Guessing is good for you

It's lunchtime, and I'm waiting in the cafe queue to buy a sandwich along with everyone else. What a lot of sandwiches... Imagine if everyone piled their sandwiches one on top of another... I wonder how high the mighty tower of sandwiches might be? Let's see... 60 million people in the UK, say 1 in 8 is having a sandwich right now, each sandwich might be about 3cm thick including filing, so that's... over 200km high!

You might say I'm thinking too much about sandwiches, but I'm actually exercising my number sense. Which, along with allowing me to make quick guesses about how big things are or how many there might be, also might be helping me get better at calculus and algebra. Researchers Michèle Mazzocco, Lisa Feigenson and Justin Halberda, from John Hopkins University, have shown that being good at formal mathematics is linked to having a good innate number sense. See, I'm not waiting in the sandwich queue, I'm studying!

Though people often think of mathematics as a pinnacle of intellectual achievement of humankind, research reveals that some intuition about numbers, counting and mathematical ability is basic to almost all animals. For example, creatures that gather or hunt for food keep track of the approximate number of food items they procure in order to return to the places where they get the most sustenance. Humans share this very basic "number sense," allowing them, at a glance, to estimate the number of people in a subway car or bus, Halberda says.

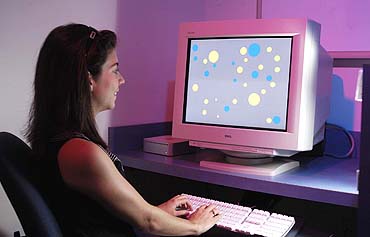

The students were flashed a group of yellow and blue dots,

and had to estimate which colour group was bigger.

The Johns Hopkins team wondered whether this basic, seemingly innate number sense had any bearing on the formal mathematics that people learn in school. So the researchers asked 64 14-year-olds to look at flashing groups of yellow and blue dots on a computer screen and estimate which dots were more numerous. Though most of the children easily arrived at the correct answer when there were (for example) only 10 blue dots and 25 yellow ones, some had difficulty when the number of dots in each set was closer together. Those results helped the researchers ascertain the accuracy of each child's individual number sense. (You can test your own number sense on the New York Times website.)

They then examined the teenagers' record of performance in school math all the way back through kindergarten, and found that students who exhibited more acute number sense had performed at a higher level in mathematics than those who showed weaker number sense, even controlling for general intelligence and other factors.

"What this seems to mean is that the very basic number sense that we humans share with animals is related to the formal mathematics that we learn in school," Halberda concludes. "The number sense we share with the animals and the formal math we learn in school may interact and inform each other throughout our lives."

Though the team found this strong correlation between number sense and scholastic math achievement, Halberda cautions against concluding that success or failure in mathematics is genetically determined and, therefore, immutable. "There are many factors that might affect a person's performance in school mathematics," Halberda says, "What is exciting in our result is that success in formal mathematics and simple math intuitions appear to be related."

What might be very exciting indeed is if our mathematical intuition can be trained. Mathematical guessing questions like the sandwich example above are called Fermi problems after the Italian physicist and mathematician Enrico Fermi. Fermi problems are already used in maths and science classrooms to practise problem solving skills, to gain an understanding of scale, and also to entertain. But perhaps these might be more than just fun, they might also train your brain to work better next time you have to do some serious maths.

Further reading

You can read the original paper in Nature, or read more in an article from the New York Times.

Plus has a number of articles on mathematical ability:

- Natural born mathematicians

- Speechless maths

- Evolutionary maths

- Aping around with numbers

- Counting canines

And you can try your hand at lots of Fermi problems from Hampton University and the University of Maryland.