and neither do we know its exact shape, but again it's mathematics that describes all possible shapes. Space, then, is just as mathematical as the particles that make up the "stuff" within it.

From this realisation Tegmark makes his daring leap: not only is the world described very accurately by mathematics, he suggests, it can be described only in terms of mathematics. It's a mathematical structure just like a cube, or a tetrahedron. Or, to go back to our example, it's entirely described by numbers and maths, just as a video game is encoded is a computer.

One obvious objection to raise against this idea is that there might be some sort of selection bias going on. Perhaps our minds just happen to be ideally suited to mathematical thought, so it's not surprising that we describe the world in terms of maths and that we can only really grasp those of its features that can be described mathematically. Perhaps there's lots more out there that is inherently unmathematical, but we just can't grasp it.

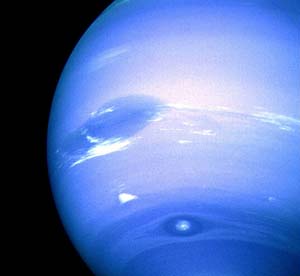

The planet Neptune was discovered after an unexpected wobble was observed in the orbit of Uranus. Calculations showed that this matched the wobble induced by the gravitational pull of an unseen planet. Image courtesy NASA.

But Tegmark points to the extraordinary success of mathematics. "We have again and again discovered that there was more stuff to learn than we knew of," he says. "So I think that's very likely to happen again. But again and again we have found that what we discovered could be described by mathematics and I think that is too profound a fact to just brush aside as meaningless. We discovered the planet Neptune with maths, we discovered the radio wave with maths, Peter Higgs predicted the Higgs boson with maths ... we can now calculate every single physical constant ever measured from just a list of 32 numbers. I think that is telling us something quite fundamental."

"If this idea that it's all maths is incorrect, then physics is ultimately doomed because we will hit this roadblock when there will be no more mathematical clues in nature for us to find. But if I'm correct in this guess then that's very good news for physics because there is no roadblock and our ultimate ability to figure things out is only going to be limited by our ability to do experiments and by our imagination and creativity."

And it's not just physics. Over the last few decades maths has made major inroads into all other sciences too, from biology and medicine to psychology and economics. Even one of the greatest remaining mysteries, the human mind and consciousness, is being attacked by neuroscientists using mathematical tools. If all of these areas can be understood mathematically, then we can be confident that we will eventually crack the riddles they pose.

Intrigued or still unconvinced? Then listen to our interview with Tegmark in our podcast, or read Our mathematical Universe (published by Allen Lane). We'll publish a review of the book on Plus soon.