The PEMDAS Paradox

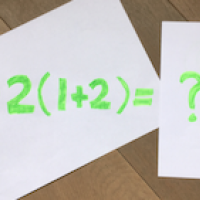

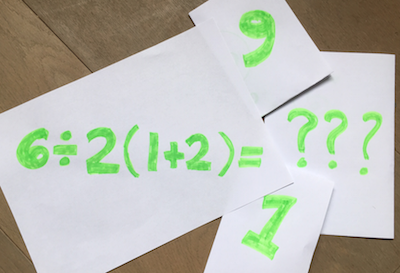

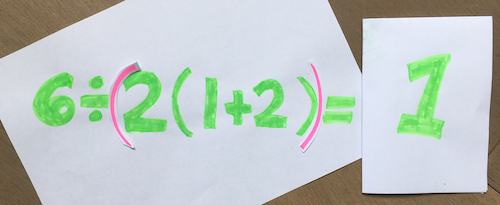

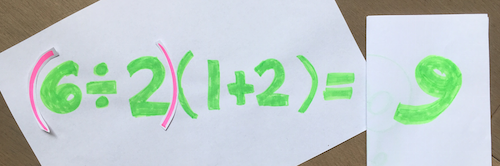

It looks trivial but it keeps going viral. What answer do you get when you calculate $6\div 2(1+2)$? This question has reached every corner of social media, and has had millions of people respond with two common answers: $1$ and $9$.

You might think one half of those people are right and the other half need to check their arithmetic. But it never plays out like that; respondents on both sides defend their answers with confidence. There have been no formal mathematical publications about the problem, but a growing number of mathematicians can explain what's going on: $6\div 2(1+2)$ is not a well-defined expression.

Well-defined is an important term in maths. It essentially means that a certain input always yields the same output. All maths teachers agree that $6\div (2(1+2)) = 1$, and that $(6\div 2)(1+2) = 9$. The extra parentheses (brackets) remove the ambiguity and those expressions are well-defined. Most other viral maths problems, such as $9-3\div 1/3 + 1$ (see here), are well-defined, with one correct answer and one (or more) common erroneous answer(s). But calculating the value of the expression $6\div 2(1+2)$ is a matter of convention. Neither answer, $1$ nor $9$, is wrong; it depends on what you learned from your maths teacher.

The order in which to perform mathematical operations is given by the various mnemonics PEMDAS, BODMAS, BIDMAS and BEDMAS:

- P (or B): first calculate the value of expressions inside any parentheses (brackets);

- E (or O or I): next calculate any exponents (orders/indices);

- MD (or DM): next carry out any multiplications and divisions, working from left to right;

- AS: and finally carry out any additions and subtractions, working from left to right.

Two slightly different interpretations of PEMDAS (or BODMAS, etc) have been taught around the world, and the PEMDAS Paradox highlights their difference. Both sides are substantially popular and there is currently no standard for the convention worldwide. So you can stop that Twitter discussion and rest assured that each of you might be correctly remembering what you were taught – it's just that you were taught differently.

The two sides

Mechanically, the people on the "9" side – such as in the most popular YouTube video on this question – tend to calculate $6\div 2(1+2) = 6 \div 2 \times 3 = 3\times 3 = 9$, or perhaps they write it as $6\div 2(1+2) = 6\div 2(3) = 3(3) = 9$. People on this side tend to say that $a(b)$ can be replaced with $a\times b$ at any time. It can be reduced down to that: the teaching that "$a(b)$ is always interchangeable with $a\times b$" determines the PEMDAS Paradox's answer to be $9$.

On the "1" side, some people calculate $6\div 2(1+2) = 6\div 2(3) = 6\div 6 = 1$, while others point out the distributive property, $6\div 2(1+2) = 6\div (2+4) = 6\div 6 = 1$. The driving principle on this side is that implied multiplication via juxtaposition takes priority. This has been taught in maths classrooms around the world and is also a stated convention in some programming contexts. So here, the teaching that "$a(b)$ is always interchangeable with $(ab)$" determines the PEMDAS Paradox answer to be $1$.

