Hailstones revisited

"Mathematics is not yet ready for such problems." This is what the mathematician John Conway reportedly said about the Collatz conjecture, a simple-looking, yet unsolved mathematical mystery. This week Plus hosted two intrepid work experience students, Sabrina Qian and Joe Dickens, who decided to have a go at this fiendish problem nevertheless. And they made some intriguing discoveries. Here is what they came up with.

What are hailstone sequences and what's the Collatz conjecture?

Starting with any positive integer n, form a sequence in the following way:

- If n is even, divide by 2 to get a new number n'= n/2

- If n is odd, multiply by 3 and add 1 to get a new number n'=3n+1 .

n=10 gives the sequence

and n=25 gives the sequence

A sequence formed in this way is known as a hailstone sequence because the values bounce up and down just like a hailstone in a cloud.

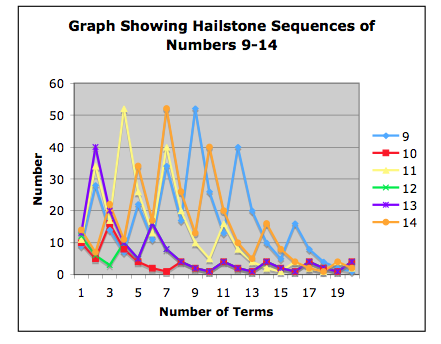

When you experiment with different values for n you will soon find that every hailstone sequence appears to end up with the cycle 4, 2, 1, 4, 2, 1... and so on. Below we've plotted a few sequences starting with different numbers.

But can it be proved that every starting value will generate a sequence that ends up with the cycle 4, 2, 1? This is the unsolved problem known as the Collatz conjecture — no-one has so far been able to prove it.

What can we prove?

There are, however, some things we can prove. First of all, we can prove that 4, 2, 1 is the only simple recurring pattern. A simple recurring pattern is one that only involves one odd number, so that the transformation 3n+1 is only used once. In the example 4, 2, 1 the only odd number is 1 and the only time 3n+1 is needed is to transform 1 into 4.

Suppose a simple recurring pattern contains the odd number n. Then 3n+1 must be a multiple of 2n. This is because you must be able to return to the number n starting from 3n+1 using only division by 2. In other words, we have:

where y is some positive integer.

Since y is a positive integer, the smallest it can be is 1. If y=1, then

3n+1=4n.

Solving this for n gives

This gives us the repeating pattern 1,4,2,1,4,2,... .

If we increase the value of y, so that y is at least 3, we get

so

Another thing that can be proved is that there are infinitely many numbers which, when "hailstoned", will produce the recurring pattern 4, 2, 1. In fact, any number n of the form

Curiosities

When trying to start working on the problem, we looked into many areas of it, hoping to find some clues to help us when we tried to work out other things. One of the first areas we looked at was how many terms of hailstoning it took for the sequence to reach its first 4. At first the number of terms seemed fairly random, when starting with 5 it took 3 terms, when starting with 6 it took 6 terms, when starting with 7 it took 14 terms and when starting with 8 it took only one term. However, after some time it became apparent that there were some curious links between numbers.

The first thing that we noticed was that after a while some doubles began to appear. Doubles was the term we used when two consecutive numbers took the same number of terms to produce their first 4. The first example of this was when we hailstoned 12 and 13, which both took 7 terms to reach their first 4. This was followed by 14 and 15, which both took 15 terms to reach their first four. Although the distribution of the doubles seemed random, they consistently appeared, and before long there were also triples, quadruples and even quintuples! Below is a list of all of the doubles, triples, quadruples and quintuples that we found when hailstoning the numbers 1 to 184.

Another curiosity is that all of the doubles consist of an even number followed by an odd number (rather than the other way around), and that most of the doubles seem to come in small groups. It also seems strange that there are more quintuples than quadruples — surely it seems more likely to have 4 in a row than to have 5 in a row? And finally, why are there so many doubles, triples, quadruples and quintuples? If they appeared occasionally, they could be passed off as coincidence, but the fact that there are so many indicate that there is some underlying mathematical explanation. If you know what that might be, why not leave a comment on the Plus blog?

Doubles

12 & 13 – 7 terms

14 & 15 – 15 terms

18 & 19 – 18 terms

20 & 21 – 5 terms

22 & 23 – 13 terms

34 & 35 – 11 terms

54 & 55 – 110 terms

60 & 61 – 17 terms

62 & 63 – 105 terms

76 & 77 – 20 terms

78 & 79 – 33 terms

82 & 83 – 108 terms

84 & 85 – 7 terms

86 & 87 – 38 terms

92 & 93 – 15 terms

94 & 95 – 103 terms

114 & 115 – 31 terms

116 & 117 – 18 terms

118 & 119 – 31 terms

140 & 141 – 13 terms

142 & 143 – 101 terms

148 & 149 – 21 terms

150 & 151 – 13 terms

162 & 163 – 21 terms

180 & 181 – 16 terms

182 & 183 – 91 terms

Triples

28, 29 & 30 – 16 terms

36, 37 & 38 – 19 terms

44, 45, & 46 – 14 terms

49, 50 & 51 – 22 terms

65, 66 & 67 – 25 terms

68, 69 & 70 – 12 terms

108, 109 & 110 – 111 terms

124, 125 & 126 – 106 terms

145, 146 & 147 – 114 terms

156, 157 & 158 – 34 terms

164, 165 & 166 – 109 terms

172, 173 & 174 – 29 terms

177, 178 & 179 – 29 terms

Quadruples

Quadruples are more rare than doubles, triples, and quintuples. The first quadruple is:

Quintuples

130, 131, 132, 133 & 134 – 26 terms

Further reading

The following website contains some other methods that could be used for proving the conjecture. They are not sufficient as a complete proof, but definitely worth trying out!

