The Plus Olympic calendar: Monday 6th August

Yesterday was a great day for badminton with gold medals being awarded in the men's singles and doubles. This got us thinking about shuttlecocks. They are not like balls at all and this means that they don't behave like balls either. John D. Barrow, mathematician, cosmologist and prolific popular science writer, explains.

Shuttlecocks used for badminton are not like other projectiles found in sports. They are extremely asymmetrical, with a conical skirt about 6cm long and 6cm across that is attached to a cork of higher density at the narrow end of the cone. However, when the shuttlecock is hit it will quickly flip over so that the cork is leading because its pressure centre if different to its centre of mass. This will ensure that it is always approaching your opponent the right way round for her to hit it back.

The effect of hitting the shuttlecock is strange. When you hit a tennis ball or a cricket ball with a racquet or bat it goes further the harder you hit it. But no matter how hard you hit the shuttlecock it won't go much further than about 6 or 7 metres.

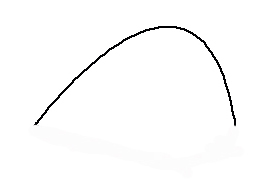

The trajectory of a shuttlecock, moving from left to right: it falls steeper than it rises.

The motion of the shuttlecock obeys Newton's laws of motion. Its acceleration is governed by the downward force of gravity and a drag force from the air that is proportional to the square of the shuttlecock's speed through the air. When it is first struck the shuttlecock is moving at its fastest and the drag force is therefore much bigger than gravity. So it moves upwards in a straight line, at an angle determined by the direction of impact from the racquet, gradually being decelerated by gravity. Eventually it is going so slowly that the force of gravity is comparable to the air drag force and the trajectory reaches a maximum height and curves downwards towards the ground. Gravity is now speeding it up and it quickly reaches a speed, termed the terminal speed, where the opposing forces of gravity (downwards) and air drag (upwards) become equal. There is now no net force on the shuttlecock and it moves downwards at this constant terminal speed, without experiencing any acceleration or deceleration. The overall trajectory doesn't look like a parabola: the shuttlecock falls steeper than it rises.

The terminal speed does not depend on the initial launch speed of the shuttlecock. It is determined by the strength of gravity, air density, the size and mass of the shuttlecock, and its smoothness. As a result it is these unchanging properties that fix the distance that the shuttlecock will reach when struck hard. Hitting it even harder can't make it go any further than these properties dictate.