Mathematically, it's inconsistent to simultaneously believe that $a(b)$ is interchangeable with $a\times b$ and also that $a(b)$ is interchangeable with $(ab)$. Because then it follows that $1 = 9$ via the arguments in the preceding paragraphs. Arriving at that contradiction is logical, simply illustrating that we can't have both answers. It also illuminates the fact that neither of those interpretations are inherent to PEMDAS. Both are subtle additional rules which decide what to do with syntax oddities such as $6\div 2(1+2)$, and so, accepting neither of them yields the formal mathematical conclusion that $6\div 2(1+2)$ is not well-defined. This is also why you can't "correct" each other in a satisfying way: your methods are logically incompatible.

So the disagreement distills down to this: Does it feel like $a(b)$ should always be interchangeable with $a\times b$? Or does it feel like $a(b)$ should always be interchangeable with $(ab)$? You can't say both.

(Image from Quora)

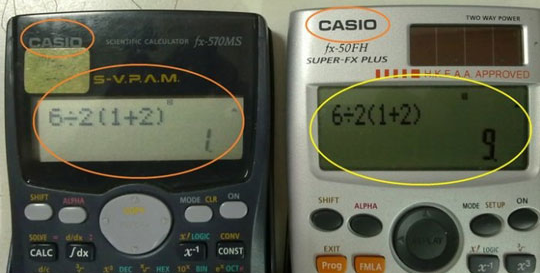

In practice, many mathematicians and scientists respond to the problem by saying "unclear syntax, needs more parentheses", and explain why it's ambiguous, which is essentially the correct answer. An infamous picture shows two different Casio calculators side-by-side given the input $6\div 2(1+2)$ and showing the two different answers. Though "syntax error" would arguably be the best answer a calculator should give for this problem, it's unsurprising that they try to reconcile the ambiguity, and that's ok. But for us humans, upon noting both conventions are followed by large slices of the world, we must conclude that $6\div 2(1+2)$ is currently not well-defined.

Support for both sides

It's a fact that Google, Wolfram, and many pocket calculators give the answer of 9. Calculators' answers here are of course determined by their input methods. Calculators obviously aren't the best judges for the PEMDAS Paradox. They simply reflect the current disagreement on the problem: calculator programmers are largely aware of this exact problem and already know that it's not standardised worldwide, so if maths teachers all unified on an answer, then those programmers would follow.

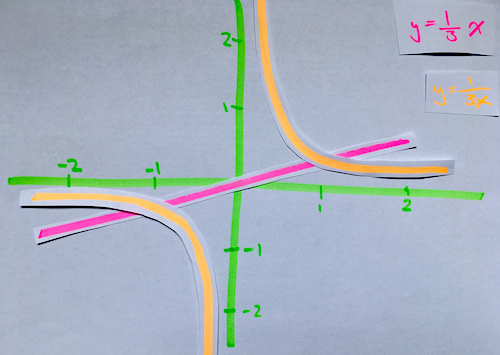

Consider Wolfram Alpha, the website that provides an answer engine (like a search engine, but rather than provide links to webpages, it provides answers to queries, particularly maths queries). It interprets $6\div 2(1+2)$ as $9$, interprets $6\div 2x$ as $3x$, and interprets $y=1/3x$ as the line through the origin with slope one-third. All three are consistent with each other in a programming sense, but the latter two feel odd to many observers. Typically if someone jots down $1/3x$, they mean $\frac{1}{3x}$, and if they meant to say $\frac{1}{3}x$, they would have written $x/3$.

In contrast, input $y=\sin 3x$ into Wolfram Alpha and it yields the sinusoid $y=\sin (3x)$, rather than the line through the origin with slope $\sin 3$. This example deviates from the previous examples regarding the rule "$3x$ is interchangeable with $3\times x$", in favor of better capturing the obvious intent of the input. Wolfram is just an algorithm feebly trying to figure out the meaning of its sensory inputs. Kinda like our brains. Anyway, the input of $6/x3$ gets interpreted as "six over $x$ cubed", so clearly Wolfram is not the authority on rectifying ugly syntax.

