Triangular number patterns

In this article we go hunting for triangular numbers. But we won't do this the usual way, by looking at triangles — oh no! Instead we find triangular numbers in the square grid of the multiplication table.

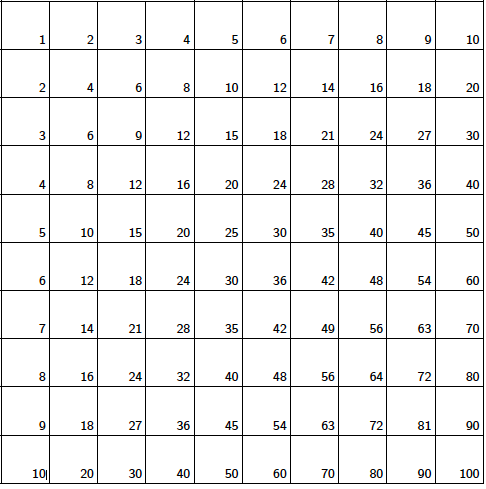

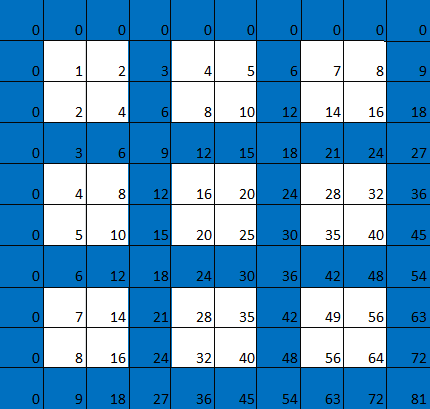

Before we explain what triangular numbers are, let's look at this multiplication table and what we can do with it. The table below contains the numbers 1 to 10 in the first row and the first column. Any other square contains the product of the first number in its row and the first number in its column.

We will add a row of 0s at the top and a column of 0s on the left. This still gives a consistent table and provides a nice frame for our patterns.

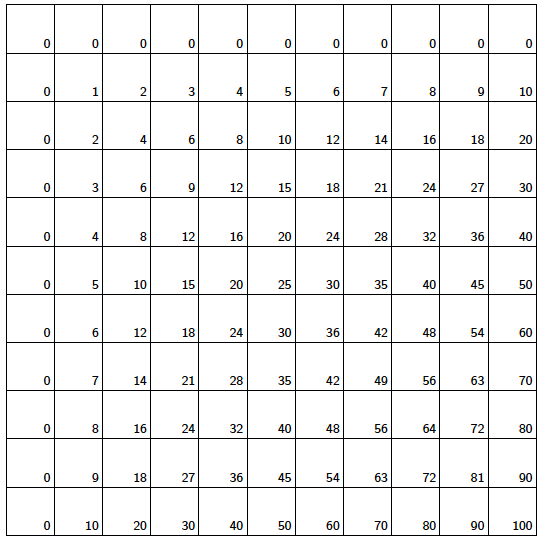

Now let's colour in blue all the squares with numbers that are multiples of 2 (even numbers). This means that all columns corresponding to multiples of 2 are blue and all rows corresponding to multiples are also blue, giving us a blue grid. Any square that is not in this grid remains white. (Here we have extended the table so that it runs until the number 16 in the horizontal and vertical directions.)

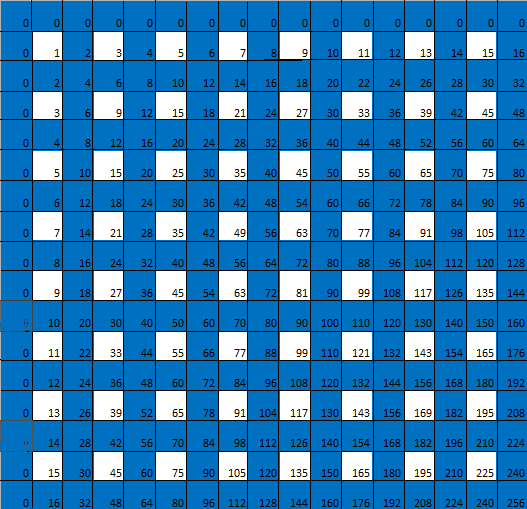

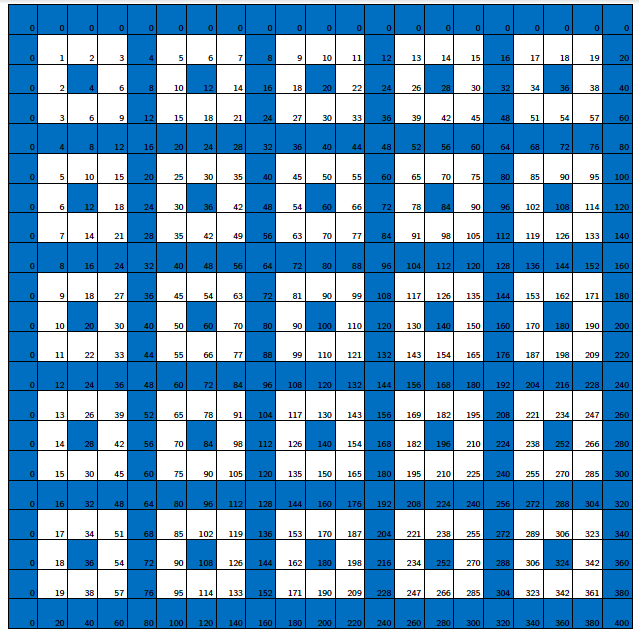

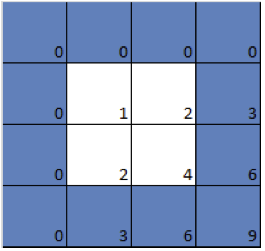

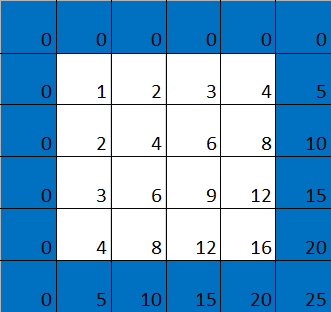

Now let's colour in blue all squares that are multiples of 3. As before, we get a blue grid consisting of the rows and columns corresponding to multiples of 3. The complement of this grid, that's the squares that are not part of it, form larger squares of 2x2=4 little squares:

