Particle hunting at the LHC: the standard model

CERN's Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is the world's largest laboratory experiment. It's a particle accelerator sitting about 100m below the Earth's surface, in a huge tunnel on the Franco-Swiss border. The experiment has smashed together tiny particles of matter in over a million billion collisions in the hope of finding answers to some deep questions about the way our Universe works. This article is about the theory behind the experiment, but you can also read brief introductions to the particles involved, the triumphant discovery of the Higgs boson and what other mysteries the LHC might solve.

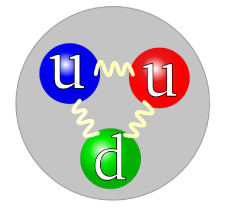

Protons are made up of quarks. Image courtesy Arpad Horvath.

The fragments of the collisions inside the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) give physicists hotly sought-after information about the tiniest constituents of matter, the fundamental particles. Protons are prime candidates for this experiment because of their electric charge: it's needed to accelerate the particles, so charge-less neutrons wouldn't do, and unlike electrons, which lose a lot of energy by x-ray emission, protons lose less energy as they are being accelerated.

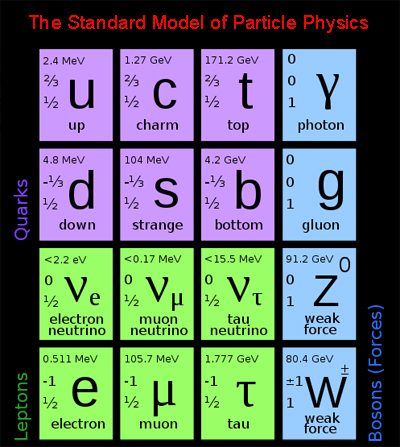

So far, smashing bits of matter together has helped physicists to compile a list of twelve fundamental particles that seem to make up the everyday matter that we see around us. The list includes electrons, but also particles called quarks, which make up protons, and which are held together by a sticky force called the strong nuclear force. There are other fundamental particles too, known as leptons and bosons. Besides the strong nuclear force and the familiar forces of gravity and electromagnetism, there is one more fundamental force, the weak nuclear force, which causes radioactive decay. The physical description of the fundamental particles, together with a mathematical description of how they behave, is known as the standard model of particle physics.

The fundamental particles of the standard model. Image MissMJ.

It turns out that when matter particles "feel a force", what is really happening on small distances is that particles are bumping in to each other. The electrostatic repulsive force between two electrons for instance, arises because one electron emits a photon, which then bumps into the other electron. Through conservation of momentum, this makes them fly apart a little. If we take into account that this process happens many times per second, then it appears as if the electrons feel the smooth form of repulsion that is familiar from physics in school. The standard model describes all known forces except gravity (which remains something of a mystery) in terms of the exchange of such particles. Particles of light, photons, carry electric and magnetic fields. The strong nuclear force in protons operates by exchanging particles called gluons.

The standard model, which was developed in the early 1970s, describes experiments with tremendous precision, in hundreds of different situations. But despite the amazing experimental success, there was a potentially fatal flaw in the theory: physicists had known for a long time that some fundamental particles have mass, but the mathematics underlying the standard model predicts that they should be massless. This false prediction is more than a minor error that's easily corrected: without the zero mass assumption the model just wouldn't work. A theoretical resolution to this puzzle came from a mechanism proposed in the 1960s by the physicist Peter Higgs (and others). Validating this theory, with the July 2012 announcement of the discovery of the Higgs boson, was a triumph of the first run of the LHC.

About the author

Ben Allanach is a Professor in Theoretical Physics at the Department of Theoretical Physics and Applied Mathematics at the University of Cambridge. His research focuses on discriminating different models of particle physics using LHC data. He worked at CERN as a research fellow and continues to visit frequently.