On the "1" side, a recent excellent video by Jenni Gorham, a maths tutor with a degree in Physics, explains several real-world examples supporting that interpretation. She points out numerous occasions in which scientists write $a/bc$ to mean $\frac{a}{bc}$ . Indeed, you'll find abundant examples of this in chemistry, physics and maths textbooks. Ms. Gorham and I have corresponded about the PEMDAS Paradox and she endorses formally calling the problem not well-defined, while also pointing out the need for a consensus convention for the sake of calculator programming. She argues the consensus answer should be 1 since the precedence of implied multiplication by juxtaposition has been the convention in most of the world in these formal contexts.

The big picture

It should be pointed out that conventions don't need to be unified. If two of my students argued over whether the least natural number is 0 or 1, I wouldn’t call either of them wrong, nor would I take issue with the lack of worldwide consensus on the matter. Wolfram knows the convention is split between two answers, and life goes on. If everyone who cares simply learns that the PEMDAS Paradox also has two popular answers (and thus itself is not a well-defined maths question), then that should be satisfactory.

Hopefully, after reading this article, it's satisfying to understand how a problem that looks so basic has uniquely lingered. In real life you should use more parentheses and avoid ambiguity. And hopefully it’s not too troubling that maths teachers worldwide appear to be split on this convention, as that’s not very rare and not really problematic, except maybe to calculator programmers.

For readers not fully satisfied with the depth of this article, perhaps my previous much longer paper won't disappoint. It goes further into detail justifying the formalities of the logical consistency of the two methods, as well as the problem's history and my experience with it.

About the author

David Linkletter

David Linkletter is a graduate student working on a PhD in Pure Mathematics at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, in the USA. His research is in set theory - large cardinals. He also teaches undergraduate classes at UNLV; his favourite class to teach is Discrete Maths.

Comments

Evans S.

The problem is that many people "glue" 2 and (2+1) together, treating it as a unity and in that way putting their relationship, in terms of priority, before the commonly accepted order of operation.

In other words, they don't treat it as:

' something...2*(2+1) ' ,

but as

' something...[2*(2+1)] ' ,

which causes the problem here.

You can't just, out of nowhere, look at '2' and '(1+2)', ignoring the relationship in which '6' is with '2', and use left-distributive property here, because you go out of the order of operations.

I think it's commonly accepted that 'xy' means 'x*y' and should be treated as such, followed by treating operation of division and multiplication with equal priority, going from left to right.

If you assume otherwise and put the priority of multiplication, even with omitted * sign, before the other operations, then you are actually and indeed making a small mistake here, assuming something that is out of convention.

So, I think that '9' is indeed the correct answer and the other way of thinking IS NOT equivalent - maybe not in obvious way, but it's disregarding the order of operations and treats unmarked 'xy' multiplication not as 'x*y', but as '(x*y)' , discretely "adding brackets"!! :-)

Slavic

It should be written like 6*(1+2)/2

J

People aren't "out of nowhere" gluing these together. Omitting the operator generally means that you should consider the multiplied numbers as one term. Let's change what's in the parentheses to simply "x". The problem now is 6 / 2x. Many people looking at this expression will consider 2x as one term. So they will read it as 6 / (2x), not (6/2)*x. That's the main reason why some people are in the 1-camp. No operator implies the multiplication already happened and should be taken as such as one term. Frankly it's a poorly written expression, as explained in the article.

Sam

Is 6÷2x or 6/2x where x=3 equal to 9 or 1? These are the same question. When there is a variable written like this most people attach it to the coefficient that directly proceeds it, and would consider it to be 6/(2x) or 1.

Gary

Statment

6÷2×=6 X=3

6÷2times3 =? Not (2×)

Use pemdas in order

6÷2=3 3×3=6 6=6 not 6÷6=1

Anonymous

6/2(x)=6

According to pemdas logic

6/2= 3

3 times x = 6

3(x)=6

X= 2

NO!!!!!

6/2(x)=6

2(x)= 1

X=1/2

Yes!!!!

