Curious quaternions

John Baez is a mathematical physicist at the University of California, Riverside. He specialises in quantum gravity and n-categories, but describes himself as "interested in many other things too." His homepage is one of the most well-known maths/physics sites on the web, with his column, This Week's Finds in Mathematical Physics, particularly popular. In a two-part interview this issue and next, Helen Joyce, editor of Plus, talks to Baez about complex numbers and their younger cousins, the quaternions and octonions.

The birth of complex numbers

Like many concepts in mathematics, complex numbers first popped up far from their main current area of application. Baez explains that they had their genesis in Italian mathematics in the 1400s: "They wouldn't publish papers back then; if someone came up with a new method for solving polynomial equations they would keep it secret and throw out challenges and show they could whup the other people by solving equations that the other folks couldn't."

The birth of the complex

The particular challenge that brought mathematicians to consider what they soon called "imaginary numbers" involved attempts to solve equations of the type

ax2+bx+c=0.

To solve such an equation, you must take square roots, "and sometimes, if you're not careful, you take the square root of a negative number, and you've probably been repeatedly told never ever to do that. What some of these people noticed was that if you pretended you could take the square root of a negative number, and you went ahead and didn't blink, you could come out with the right answer. They had no idea what the negative square root was, but then later on in the calculation you might wind up squaring again and then you'd get an ordinary negative number. The negative square root would only show up in the intermediary steps in a calculation and so they were called imaginary numbers, because you didn't really know what they were but you could imagine that they made sense."

This trick of taking square roots of negative numbers and holding your breath until you squared again and the problem disappeared became familiar with time, but still no one had a clear idea of what these imaginary numbers actually were. The person who made the necessary conceptual breakthrough was the Irish mathematician William Rowan Hamilton.

The complex number with real part 1 and imaginary part 2

But this wasn't all Hamilton realised. The most impressive thing he managed to do is to work out what result you should get when you multiply two complex numbers. Baez uses an analogy with the geometry of the real numbers. "Take a number and multiply it by 2. What you're doing is making it stick out along the real number line twice as far away from the origin [0].

So multiplication is all about stretching or squashing, or even flipping over - if you multiply by -1 you're just flipping numbers over, which explains, by the way, why two negatives make a positive, because if you flip something over twice you get back to where you started! If you don't think of this using geometry it seems really mysterious."

Two negatives make a positive

And once Hamilton thought of complex numbers as points on the plane, he realised that he could think of multiplying by complex numbers as things you can do to the plane. "If you have a plane and you multiply by 2, you take any point on the plane and move it so that it's twice as far from the origin as it was but pointing the same direction. You can also multiply by 1/2: that's squashing down. But the fun happens when you start thinking about multiplying by one of these mysterious numbers, like $\sqrt{-1}$. That turns out to rotate the plane a quarter of a turn!

"The reason that's the right thing to do is that if you take something and rotate it by quarter of a turn and rotate it again then everything is pointing the opposite way to before. You've chopped the process of making something negative into two steps. You need this extra dimension to take the process of flipping things over and chop it into parts. If all you have is the real number line, there's no such thing as turning it around halfway.

"Multiplication is all about stretching or squashing, or even flipping over..."

Journey, destination unknown

So mathematicians had made a journey from wanting to solve equations to having a better understanding of the geometry of the plane - and when they set out on this journey they had no idea where they were going to end up. According to Baez, this happens a lot. "It started out as a trick, people got very used to the trick, still not understanding what it meant, and eventually they realised that complex numbers were just points in the plane. It wasn't sudden; it took a few hundred years to happen. And thinking about points in the plane as complex numbers, rather than just using their Cartesian coordinates, allows you to do something new: to multiply two of those points."

Baez keeps returning to multiplication as the important breakthrough. The way complex numbers are added is just the same as the way two vectors are added, or the way two points in Cartesian coordinates are added. So although it's good to know how to add two complex numbers, if this had been all Hamilton had thought of, no one would have been particularly impressed.

