Career interview: Aerodynamicist

Christine Hogan graduated with a maths degree in 1991 from Trinity College, Dublin. She then embarked on a career as a computer programmer, system administrator and security consultant, working for start-ups, large companies, and as a self-employed consultant, in Europe and the US. In 1999 she started studying aerodynamics, with the intention of going into race-car design. Along the way, she has studied law, taught computer programming, and written a book on managing computer networking security.

Plus: When you were finishing school, what did you think you'd go on to do?

Christine: I was sure I wanted some kind of career in maths. I enjoyed maths so it seemed that if I worked all day every day just doing maths then this would be life in heaven. About the only such career I had heard of was actuarial work, and so I decided that was what I wanted to do.

I applied for jobs with actuarial companies as I was coming up to my Leaving Cert exams (Irish equivalent of A-levels) in 1987, but I also applied to go to university. I applied for a place to do a four-year maths degree at Trinity College Dublin, and was accepted.

Plus: Tell us about your maths degree.

Christine: It was a very different kind of maths to what I was doing in school, which I didn't expect. Maths at school was numbers, and I'm not sure I saw a single number in my whole four years in Trinity! I still liked it, but obviously I liked some subjects more than others. I did differential equations, calculus, and a lot of theoretical computing courses as well. I found those very interesting. Before I started my degree, I swore I would never do anything to do with computers, but in the end it was what I liked doing.

In the third year of my degree I started doing systems administration for the maths department, and then between my third and fourth year I got a job with a research group in the Computer Science Department doing some programming work. When I finished my degree, they offered me funding to do a Masters by Research with them. I was enjoying working with them and was interested by what I was doing, so I thought "Why not stay?". I started my research, on distributed object-oriented operating systems, in 1991.

Plus: What were you doing day to day?

Christine: I was programming and doing a certain amount of thinking and design. I understood a problem that I had and sometimes I would just go off and sit down with friends in the group, and we would talk over our problems - I would talk about my project for a bit, and we would talk about it and decide between all of us what seemed like the best approach and we'd all do that for each other's problems. Although, to be brutally honest, there was probably a lot more coffee and Guinness than there was research!

Plus: Did you spend all your time on your research?

Christine: Far from it! At the same time as doing my MSc, I carried on working as systems administrator for the maths department, as I had done as an undergraduate.

Plus: It sounds as if you really had your hands full ...

Christine: Well, that wasn't all. At the same time I was doing a night course in law.

Plus: Why law?!

Christine: Just because it was interesting. I was fascinated because it affects our lives all the time in so many ways and we don't even realise it.

Plus: Did all these extracurricular activities mean that you didn't have enough time to spend on your Masters?

Christine: Absolutely. That's why I spent two and a half years doing it. And I was still writing up for some time afterwards. Really I could have done a PhD in that time if I had given all my time to it.

Plus: So eventually you got enough material together to submit your Masters degree. Were you tempted to stay on and do a PhD?

Christine: Well, a little, but this was the beginning of 1994, and I had already spent two and a half years doing the Masters degree. Because everyone in the group did lots of outside work, some of the people doing PhD's had already been there for eight years and still hadn't completed. I couldn't cope with that, so I decided I had to get out.

I made a decision that I would only apply for jobs in hot places, because I was sick of the Irish weather, and I was offered a job in Sicily really quickly. I was systems administrator at a Research Centre specialising in oceanography and meteorology in a little tourist town called Erice, and actually I was cheated as far as the weather was concerned, because it was 700m above sea level and for a lot of the time was in the clouds. I stayed there from March to December 1994.

Plus: How come you stayed such a short time?

Christine: Well, before I had left Ireland I had applied for a Green Card to go and work in the US because there was a lottery visa programme that year and all you had to do was put your name and address on a postcard and send it off. After applying I pretty much forgot about it, but at the end of August 1994 I got a letter asking if I still wanted to go. By then I was bored in Sicily, and I knew some other Irish researchers who had recently gone to San Francisco, and they said "Come on over, it's fun". So I thought, why not? Back then there were lots of jobs going for programmers in the Bay Area.

Plus: How long did it take you to find something?

Christine: No time at all. I arrived on a Monday morning in January 1995, and being a laid-back European person, I thought I'd do nothing for the first few days, and then go to a social event on that Thursday arranged by one of the companies I had spoken to before leaving Ireland.

So I went to the event, and found that there was somebody waiting specifically for me, who whisked me into a room and started interviewing me, glass of wine in hand!

The next morning I got a phone call at 11 am saying that the company - Synopsys Electronic Design Automation Company - wanted to interview me, and could I be there at 1? They offered me a job on the spot, showed me around, and asked when I could start.

Plus: How long did you work there?

Christine: I worked in that contracting position for about five months and then I went permanent at the company. I was responsible for their computer security for about one and half years.