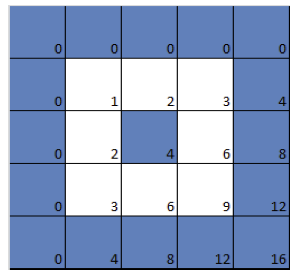

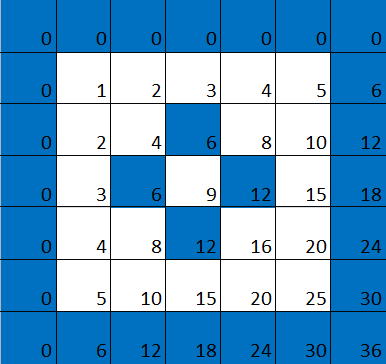

If we colour in blue all squares that are multiples of 4, we again get a blue grid. In this case the complement of the grid consists of larger squares containing 3x3=9 little squares each. In this case those large squares aren't entirely white, as the middle one in each is blue. The reason for this (as you might want to prove for yourself) is that 4 isn't a prime number.

Triangular numbers

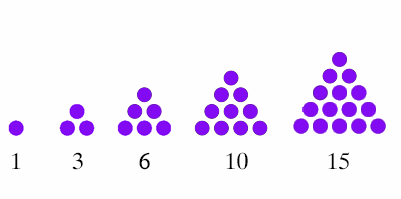

Let's see how triangular numbers come into the picture. A triangular number is a number that can be represented by a pattern of dots arranged in an equilateral triangle with the same number of dots on each side at equal distance from each other.

For example:

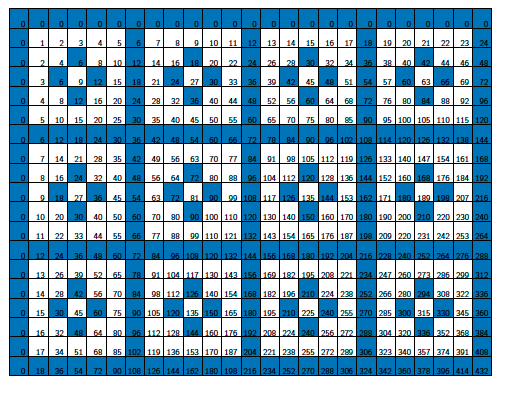

How can we possibly find these marvellous numbers within the square grid of the multiplication table? First, let's look again at the multiplication table in which squares corresponding to multiples of 3 are coloured blue. (We ignore the multiplication table which has multiples of 2 coloured blue because it's what mathematicians call trivial: boring and not particularly insightful). The first of the white squares in the coloured table for 3 looks like this:

Now let's look at the multiplication table in which squares corresponding to multiples of 4 are coloured blue. The first of the larger, mostly white squares looks like this:

Is this true in general?

Is this always the case, no matter what kind of multiples we colour blue? If yes, then the numbers within the first larger square of the multiplication table coloured for multiples of $k$ add to the square of the $(k-1)st$ triangular number $T__{k-1}.$ Let's see if this is true. Looking at only the first whole square we see that the first row consists of the numbers $$1,2,3,...,k-1.$$ The second row consists of those numbers multiplied by $2$: $$2,4,6,...,2(k-1).$$ The second row consists of the numbers in the first row multiplied by $3$: $$3,6,9,...,3(k-1).$$ The pattern continues in this way, row by row, until we get to the last row of the square. Here we have the numbers of the first row multiplied by $k-1$: $$k-1, 2(k-1), 3(k-1), ... ,(k-1)^2.$$ Adding the sums of the $k-1$ rows gives $$\begin{array}{cc} & 1+2+3+..+k-1 \\ + & 2(1+2+3+..+k-1)\\ + & 3(1+2+3+..+k-1)\\ & ...\\ + & (k-1)(1+2+3+..+k-1) \end{array}$$ Factoring out $1+2+3+...+k-1$, the sum becomes $$(1+2+3+...+k-1)(1+2+3+...+k-1)=(1+2+3+...+k-1)^2.$$ And since, as noted above, $$T_{k-1}=1+2+3+...+k-1,$$ we have shown that the numbers within the first larger square add to $T_{k-1}^2,$ the square of the $(k-1)st$ triangular number.Given that every square in the multiplication table is related to every other square (by multiplication or addition) it stands to reason that triangular also numbers feature in all of the other large squares in the complement of the blue grid. To find out if this is true, and continue our journey through the secrets of the multiplication table, see the next page...

About this article

Zoheir Barka, from Laghouat in Algeria, is an amateur and self-educated mathematician. He has a Masters degree in French language from Laghouat University and is currently a French teacher in elementary school.

Comments

Elisabeth S

A really interesting article, which I’m trying to get my head around.

Looking at the pattern is the sum

1 + 2 + 3 + 2 + 4 + 6 + 3 + 6 + 9 = 36 = (6)2 = T3 3 meant to read T2 3? Otherwise could you explain where the cubed part of the equation came from?

Thank you.

Marianne

Thank you very much for pointing this out, it was indeed a typo. We have fixed it now.