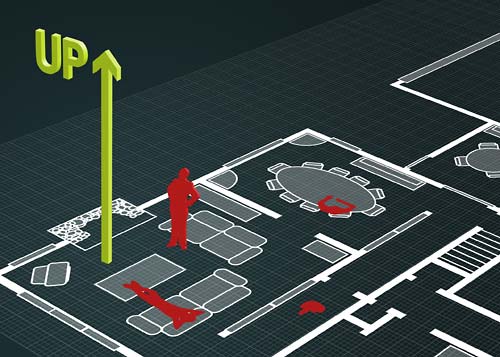

Delving deeper, Baez explains that the crucial thing is that complex numbers are lists of exactly two numbers; no more, no less. "Some of the things you learn to do with about Cartesian coordinates, or vectors, in the plane would work equally well in 3 or more dimensions. Addition, for example, works equally well in any dimension, for Cartesian coordinates, for vectors - it's sort of bland: 'go 2 feet east and 3 feet north, and then 2 more feet east and 5 feet north, and that's the same as having gone 4 feet east and 8 feet north.' That would work just as well if as well as east and north you also had 'up'.

The only way is up - addition works in three dimensions but what about multiplication?

"By contrast, what's really exciting about the complex numbers is that there are certain things you can do with a list of 2 numbers that you can't do with a list of 3 numbers, or a list of 4 numbers. There's a special way of multiplying lists of 2 numbers that's just as good as if you just multiply single numbers: the usual laws of arithmetic still work — in particular you can divide — and it has a nice geometrical meaning, but it turns out it wouldn't work in 3 dimensions. There wouldn't be any rule for taking lists of 3 numbers and multiplying them that would satisfy all the usual rules of arithmetic.

"Multiplication is very sneaky. You can only set up rules for multiplication that let you divide in dimensions 1, 2, 4 and 8. This is just a mysterious fact about the universe. Well, if you study maths it's not mysterious because you can see exactly why, but it's mysterious in the sense that when you hear about it first it just sounds completely crazy!

"You'll notice they keep doubling each time and that is an important part of the pattern, but you're left asking, why not 16? Well, people tried doing 16 and they know exactly why not. But to understand why, you really have to dig into the subject quite a bit."

You might wonder why it took so long to decide how to multiply two complex numbers - centuries since they had first been thought of. Why not just make up a rule? Why not just multiply the two real parts, and the two complex parts, which probably seems a lot more obvious a thing to do to many students when they first meet complex numbers? Baez explains that that just wasn't the way mathematicians thought in Hamilton's day. "He was the first one to realise that you could just make up a rule for how to multiply things. That [the way you suggest] makes a rule, and people do actually write papers about that kind of rule, and it has some good things about it.

"What you would like is that a bunch of the usual properties of multiplication that you're used to, still hold. One thing you know is that $x \times y$ is the same as $y \times x$, which is the case for the way of multiplying you suggest. And another is that $x(y+z)$ is the same as $xy+xz$. That still works too. But the main thing that's not nice about that way of multiplying is that, besides multiplying, you want to be able to divide, which is the opposite of multiplying. So once you have a rule about multiplying, you can ask is there a rule about dividing that goes along with it.

"With normal numbers you can divide by any number except zero. But with the ones that you just mentioned, there are lots of numbers you can't divide by, like (3,0) - having a zero in either slot is enough to put you off. With the standard way of multiplying complex numbers, the only number you have problems dividing by is (0,0)."

So what Hamilton was looking for - and what he found - was a rule for multiplying with only one number you can't divide by. And the main thing that was special was the relationship with rotations.

Too much is never enough

Perhaps predictably, Hamilton wasn't satisfied even with such a magnificent breakthrough. As soon as he had worked out how to multiply lists of 2 numbers - "couples", as he called them - he started looking for a way to multipy lists of 3 numbers, or "triplets". This quest consumed him. A long time later, he wrote a letter to his adult son in which he said:

Every morning in the early part of the above-cited month, on my coming down to breakfast, your (then) little brother William Edwin, and yourself, used to ask me, "Well, Papa, can you multiply triplets?" Whereto I was always obliged to reply, with a sad shake of the head: "No, I can only add and subtract them."Again it wasn't just any old rule Hamilton was after: he wanted a rule for multiplication that allowed him to divide by every number except zero. But effort isn't everything in mathematics, and it turns out that there is no such rule for triples. However, the intensive work paid off in an unexpected way. In an oft-commemorated mathematical "eureka moment", Hamilton finally realised that he could provide a multiplication rule for lists of 4 numbers that allowed him to divide. The moment came on 16th October 1843, when he was walking with his wife along the Royal Canal in Dublin, from Dunsink Observatory to the Royal Irish Academy. In Hamilton's own words:

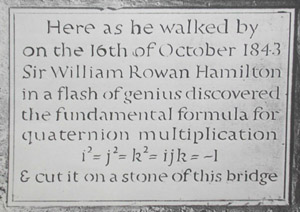

And here there dawned on me the notion that we must admit, in some sense, a fourth dimension of space for the purpose of calculating with triples ... An electric circuit seemed to close, and a spark flashed forth.In a famous act of mathematical vandalism, Hamilton carved the formula for multiplying what he later called quaternions into the wall of Broome Bridge, over the Canal. It read:

i2=j2=k2=ijk=-1.