You’re all welcome

Trakfres

I remember the P in PEMDAS meant to do Parenthesis/Groupings until they disappeared. Was no one else told this?

James Bowater

I have stopped teaching my students BEDMAS (or it's equivalents) as it is misleading in so many ways.

I now use GEMA.

One: I don't like the idea of a large MAS in someones BED!

Two: GEMA is such a lovely name.

Three: the DM (or MD) and the AS (or SA) misleads so many students.

G=Grouping

E= Exponents

M=Multiplication(and division is just inverse multiplication)

A= Addition (and subtraction is just inverse addition)

It is time we put PEDMAS, BIDMAS, BOMDAS, etc to BED and woke up with GEMA

Marvin Moran

I agree with GEMA, because it is much less misleading given that there are only 4 steps in the order of operations, but stick to the math and please do not associate a good idea with woke ideology!

Adam Jones

I would argue that there is no answer because it is not written in any standardized form of mathematics. There is a reason why no math teacher on earth would accept this as an equation, it is ambiguous. Unlike languages that can over time due to the common use of a term or word by common people, see the Oxford dictionary's inclusion of slang like ain't, mathematical notation can only change by the agreement of scholars. Those that shout PEMAS as the answer need to learn math beyond the 4th grade. When math is used for a purpose, such as engineering, it needs to be clear and unambiguous. Proper notation allows for the identification of units of measure. We don't use "slang" math notation for a reason if it isn't agreed upon than it can become useless.

Charlotte

The way I see it, if there is no 'multiply' sign between the 2 and the (1+2), it acts just like if you were to have the expression 6/2x. Naturally, if x is replaced by (1+2), or (3), 2x=6, so the answer would be 1, as 6/6=1.

Dee

If you take 6/2x a step further, it's 2x/2x, since you can factor out the "6," to 2(1+2) & replace what's inside the parentheses with the variable "x." The term"2x" is a monomial, which never needs parentheses around it because a monomial is one term with a single value of the PRODUCT of the coefficient & the variable -- like saying "2 dozen," which everyone understands holds the value of 24.

Given that "x" does not equal zero, the monomial division of 2x divided by 2x (correctly written as 2x/2x or as 2x over 2x) always equals 1, because the like variables (the "x's") cancel out, leaving 2/2=1.

When x=(1+2), then 2x=6, so 2x/2x=6/6=1.

Andy Boy

In my view, this entire article is unnecessary. Unless I'm wrong, you always solve within parenthesis first, then reset, so to speak, and go about the problem from the beginning, which in this case would place the mathematician back at the division portion. From there, you have a simple problem resembling 6/2*3=9. And you would solve it left to right to come up with the obvious answer that any online calculator I've tried comes up with; 9. Was this posted on April 1st as some elaborate joke? This is obviously 9, unless there are multiple versions of the rule of the order of operations.

Pumpkin1

Unfortunately, I see it as being unnecessary in the opposite direction. Unless we have given up on the distributive method, the only way to resolve the parentheses is to expand the multiplier of 2 across the contents of the parentheses. Putting a "6/" in front of 2(2+1) does not mean that the first 2 no longer gets distributed.

Shim

The entire term outside of parentheses needs to be distributed to use distributive property

6/2(2+1)

12/4+6/2

3+6

9

Doug

Where it says “solve within parentheses first”

6/2(1+2) solve inside parentheses first

6/2(3) simplify parentheses last

6/6

Answer is 1

It doesn’t say “solve inside parentheses.”

It states “first”.

George Nalugala

I have spent 4 months arguing, (especially with Americans) over this matter, because they were taught differently, and in my opinion, wrongly.

At the crux of this matter are two principles that are ignored by many:

1. That multiplication is commutative, always.

2. That division is not commutative, and is only partly distributive.

Therefore, a rational person must ask themselves: when I find a math problem that involves both division and multiplication, how do I approach it, in order to retain the full power of the principles above?

Do I enter then shut the door, or do I shut the door then enter?

Do I reproduce then die, or do I die then reproduce?

That level of logic is what is missing.

