In normal life higher dimensions smack of science fiction, but in mathematics they are nothing out of the ordinary. Intuitively we think of dimensions as ways in which we can move – up and down, left and right, forward and backwards – which leads us to believe we live in a three-dimensional world. Every point in this world is defined by three coordinates. We can't imagine living in a four-dimensional world because we simply can't conceive of another direction to move in.

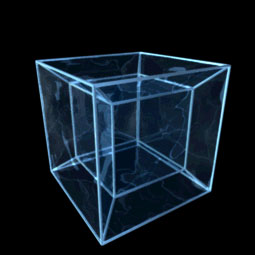

This is a projection of a four-dimensional cube, called a tesseract, into three dimensions. Image: Jason Hise.

But now imagine you are arranging to meet someone. Not only do you (theoretically) need to give them the three coordinates of the place you are meeting, you also need to tell them the time you are meeting. Thus, time and space together form a four-dimensional space: you need four numbers to specify a point.

There are also situations in which you need more than four numbers to specify what you are talking about. For example, if you're a sound engineer mixing music you might be working with 12, 24, or even 128 tracks. At each moment in time each of the, say, 24 tracks has a specific volume. This gives you 24 numbers defining a point in a 24-dimensional space of sound.

As you can see, the idea of higher dimensional spaces doesn't need to be as weird as it first sounds. Generally, a point in $n$-dimensional space is given by $n$ numbers, or coordinates. This is simple enough, but mathematicians go a step further and treat higher-dimensional spaces, and objects within them, as geometric objects, even though we can't visualise them. Algebra gives them the tools to do this. For example, the equation $$x^2+y^2+z^2=1$$ defines a ordinary sphere: a two-dimensional object which lives in three dimensions. By analogy, we say that the equation $$x^2+y^2+z^2+w^2=1 $$defines a hypersphere: a three-dimensional object which lives in four dimensions. You can define hyperspheres in higher dimensions in a similar way, and you can also define all sorts of other objects, such as hypercubes. Whenever mathematicians have proved a result in two and three dimensions, they always ask whether something similar holds in higher dimensions too. Sometimes this question is easy to answer and sometimes it isn't.

To find out more, read

- Kaluza, Klein and their story of a fifth dimension

- Exotic spheres, or why 4-dimensional space is a crazy place

- Packing spheres

About this article

This article now forms part of our collaboration with the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences (INI) – you can find all the content from the collaboration here.

The INI is an international research centre and our neighbour here on the University of Cambridge's maths campus. It attracts leading mathematical scientists from all over the world, and is open to all. Visit www.newton.ac.uk to find out more.