When I decided to leave, I spoke to some people from Synopsys who had left to form a consulting company. I ended up being employee number seven in October 1996. That was very interesting, working for so small a company. I worked for them for three years, in which time they grew to about forty people. Initially I was doing whatever needed doing, because in a very small company you can't really specialise, but over time I focused on computer security and networking. Then I moved into project management and customer management.

Plus: Tell us about your decision to return to Europe and study aerodynamics. It was a big step.

Christine: I had always had an interest in aerodynamics, primarily through being interested in Formula One racing. I liked the sport and I was intrigued by all the talk about the aerodynamics of the cars.

I had always thought it was a crazy interest of mine, not a serious career option. When I was finishing my maths degree I said to a friend "What I'd really like to do is work in Formula One as an aerodynamicist, but that's not really practical and so I'm going to do this Masters in Computer Science, there are lots of jobs in computer science." But all the time I was going to the Formula One races, and the first time a Formula One car went past me at speed it just took my breath away. In the end I knew I just had to get into this.

After some searching online Imperial College London appeared to be one of the best places to do aerodynamics, so I decided that was where I wanted to go. They ran a one-year Masters course, and I thought I would do that and decide whether I liked it, and if not it wouldn't be too late to change my mind.

I came to London in October 1999, and within about a day I knew I had made the right choice. So I talked to the Department about switching from the Masters course to doing a PhD and found one that was funded.

Plus: Tell us about your research.

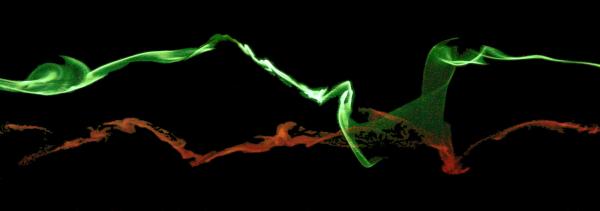

Christine: It's on aircraft wake vortices. These are extremely important because of landing patterns at airports. If you're landing a plane you have to leave a certain distance between you and the plane in front because of the aircraft wake. Two vortices come off the plane - this is what you see in the sky, the vortex wake from an aircraft. They are really high-speed winds going around in circles, like tornadoes. Following planes have to avoid those, or else they risk being tipped right over. The difference between flying high up in the sky and coming in to land is that the planes have to follow the same flight patterns.

This is why it's such a big deal. Everyone is following the same path and so they have to be a safe distance apart, because if you're coming in low to the ground and you suddenly get caught up in a vortex then you're dead, that's it, everyone on the plane is gone.

The separation distance depends on both the leading plane and the following plane. For example, a Cessna is more susceptible to being flipped over than something heavier. A 737 can deal with the wake when it's much stronger, so it can be much closer to the front plane. And of course something like the Cessna has almost no wake behind it - a following 737 won't even notice it.

Plus: How do you work on this problem?

Christine: I spend a lot of time using a wind tunnel and a water tank to do modelling. In the water tank we can visualise what the vortex looks like. So we can prototype a new shape in the water tank and decide whether it looks like the wake is breaking down more quickly or not. When I see something in the water tank that looks like a vortex is breaking down I take it into the wind tunnel, where we can use smoke and mirrors and a laser and camera to get wind velocities and speeds in vortices, and from that we can figure out what the force on the plane would be.

Onset of aircraft wake breakdown. The two wing-tip vortices are marked with different dye colours.

Plus: So you're not fulfilling your ambition of working on Formula One yet - when is this going to happen?

Christine: It's not an area that is often covered in PhD's. There was one PhD possibility that was about racing car wings and I wanted to do that but it didn't have any funding, so I couldn't. Then the project got part-funding from Ferrari, so now there's somebody in the office with me who is doing that project. I've now met the Ferrari people through him. He's a useful contact.

Plus: So what would you be doing if you get a job in Formula One?

Christine: I'd join a team. Each team has two drivers. There are probably something like three hundred people in a team in total. I don't know what a lot of them do, to be honest. Manufacturing these cars is a huge task, they're literally handmade. So are the models. You work on 40 to 50 percent scale models, made out of carbon fibre.

Each team has a group of aerodynamicists. Different teams work different ways. In some of them junior aerodynamicists are given a specific part of the car, say, the front wing, or the radiator inlets, or the brake cooling ducts. These things are chaotic problems though, so you're continually interacting with the rest of the team to check that what you do doesn't ruin what they're doing.

The connection with what I'm doing now is that one of the major issues with racing car design is controlling where the vortices shed by the car go. A friend who's now working for Reynard discovered that they had a problem with a vortex creating lift. You want to create downforce on these cars, so they stick to the track, but if they got the vortex going underneath the plate rather than above the plate, then they would get downforce rather than lift.

Plus: Have you managed to quell your appetite for extra-curricular work?

Christine: Not really! I've just finished co-authoring a book with an old colleague, Tom Limoncelli, called "The Practice of System and Network Administration" for Addison Wesley. It's just been published.

Plus wishes Christine all the very best in her new career.

About the author

Helen Joyce is an assistant editor of Plus.