Comments

santanu.chakrabarti

"But can it be proved that every starting value will generate a sequence that ends up with the cycle 4, 2, 1?" --

Hi,

Can the proof be something in this line?

We have already proved that for any n=2^m the sequence ends up with the cycle 4, 2, 1. Now need to prove that for any sequence S(n), where n is the seed of the sequence, there exists a subsequence S(m) belonging to S(n) such that m=2^p for any integer p. If n is odd then the next number in sequence is 3n+1=2q for any integer q. q can be even or odd. If q is odd then the next to next of 3n+1 in sequence is 3q+1 which is again even. If q is even it can be either written as 2^x for some integer x, in which case we have reached our subsequence or it can be 2y for some integer y, in which case we need to again proceed as above.

Following this line of logic I think we could prove our subsequence statement above. Does it work?

Regards

Santanu

P.S: BTW why can't I post directly on the blog?

santanu.chakrabarti

Its me again.

Actually what I suspect is every Hailstone sequence has the subsequence 16, 8, 4, 2, 1 as its end.

Regards

Anonymous

I noticed a similar pattern, however, I took it out to 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1. Not every sequence ends with this pattern, however, as the numbers have to be large enough initially. It would be interesting to play around with though to determine if the pattern continues.

Sarah

Anonymous

Hello, I think you are onto something...

May I ask the problem in another way. Is Collatz conjecture analogous to this question: In the sequence

1,2,4,8,16,5,10,20 ... will this sequence actually meet every natural nubmer?

Looking forward to your answer mathematicians

Anonymous

Joe. The sequence 1,2,4,8,16,5,10,20 is not uniquely arrived at. 20 can only be reached from 40, but 40 can be reached from 80 or 13. Where there is a split possible, then both roads need to be taken into account. Then the conjecture is analogous.

Qualititatively it seems obvious that a hailstone sequence will eventually hit a value of 2^m. However, this is not a proof.

It would be interesting to see the "coverage" of numbers in hailstone sequences. eg

1 - 4 - 2 -1 covers the numbers 1,2, and 4.

3 - 10 - 5 -16 - 8 - 4 - 2 - 1 additionally covers 3,5,8,10, and 16.

7 - 22 - 11 - 34 -17 - 52 - 26 - 13 - 40 - 20 - 10... additionally covers 7,11,13,17,20,22,26,34,40 and 52

9 - 28 - 14 -7... additionally covers 9, 14, 28

I have deliberately omitted even numbers that reduce to already covered numbers and odd numbers that already appear in a hailstone sequence.

Anonymous

I have had another look at this and arrived at tthe following:

All even numbers will reduce eventually to an odd number. Hence we don't need to consider even numbers at all.

This leaves us with odd numbers. Odd numbers can be split into 2 types: 4n+1 and 4n-1.

The 4n+1 type has the following sequence

4n+1 --> 12n+4 --> 6n+2 --> 3n+1

This last number in the sequence is smaller than the first number - 4n+1 > 3n+1

So we can ignore 4n+1 numbers in our analysis because it will reduce to either another 4n+1 number (in which case it will reduce further) or it will reduce to a 4n-1 type.

Therefore the only types of odd number we need to consider are 4n-1 types.

eg 3, 7, 11, 15, etc.

I have some further analysis (eg 16m+7 always reduces when m is odd...), but I won't post just yet until I have more.

Anonymous

Hi

I've been thinking of something like this: if you can prove there is no other recurring pattern (of all kinds), it's obvious that any sequence ends up with 4,2,1 (eventually it will get to 4 and then it's stucked).

It's easy to prove there are no others positive recurring patterns length of 2,3,4 end even 5 numbers. I think that if you continue with this line you will maybe find the desirable proof :)

Anonymous

divide by two if it's an odd number

multiply by any odd number then add one

(the key is that you're adding 1, and that will inevitably reach a point whereby the number is 2 raised to some power)

Anonymous

I realized that if the hailstone sequences of two consecutive numbers took the same amount of steps to reach 4, then they must start coinciding (by this I mean that the sequences become the same) at some point. For any two consecutive numbers that do this, lets call them n and n+1, their sequences coincide after m steps. Therefore every consecutive two numbers of the form n,n+1 (mod 2^m) are a double. Also, if you remove every consecutive two numbers of the form 4n+1, 4n+2, the pattern might become clearer, because if 4n+1, 4n+2 is a double, then 3n+1, 3n+2 are.

Ball

The hailstone sequencing is the same problem as the Josephus problem in reverse. We want there to be a sequence that doesn't follow the formula but the sequencing eventually hits a binary number or a number made of binary numbers which then make the solution ..4, 2, 1. If you subtract the highest binary number you can see how the base number will react... For example 10 eventually sheds its 8 and becomes a 2 1 which is again the binary sequencing we don't want. What is the issue mostly is that no matter how high the number it still eventually hits a binary number which is antiprime and logs down to 421... So let's take a number like 7;

7=>22 => 11 =>34. 34 is 32 + 2 which are both binary... A few more logs and we will reach 4;2;1. 17=> 52 =>26 =>13 => 40...20...10...=>1. As soon as you hit a decimal multiple of 10 with just the 4..2..1 you are about to finish the series. To see how many moves are left you can count the binary parts; subtract the smaller from the larger and then subtract that product from the whole and multiply the former product to the latter and you have the steps. It works for 10 but probably not for others; just a thought but hopefully I helped in some fashion.

I'm Serious

0 doesn't end at 1

0 is an even number, so 0 divided by 2 is 0