Plus Advent Calendar Door #6: The prime number theorem

The prime numbers are those integers that can only be divided by themselves and 1. The first seven are

$2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17.$

This is an illustration of the sieve of Eratosthenes, which is designed to catch prime numbers. You can find out more about the sieve here. Adapted from a figure by SKopp, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Every other positive integer can be written as a product of prime numbers in a unique way — for example $30=2\times 3\times 5 $ — so the prime numbers are like basic building blocks that other integers can be constructed from. This is why people find them interesting.

We have known for thousands of years that there are infinitely many prime numbers (see here for a proof), but there isn't a simple formula which tells us what they all are. Powerful computer algorithms have enabled us to find larger and larger primes, but we will never be able to write down all of them.

The prime number theorem tells us something about how the prime numbers are distributed among the other integers. It attempts to answer the question "given a positive integer $n$, how many integers up to and including $n$ are prime numbers"?

The prime number theorem doesn't answer this question precisely, but instead gives an approximation. Loosely speaking, it says that for large integers $n$, the expression $$\frac{n}{\ln{(n)}}$$ is a good estimate for the number of primes up to and including $n$, and that the estimate gets better as $n$ gets larger. Here $\ln{(n)}$ is the natural logarithm of $n$, which you can find on your calculator.

As an example, let's take $n=1,000$. The actual number of primes up to and including $1,000$ (which you can look up in this list) is $168$. Our estimate is

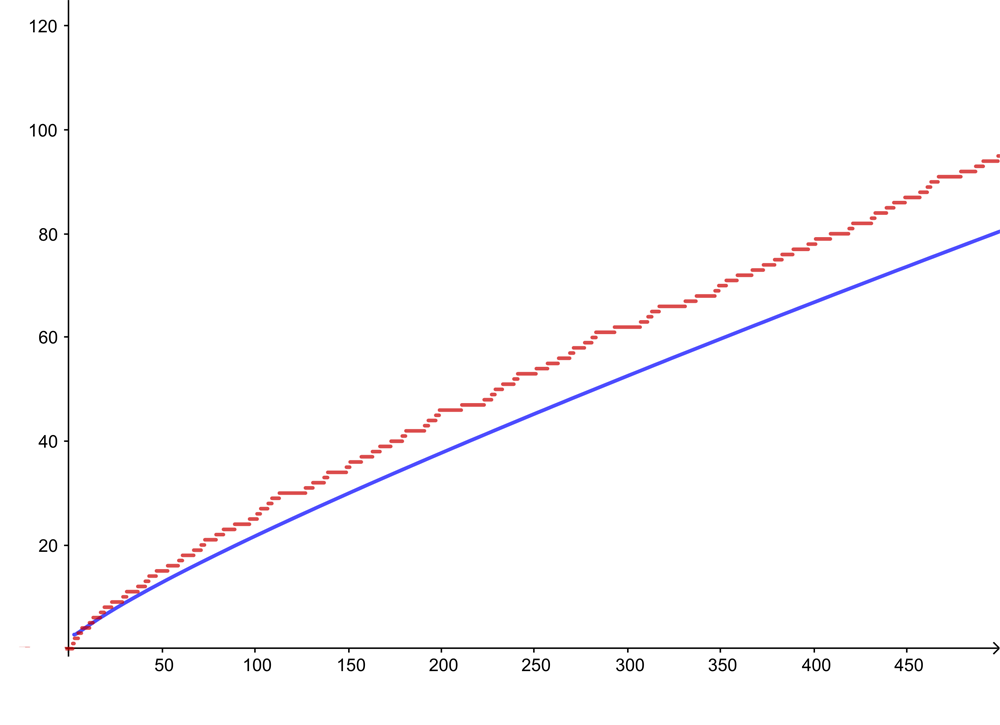

$$\frac{1,000}{\ln{(1,000)}} = \frac{1,000}{6.9}\approx 145,$$ which is a pretty good approximation. However, to be precise about what the prime number theorem tells us, we need to say what we mean by "a good estimate". The prime number theorem does not say that for large values of $n$ the difference between the true value and our approximation is close to $0.$ Instead, it tells us something about the question "what's the approximation as a percentage of the true value"? To go back to our example of $n=1,000$, the true value was $168$ and the approximation was $145$. Therefore, the approximation constitutes a proportion of $$\frac{145}{168}=0.86,$$ of the true result, which translates to 86\%. Not bad. For $n=100,000$ the actual number of primes up to and including $100,000$ is $9,592$, so that's the true value, and the estimate was $$\frac{100,000}{\ln{(100,000)}}=\frac{100,000}{11.5}\approx 8,686.$$ Therefore in this case the estimate constitutes a proportion of $$\frac{8,686}{9,592}=0.9,$$ of the true value. This translates to 90\%, so here the estimate is better than for $n=1,000$. Generally, the prime number theorem tells us that for large $n$ the approximation $n/\log{(n)}$ is nearly 100\% of the true value. In fact you can get it to be as close to 100\% as you like by choosing a large enough $n.$

The red curve shows the number of primes up to and including n, where n is measured on the horizontal axis. The blue curve gives the value of n/ln(n). The difference between true result and approximation increases as n grows, but the ratio between the two values tends to 1.

To state the prime number theorem in its full mathematical glory using mathematical notation, let's first write $\pi(n)$ for the number of primes that are smaller than, or equal to, $n$. The theorem says that \begin{equation}\lim_{n \to\infty} \frac{(n/\ln{(n)})}{\pi(n)} = 1.\end{equation} If you know a bit of calculus you will know that you can swap the numerator and denominator here, so expression (1) is equivalent to \begin{equation}\lim_{n \to\infty} \frac{\pi(n)}{(n/\ln{(n)})}= 1.\end{equation} The prime number theorem is usually stated using the second expression (2). It is also sometimes written as $$\frac{\pi(n)}{n/\ln{(n)}} \sim 1,$$ which in spoken language is "$\pi(n)$ is asymptotic to $n/\log{(n)}$ as $n$ tends to infinity."

Return to the Plus advent calendar 2021.

This article was produced as part of our collaboration with the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences (INI) – you can find all the content from the collaboration here.

The INI is an international research centre and our neighbour here on the University of Cambridge's maths campus. It attracts leading mathematical scientists from all over the world, and is open to all. Visit www.newton.ac.uk to find out more.