How plants halt sands

Fighting the dune

Dwellers of arid areas have known for millennia that one way to stop the relentless advance of the desert is to plant plants that stabilise the shifting sand. However, this doesn't always work and many have seen their fields and woodlands devastated by desertification. The battle between vegetation and travelling sand dunes is an ancient one that has an enormous impact on people's livelihoods and on the global ecosystem. It's essential to understand the exact mechanisms behind this battle, especially in these times of changing climate. And this is what two physicists have just done for the first time.

Hans Herrmann, formally from the University of Stuttgart in Germany and now at the ETH in Zürich, Switzerland, has an impressive track record in studying migrating dunes. He combined forces with PhD student Orencio Durán, also from the University of Stuttgart. The two devised a mathematical model describing how and under what conditions a migrating dune, known as a barchan dune, can be turned by vegetation into an inactive parabolic dune, a dune that stays put. The dune behaviour predicted by their model fits well with what has been observed in nature and also gives a way of predicting who wins the battle in a given circumstance — plant or sand.

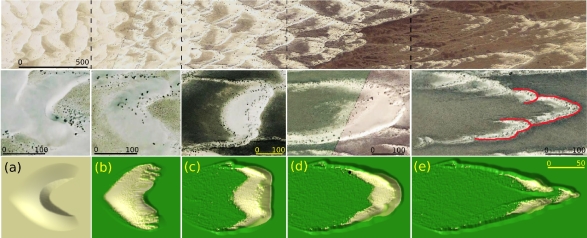

The top row shows a dune field in White Sand, New Mexico, developing from being vegetation-free and barchanoid on the left to a mixture of active and inactive parabolic dunes on the right. The middle row shows various types of dunes also found in White Sand. The bottom row shows the transition as predicted by the model.

Mathematical models of dynamical processes like dune migration usually consist of a system of differential equations. Just as the speed of a moving car is the derivative of distance travelled with respect to time, so other rates of change, such as the growth rate of a plant or the rate at which desert sand erodes, can be expressed by derivatives.

In this case, the model centres on a system of equations that captures the cyclical relationship between sand erosion, plant growth and the wind. Sand dunes migrate because the sand they are made of continually erodes. The erosion is caused by the wind whose impact is dampened by the shielding effect of vegetation, and that's why plants can play an important role in stopping dune migration. The growth rate of plants in turn depends on the rate at which the sand beneath them erodes, since even the hardiest of desert plants can't grow well if it hasn't got sufficient foothold or is continually covered over by sand.

With the help of their equations, the researchers were able to model the transition from active barchan to inactive parabolic dunes. They found that, in their model, the winner of the plant-sand battle is determined from the outset by one number alone: it's a ratio made up of the strength of the wind on the one hand, and, on the other, the initial size of the barchan dune together with the speed at which the plant can grow when unhampered by erosion. If this ratio, which is called the fixation index, is less than about a half, then erosion is no match for the plants' vigour and the dune will eventually halt. If it's bigger than a half, then erosion will overcome growth and the desert will win the day.

The scientists have not yet tested their model against reality, but preliminary comparisons with the behaviour of real dunes indicate that it may well prove accurate (see the image above). If it does, then it will play an important role in understanding our environment. "Our equations allow us to make long-term predictions over thousands of years about coastal dune evolution," says Herrmann, "and are therefore an important tool for coastal management. Concerning the environment, we can help protect semi-arid regions from desertification and even make predicitions about the evolution of biodiversity."

Further reading

- You can read the original article, Vegetation against dune mobility as published in The Physical Review Letters;

- To find out more about the science of dune migration, visit Hans Herrmann's webpage;

- You can read more about maths and nature's threats in Plus articles Tsunami, Going with the flow, When will they blow? and Quake-proof.