The plaque to Hamilton at Broome Bridge. (Image from Hamilton Year 2005)

"I've been there recently," says Baez, "and the stone is very soft and covered with people carving their boyfriend's initials! I looked on the carvings to see if I could see any sign of Hamilton's original carving and I couldn't; it's completely covered with other carving and graffitti. There's a plaque there now though."

Hamilton's "in some sense" is revealing. He clearly felt that there was something strange about going into a fourth dimension when we normally think in a maximum of three, for obvious reasons. So what is this mysterious fourth dimension?

We pick up the story in the next issue of Plus...

To try your own hand at quaternion magic, try these three problems on our sister website NRICH:

Comments

Anonymous

Hamilton in his letter of 17 October 1843 to John Graves is very confused about the relationship between i, j, +1, and -1. He asks what are we to do with ij, when i and j are unequal roots of a common square. In fact there is no law of arithmetic which makes ij equal to anything but +1. It is these doubts of Hamilton which are the source of his fallacious theory of the non-commutative properties of the multiplication of imaginary numbers. All multiplication whether of real or imaginary numbers is commutative.

Anonymous

Another crackpot claiming well-established theories are "nonsense." Research Clifford algebras, will ya?

J

I can think of all kinds of non-commutative operations that have real world significance. Rotations are an easy example, all you have to do is spend a minute with a Rubik's cube and you'll see how rotation order matters. If you think rotation isn't combined with multiplication, remember complex numbers do just that, before commutativity is even a factor (no pun intended.)

In case you're having trouble with i and j being equal to the same sqrt(-1), here's a tip: define u^2=a and you can see that the inverse already has two values without leaving the reals. If you defined u=sqrt(a), that wouldn't be true. (If you explore the other solutions you'll eventually get to octonions, which don't even have associativity.)

Anonymous

Hamilton's quaternions equation i^2=j^2=k^2=ijk=-1 is incorrect because -1 like every other real, imaginary and complex number can only have two square roots so k^2 cannot equal -1 unless it also equals either i or j. However -1 does have three cube roots which are cos60+isin60, cos180+isin180 which equals -1, and cos300+isin300.

Marianne

The point is that the quaternions are an extemsion of the complex numbers - they are a larger set of numbers - just as the complex numbers are an extension of the real numbers. Within the set of real numbers -1 has no square root at all. Within the complex numbers -1 has two square roots. And within the quaternions -1 actually has infinitely many square roots. Hope that helps.

Anonymous

Most mathematicians have difficulty in calculating one value for k, let alone an infinity of quaternion values.

Paul Wolf

I have a different concept of the quaternion, as not necessarily involving complex numbers. A quaternion has four independent variables - one scalar and three vectors, which could also be vectors in real space. Hamilton was applying this to electromagnetics, which is where the imaginary numbers come in. But when he wrote about quaternions being a model for space-time (in 1843!), I think he was referring to vectors in real space.

Peter Cameron

Quaternion is 1 scalar, 2 vectors, and 1 bivector, components of the algebra of 2D space.

Octonion is 1 scalar, 3 vectors, 3 bivectors, and 1 trivector, components of the algebra of 3D space

Marcelo Ferraro Ribeiro

When I was 17 I tried hard to find a similar construction for complex numbers in 3d (in order to make fractals) and ´discovered´ the quaternions. I still think the way I devised them is more natural: It needs only two operators I^2=-1,J^2=-1, and the rule I J=-J I so, all multiplication for a +b I + c J + d I J follows. If you add another operator you get the octonions and so on.

Massy soedirman

I'm surprised to find a huge mistake at the very beginning of this article. Complex numbers were introduced by italian algebrists to make sense of their method to solve third degree equations who had real solutions but the formulas made use of square roots of negative real numbers. They were very reluctangly introduced (hence the terminology imaginary numbers) because at the end the result was a real numberIt is true that once you have real numbers they can appear as solution of quadratic equations but that is not the reason they were introduced.