Guilt counts

Guilt, so some people have suggested, is what makes us nice. When we do someone a favour or choose not to exploit someone vulnerable, we do it because we fear the guilt we'd feel otherwise. If this is the case, then guilt is what holds together human society, as society is to a surprising extent based on cooperation and trust. It would be interesting to know what neural processes generate guilt, not just to answer fundamental psychological questions, but also to understand disorders that are associated with an excess or lack of guilt, such as anxiety and psychopathy.

Why do you trust?

A team of neuroscientists, psychologists and economists have this month produced some new results in this area, using a model from psychological game theory. "One idea is that most people cooperate because it feels good to do it. And there is some brain imaging data that shows activity in reward-related regions of the brain when people are cooperating," says psychologist Luke Chang, one of the scientists behind the research. "But there is a whole other world of motivation to do good because you don't want to feel bad. That is the idea behind guilt aversion."

To test this idea the researchers used a commonly-studied mathematical game, called the trust game. It involves two people, an investor and a trustee. The investor gives a certain amount of money to the trustee. The amount is then multiplied by some factor, usually 3 or 4, and the trustee then has the chance to return some, all, or none of the money to the investor.

How can we predict how people will behave in this game? The traditional approach to game theory assumes that players are rational and completely selfish. Under this assumption trustees keep all the money, abusing the investors' trust. Realising this, investors don't hand over any cash in the first place, so no interaction takes place at all.

In this new study the researchers replaced the selfishness assumption with one of guilt aversion. They assume that the trustee simultaneously tries to maximise their financial pay-off and minimise the guilt they expect to feel if they let their partner down. Guilt is defined as the failure to meet the partner's expectations. So if the investor expects to get an amount $E_1$ back from the trustee and the trustee returns $S$, then guilt can be quantified as $E_1-S$ if $S

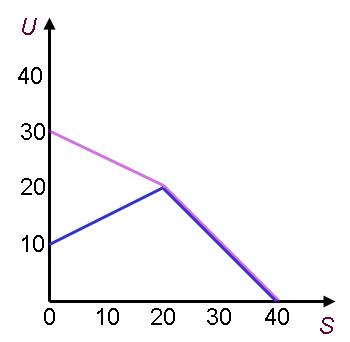

Suppose the total T=40 and the trustee believes that the investor expects to receive an amount E2=20. The plot shows U versus S for θ=1.5 (blue) and θ=0.5 (pink). For θ=1.5 there is a maximum at S=20 and for θ=0.5 there is a maximum at S=0.

The researchers tested their model on 30 volunteers who played repeated rounds of the trust game. On the whole, the volunteers behaved as the model predicts: they typically returned close to the amount they believed the investor expected back. After playing the games, they also reported that they would have felt more guilty had they returned less. This, so the researchers say, suggests that anticipated guilt really does play a role in decisions to cooperate.

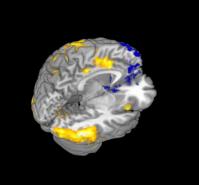

The researchers also used fMRI scans to monitor the brain activity of trustees during games. They found that participants who chose to honour trust by returning close to the amount that was expected of them showed increased activity in one network of brain components, while those that abused trust showed increased activity in another network. These two networks compete, but on the whole the network connected to honouring trust wins out.

An fMRI image showing areas of the brain associated with the competing motivations of minimising guilt (yellow) and maximising financial reward (blue) when participants decide whether or not they want to honor an investment partner's trust. (Image courtesy Luke Chang/UA psychology department.)

The results chime with existing evidence. Previous studies have linked the brain network associated to an abuse of trust to neural processes that compute value and reward. The network associated to honouring trust has been linked in previous studies to feelings of guilt, anger, social distress and empathy for others. "These studies support our conjecture that the prospect of not fulfilling the expectations of another can result in a negative affective state, which in turn ultimately motivates cooperative behaviour," say the researchers in their paper. "Perhaps the function of this frequently observed network is to track deviations from expectations and bias actions to maintain adherence to the expectation such as a moral rule or social norm."

So the study suggests that when you do someone a favour without expecting anything in return, it's because the relevant parts of your brain signal that falling short of the other person's expectations would lead strong feelings of guilt. There's a caveat though. Rather than guilt — feeling bad for not meeting expectations — the driving emotion may be empathy — the ability to "feel" the other person's disappointment when their expectations aren't met. It's a subtle difference and more work is needed to prise apart these two emotions.

The game theoretical model used in this study may seem surprisingly simple, but it's got an edge over traditional models used in economics, which have often been criticised for failing to take account of human nature. They usually assume that "players" are rational, self-interested and undeterred by complex social emotions such as guilt. This is where the inter-disciplinary approach involving both psychologists and economists can lead to useful results. "In the end, it's a two-way exchange," says economist Martin Dufwenberg, who co-authored the study. "Economists take inspiration from the richer concept of [humanity] usually considered in psychology, but at the same time they have something to offer psychologists through their analytical tools."

The study, Triangulating the neural, psychological, and economic bases of guilt aversion by Luke Chang, Alec Smith, Martin Dufwenberg and Alan G. Sanfey, has appeared in the journal Neuron.