'Galileo and the Science Deniers'

Galileo and the Science Deniers

by Mario Livio

In these pandemic times, would you rather read a book that helps you escape, or one that gets you thinking deeper about what's going on? How about trying a book that can do both. Mario Livio's Galileo and the Science Deniers is a very entertaining read, featuring one of science's most colourful protagonists and his epic struggle with the Roman Inquisition. At the same time it carries a message that, 400 years later, is still acutely relevant: if you ignore science, history will prove you wrong. This applies whether you're a Pope or a President, and whatever the damage done by your denial, you can only hope it wasn't too serious.

"I have always been fascinated by Galileo. Not only because he can be regarded as the father of modern science, but also because of his fight for intellectual freedom, which is as important today as it was in his time," Livio said when we asked him for his motivation for writing the book. "Unfortunately, we are facing another phase of science denial and it happens on several fronts. There are climate change deniers, there are fundamentalists who deny Darwinian evolution and want to teach so-called 'intelligent design', and there are those who deny science by refusing to vaccinate their children. Even now with the coronavirus there are many people on the conservative right who say that it's all a hoax, or who ignore the advice of scientists.."

The father of modern science

Galileo is a great example in this context because the science he discovered is now so fundamental, it's hard to imagine where we'd be had it been suppressed. Galileo was the first to systematically use the (then newly invented) telescope to look into the night sky, observing, among other things, craters and mountains on the surface of the Moon, the phases of Venus, Sun spots, and the fact that the Milky Way is made out of an innumerable number of stars. Crucially, and perilously, Galileo promoted Copernicus's view that the Earth, rather than sitting at the centre of the Universe, is moving around the Sun.

Mario Livio.

In physics, too, Galileo made fundamental discoveries. He realised that a moving object, when left alone, will move along a straight line at constant speed. He also realised that an object that's thrown up into the air will describe the path of a parabola on its journey back down to Earth. And he saw that, in the absence of air resistance, objects thrown from a height will hit the ground at the same time, irrespective of their weight. Galileo's discoveries set the scene for Newton's laws of gravitation and motion, which form the basis of much of the physics we use today and have even put us on the Moon.

What entitles Galileo to be called the father of modern science are not just his discoveries, but also his methods. "Galileo started the methods we use today: experimentation, observation, and reasoning coupled together, and the use of mathematics to formulate theories," says Livio. "He started the idea that there are laws of nature which everything must obey, and that these laws can be formulated in the language of mathematics." Today these methods, as well as mathematics, are used across science — including the areas that help us fight viruses and epidemics, and produce the medical equipment and drugs needed to save lives.

The punishment

Galileo got into trouble mostly for the assertion that the Earth moves around the Sun. This not only contravened the general idea that god created the universe with us at the centre, but also directly contradicted a passage in Chapter 10 of the Book of Joshua, which has Joshua ordering the Sun to stop in its track around the Earth. Galileo's mightiest opponent was, unsurprisingly, the catholic church.

"The church also had scientists," says Livio. "The Collegio Romano in Rome had some of the most important scientists and mathematicians of the time. But they took very literal interpretations of the scripture. By contrast, Galileo understood that the bible was not written as a science book; it was written for our salvation. He said that, when there is a conflict between what we find out about nature from experiments and reasoning and the interpretation of biblical texts, it's the interpretation that needs to be changed."

This attitude is summed up beautifully in a famous quote from Galileo: "I do not feel obliged to believe that the same God who has endowed us with sense, reason, and intellect has intended us to forgo their use."

The trouble Galileo got into on account of these ideas was deep indeed. Heavily and unfairly slandered by a church report, he was eventually put on trial by the Roman Inquisition and found "vehemently suspected of heresy". After being forced to deny his life work with the words "I abjure, curse, and detest", Galileo was put on house arrest for the rest of his life. His famous book Dialogue on the two chief world systems was put on the index of forbidden books — where it remained until the middle of the 19th century. And this was getting off lightly. Had Galileo been convicted of outright heresy he would have burnt at the stake.

