Is it the theory?

If quantum mechanics predicts such strange things about the world (see this article) then why don't we simply discard it and look for a better theory? The quick answer is that it's been far too successful. We could write several articles about its many uses in real life, but let's just say that you wouldn't be reading this article without it — there'd be no internet.

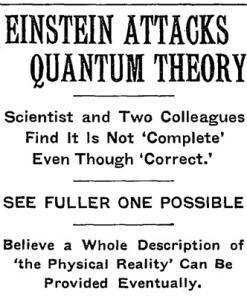

This is a headline from an article in the New York Times, published in 1935. Einstein was skeptical of the concept of entanglement and has misgivings about quantum mechanics as a theory.

What's perhaps even more compelling is that some of the weird quantum phenomena that were considered fictitious when the theory was first developed have now been proven to exist. An example is something called quantum entanglement. It predicts that two particles can become linked and remain so even when they are moved a large distance apart: when something happens to one of the particles, something corresponding happens to the other. Einstein called this "spooky action at a distance". "At the microscopic level we are probing the limits of quantum entanglement with technology in ways that are much more observable," says Sean Carroll, physicist and cosmologist at the California Institute of Technology. "The idea was invented by Einstein and [Erwin] Schrödinger back in the 1930s, but it was pretty hypothetical — we didn't have the technological ability to create entanglement and manipulate it. And now we are doing that."

Physicists are in no doubt that things like entanglement are real — quantum mechanics definitely tells us something true about the world. But could the theory be incomplete? Could it be extended in a way that, while leaving us with a lot of weirdness, solves the measurement mystery? "There's been a lot of progress in ways of understanding the maths of quantum mechanics more directly," says Adrian Kent, a theoretical physicist at the University of Cambridge. "Not in the same way we understand classical mechanics — it's a different theory and it's much less intuitive because it describes a world we only experience indirectly. But we have a much clearer picture of how you map from the mathematics to what's going on in reality whether or not there's an observer or a measurement taking place. There are radical lines of thought out there on that. My own view would be that you need to supplement the [mathematics of quantum mechanics] with some extra variables. There has to be extra mathematical structure — certainly if you want to [apply quantum theory to the whole Universe]. This seems to be the most promising line of thought and is leading into interesting directions. That's my hunch."

But Kent recognises that he is holding a minority view. "[Changing the theory] would involve rewriting the last 100 years of physics, and that's a big ask," says David Wallace, a philosopher of physics at the University of Oxford. If we don't want to change the theory, and then perhaps we do need to concede that we as observers can influence reality. Find out more in the next article.

About this article

Sean Carroll is a physicist and cosmologist at the California Institute of Technology.

Adrian Kent is Professor of Quantum Physics in the Centre for Quantum Information and Foundations, DAMTP, University of Cambridge. He is currently working on a FQXi funded project developing a formulation of relativistic quantum theory in which simple additional mathematical postulates give us a description of a single real world consistent with cosmological observations and quantum experiments. He co-edited Many Worlds? Everett, Quantum Theory and Reality; one of his contributions to the volume was the question mark in the title.

David Wallace is a philosopher of physics at the University of Southern California, having previously received PhDs in physics and in philosophy at the University of Oxford. His 2012 book on the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, The Emergent Multiverse, was joint winner of the 2013 Lakatos Prize for philosophy of science.

Marianne Freiberger is Editor of Plus. She interviewed Carroll, Kent and Wallace at the 5th FQXi International Conference in Canada in August 2016.

This article is part of our Who's watching? The physics of observers project, run in collaboration with FQXi. Click here to see more articles and videos about questions to do with observers in physics.