Maths in space

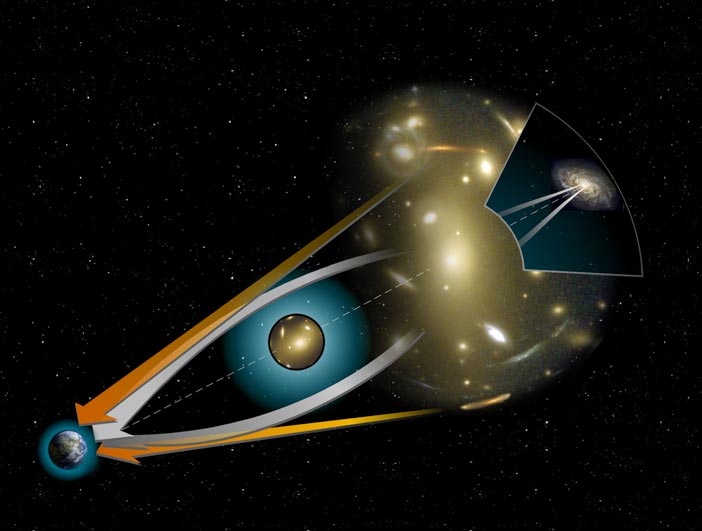

Bending light around a massive object from a distant source. The orange arrows show the apparent position of the background source. The white arrows show the path of the light from the true position of the source. From NASA.

Mathematicians working on one of the bedrocks of mathematics, the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra (FTA), have recently found collaborative allies in the unlikely field of astrophysics.

In their article From the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra to Astrophysics: A 'Harmonious' Path, in the Notices of the AMS, mathematicians Dmitry Khavinson from the University of South Florida, and Genevra Neumann from the University of Northern Iowa, describe their mathematical work that surprisingly led them to questions in astrophysics.

The FTA concerns the solutions of polynomial equations. A linear equation of the form\ $ ax+b=0 $ has exactly one solution. A quadratic equation like $ ax^2+bx+c=0 $ has two solutions:$$ x = \frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2-4ac}}{2a}. $$ These solutions are real if the part under the square root is positive, and coincide if this is zero. If the part under the square root is negative, then we have to evoke the world of complex numbers, which is equipped to cope with roots of negative numbers. A cubic equation like\ $ ax^3+bx^2+cx+d=0 $ has three possibly complex or coinciding solutions. The solutions to these types of equations are also called roots or zeros of the polynomial, and the FTA states that every polynomial of degree n has n roots.

The mathematicians were working on dynamical systems formed by polynomial equations like the ones above. These are systems which evolve over time within the complex space (for more on complex dynamics, read the Plus article A fat chance of chaos?) During the 1990s, Khavinson extended the FTA to polynomials of more than one variable. He proved that for a certain class of multivariate polynomials, known as harmonic polynomials, the number of zeros is at most $ 3n-2, $ where$ n $ is the highest power in the polynomial. Picking up on these results, Pietro Poggi-Corradini extended Khavinson's approach to rational harmonic functions — harmonic functions that can be written as that ratio of two polynomials: \ $$ f = \frac {P}{Q}. $$

The result of this work was slightly different — the number of zeros of rational harmonic functions turned out not to be less than $ 3n-2, $ but $ 5n-5. $ However, they drew no conclusions on whether this limit was "sharp" — that is, whether it could be pushed any lower. A week after publishing their results on arXiv, the researchers received a congratulatory e-mail from astrophysicist Jeffrey Rabin of the University of California, San Diego informing them that their theory resolved a gravitational lensing conjecture.

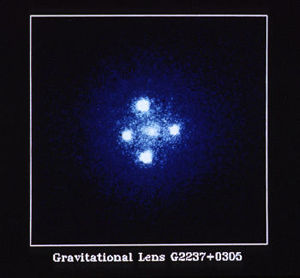

Multiple images are visible due to lensing. From NASA.

Gravitational lensing occurs when light from a very distant, bright source bends around a massive object (such as a cluster of galaxies) between the source object and the observer, and is one of the predictions of Einstein's general theory of relativity. Due to this deflection, the observer sees multiple images of the same source. If there is one massive star in between the source and the observer, the light gets bent around the star and we see what looks like two sources — sometimes the images can be merged and it will look like a ring. If there is more than one massive object between us and the source, what we see is more complex. The conjecture that the mathematicians solved was the Sun Hong Rhie conjecture which states that the number of images created by light bending around a massive object due to gravitational lensing is always less than $ 5n-5. $ Rhie initially found an arrangement of four massive objects that created 15 images, and then expanded this to the $ 5n-5 $ conjecture.

Having seen the results of Khavinson and Neumann, the astrophysicists were able to construct their results in terms of rational harmonic functions. Additionally, the mathematicians were able to use the results of the astrophysicists to prove that the $ 5n-5 $ bound was sharp. Who said pure maths has no physical application?