It took a long time, but today Galileo has been vindicated even in the eyes of the church. In 1992 Pope John Paul II officially declared that he was right.

From Galileo to today

In Galileo and the Science Deniers Livio beautifully describes both Galileo's work and his struggle for intellectual freedom. Livio is perfectly placed to do this. An astrophysicist himself, he has worked on a great-great-great-grandchild of the telescopes that Galileo employed, the Hubble space telescope. Seen through the eyes of an active researcher, Galileo's discoveries appear, not as historical facts, but as live components of a scientific effort that continues today.

Yet, this isn't a book written for scientists, or science historians. The drama of Galileo's life and his fascinating personality provide fertile ground for a skilled writer, and Livio has woven them into a gripping story anyone can enjoy. You won't need previous knowledge and, with Livio's light touch and careful effort to describe all the concepts, people, and historical issues he mentions, you won't have to reach for a search engine (and feel tempted to check the news and feel depressed).

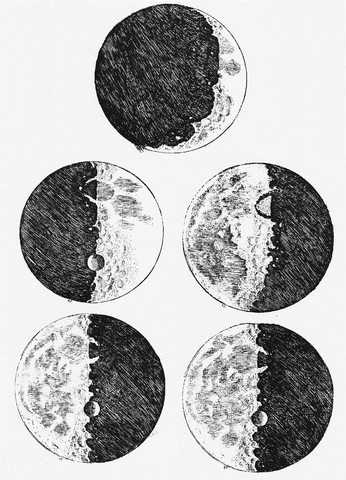

Galileo's sketches of the Moon from Sidereus Nuncius, published in March 1610.

If you do want to draw parallels to today, there is plenty to muse on. One of the reasons why Galileo's work prevailed, even during his lifetime and against the odds, is his passionate effort to disseminate his ideas. "All science at the time was written in Latin, but Galileo wrote most of his books in Italian because he wanted everybody to be able to read them," says Livio. "Galileo also embarked on an incredible outreach campaign by convincing the Tuscan court to fund the manufacturing of telescopes and to actually send them to influential people all across Europe, with instructions on how to use them." Those who didn't have telescopes could benefit from Galileo's impressive drawings, which beautifully depict the discoveries he had made in the sky.

There's an obvious lesson for scientists here: help the public know about your work and understand it. "Scientists owe it to the public [to communicate their work] because much of science is funded by the public," says Livio, "In addition, science is an integral part of human culture. In the same way we study Shakespeare, we should also know about science." Indeed, as Livio demonstrates in the last chapter of the book, the schisms we perceive today, between science and the humanities, or between science and religion, or science and spirituality, is something Galileo himself would have found abhorrent.

At the moment, of course, we are all getting a crash course in some science. We are learning about epidemiology and the role of maths in it, about the biology of viruses, and the scientific methods used to develop drugs and vaccines, which can't be cut short no matter how urgent the need. We are also learning that, in contrast to popular belief, science is as much about dealing with uncertainty as it is about producing certainty.

Yet even now, science denial is never far. In the US protesters are taking to the streets to oppose the lockdowns, encouraged by far-right groups, religious fundamentalists and anti-vaccination campaigners. "When you look at some of the daily briefings [in the US], we see how politicians try to paint a rosier picture than what it actually is," says Livio. "Often there is a gap between what the scientific advisers say and what President Trump says. So this business of denying science is around even now. "

"The main message I wanted to convey is that we need to listen to science. We have to find ways of stopping arguments from politics, or religion, from interfering with the interpretation and progress of science." Galileo's story, apart from providing welcome entertainment for boring lockdown evenings, serves as a potent reminder of the importance of freedom of thought, and of just how precious our gift for understanding the world through science really is.

- Book details:

- Galileo and the Science Deniers

- Mario Livio

- hardback — 304 pages

- Simon & Schuster (2020)

- ISBN 978-1982147167

About this article

Marianne Freiberger, Editor of Plus, interviewed Livio in April 2020.