The art gallery problem

The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao: hard to supervise. Image: MykReeve.

Sometimes a piece of mathematics can be so neat and elegant, it makes you want to shout "eureka!" even if you haven't produced it yourself. Often this happens when an ingenious shift in view point, a clever connection, or a new way of posing the question makes something tricky suddenly appear clear.

One of our favourite examples of this is the art gallery problem. It was first posed in 1973 by the mathematician Victor Klee. About five years later another mathematician, S. Fisk, came up with a very neat way of attacking the problem (after it had already been proved in a different way by Václav Chvátal). Let's start by setting the scene.

The problem

Suppose you have an art gallery containing priceless paintings and sculptures. You would like it to be supervised by security guards, and you want to employ enough of them so that at any one time the guards can between them oversee the whole gallery. How many guards will you need?

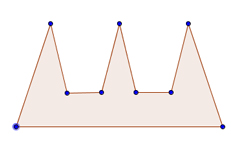

A simple polygon with nine vertices.

Ordinary buildings tend to be rectangular, of course, but art galleries can have all sorts of crazy shapes, so it's hard to find a general answer. To make things a little easier, let's assume that the floor plan of the gallery is a simple polygon: a shape that is bounded by straight line segments that do not cross each other, and which doesn't contain any holes. Let's also assume, as is often the case in real galleries, that the guards don't move around and are placed in the corners, or vertices, of this polygon.

It's intuitively clear that the number of guards needed will depend on the number of vertices of the polygon. A polygonal gallery with many vertices can contain lots of little niches that will need their own guard, as guards placed elsewhere can't see inside them. Let's write n for the number of vertices in the polygon (so n=9 in the example in the figure). Fisk's clever argument shows that to guard a gallery with the shape of a simple polygon with n vertices you never need more than n/3 guards (so that's 9/3 = 3 guards in the example in the figure). That's true for any simple polygon with n vertices, no matter how complicated and irregular it looks.

The proof

A guard can see a particular point p inside the gallery if there is no wall in between. In our picture this corresponds to the condition that the straight line that connects the guard's vertex and the point p lies entirely inside the polygon, not crossing any of its edges (which correspond to the walls). If we can chop the polygon into regions, each of which can be overseen by a single guard placed at a vertex, then we have found a placement of guards that can together oversee the whole polygon.

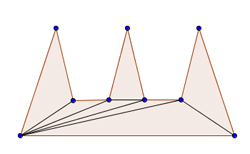

One method for dividing a polygon into regions is to triangulate it: connect the vertices of your polygon by straight lines in such a way that the polygon is divided up into triangles. Any simple polygon can be triangulated.

A triangulation of the simple polygon.

Clearly, a guard placed at the vertex of a triangle (which is also a vertex of the polygon) can oversee the whole triangle. This is because a triangle is a convex shape: the straight line connecting any two points in the triangle is entirely contained within the triangle. So if we place a guard at a vertex of each triangle then our problem is solved. Each guard will oversee the corresponding triangle, and since the triangles together cover the whole polygon, we have ensured that the whole polygon is guarded.

The picture we are now looking at is of a triangulated polygon. But we can think of it in a different way. The shape is also what mathematicians call a graph: a collection of vertices (the vertices of the triangles) connected by lines, called edges. Graph theorists are very fond of colouring problems, which involve colouring the vertices or edges in a graph in a way that satisfies particular properties. Fisk's clever trick was to transform the guard problem into such a colouring problem.

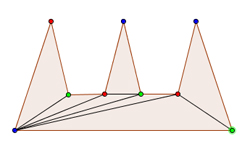

A vertex colouring of the graph.

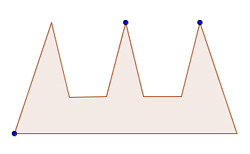

Let's try and colour the vertices using three different colours so that every individual triangle has no two vertices coloured in the same colour. Next, choose a particular colour, say blue, and place a guard at each vertex coloured in that colour. Since every triangle has exactly one blue vertex, this gives us one guard for each triangle, so this placement of guards makes sure they can together see the whole gallery.

But how many guards does this require? The colouring partitions the collection of vertices into three groups; one for each colour. Since we are trying to minimise the number of guards, we are interested in the smallest of these three groups. A bit of thought will convince you that this smallest group will never contain more than n/3 vertices. So we will never need more than n/3 guards to supervise the gallery.

Three guards placed at the blue vertices can together oversee the whole gallery.

Et voilà, we have derived Fisk's answer! The only step we have left out here is the question of whether any triangulation can be coloured with three colours so that no two vertices in one triangle have the same colour. But it is not too hard to prove that the answer is yes (see here).

Onwards an upwards

Another great thing about the art gallery problem is that it offers a number of new avenues to explore. What if the guards are not confined to the corners of the gallery? What if they are allowed to move around? What if there are obstacles in the middle of the gallery that you cannot see through? Or the walls are curved? And what if, instead of guarding a two-dimensional polygon, you are trying to guard a three-dimensional polyhedron? You could also consider a different set-up, not looking at guards inside a gallery, but at guards outside a prison guarding its walls. Mathematicians have found answers to some of these questions (see here), though some proofs have turned out to be quite hard. There is still much to explore, however, and we are looking forward to more beautiful proofs.

About the author

Marianne Freiberger is Editor of Plus.

About this article

This article was inspired by content on our sister site Wild Maths, which encourages students to explore maths beyond the classroom and designed to nurture mathematical creativity. The site is aimed at 7 to 16 year-olds, but open to all. It provides games, investigations, stories and spaces to explore, where discoveries are to be made. Some have starting points, some a big question and others offer you a free space to investigate.

Comments

Anonymous

A lovely description! Fisk's is certainly the proof 'from the book' but Václav Chvátal perhaps deserves a mention as the first person to answer Klee's question? See http://www.theoremoftheday.org/Theorems.html#198

Marianne

Fair enough! We have included Chvátal.

Anonymous (really Dennis Geller, but no need to print)

Art galleries as described in the article (as triangulations of polygons with some interior lines missing, the interior lines being added as part of the proof) are outerplanar. An earlier proof that the chromatic number of an outerplanar graph is at most three -- and that a triangulation of a polygon not only has chromatic number three but that there is only one way (except for interchange of color names) to achieve such a coloring -- was given by Chartrand and Geller, and appears as an exercise in Frank Harary's textbook (page 149).