Multiplication allows you (by commutation), to "walk in or out" as you wish. It allows you to "reproduce" early or late, for as long as you are alive. Once you divide, commutativity is lost (like death - reproduction is impossible afterwards).

Division, on the other hand, shuts the door; or is like the event of death. Once the door is shut, you cannot enter or leave. Once one is dead, they cannot reproduce!

How does this apply here?

Suppose we have 6 ÷ 2(2+1).

We cannot start with division, simply because it BLOCKS multiplication from being commutative.

You see, clearly, 2*(2+1) = (2+1)*2 and that MUST always remain valid and feasible. We cannot prefer or apply any method that denies this principle. This should be self explanatory.

Anyone who suggests anything that denies the commutativity of multiplication opposes math itself!

So, 6 ÷ 2(2+1) can only be resolved by safeguarding the commutativity of multiplication, before we "shut the door."

That is why 6 ÷ 2(3) = 6 ÷ 6 = 1, and not 9.

We cannot ever decide to die first, then start wondering whether reproduction is possible!

Matt678

Multiplication is commutative. a * b = b * a. The problem is how you define your variables. You assume that a = 2 and b = 3, independently of the division. The reality is, a = 6 / 2 = 3 because of PEMDAS rules. Then you have 3 * 3 (a * b) = 3 * 3 (b * a) = 9.

You can't just ignore the division and do commutation on the multiplication by itself. There's no such thing as "shutting the door", whatever that means.

Anonymous

Parenthesis must be solved First according to PEDMAS.

6÷2(2+1)=6÷2(3)=6÷6=1.

André

6÷2(2+1)=6÷2(3)=6÷2*3=9

Doug

By what rule can you convert

6/2(3) to 6/2*3.

Does 3x/3x = 1 or x²

2(3) is not equal to 6*3

Kyle

I remember getting problems wrong all the time because I dident simplify in my shown work. When you solve for what is in the parentheses 6/2(1+2) you get 6/2(3) and then you have solved for what's in the parentheses already. That's done, you did you P in PEMDAS. And so 2(3) just becomes 2×3 at that point cause the parentheses have been solved. This simplifying of equations was to help NOT get this kind of confusion among students. So in reality 6/2(3) is = to 6/2×3... by insisting the parentheses must stay after the inside has been solved and then insisting that you have to do that multiplication is completely bonkers to me. The 2 in front of the parentheses is not part of the set (1+2). There's a whole thing called Set Theory that a guy named Georg Cantor came up with almost 150 years ago that I believe explains this principle.

Bill Eldridge

Just change the rule to PEJMDAS and you can do left-to-right and *still* handle the Juxtaposition in the normally accepted (but not demanded) way (i.e. takes precedence over explicit multiply-divide)

Presumably PEJMDAS is then well-formed and avoids the annoying ambiguity, but i haven't looked for other corner cases.

Dee

The Order of Operations is incorrect for division. That's because 5th grade math teaches that division is a fraction (and vice versa). Also, in teaching how to divide by a monomial in 9th grade Basic Algebra, it is consistently shown as a top-and-bottom fraction. Here are some of the many examples of how these concepts are currently being taught to young math students:

from Teaching Better Lesson.com Common Core:

https://teaching.betterlesson.com/browse/common_core/standard/272/ccss-…

"Interpret a fraction as division of the numerator by the denominator (a/b = a ÷ b)."

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Australian Association of Mathematics Teachers:

https://topdrawer.aamt.edu.au/Fractions/Big-ideas/Fractions-as-division

"Fractions as Division"

"Anyone who has studied secondary school mathematics would probably be comfortable with the convention of 'a over b' meaning 'a divided by b'."

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

from YouTube teaching video:

grade 5:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hfuIUuELmBk

"As you can see a division problem can be rewritten as a fraction. And a fraction can be rewritten as a fraction."

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

from ClubZ Tutoring:

https://clubztutoring.com/ed-resources/math/fraction-bar-definitions-ex…

"FAQ Section

Q1: Can the fraction bar be replaced with the division symbol (/)?

A1: Yes, the fraction bar and the division symbol (/) are interchangeable and convey the same meaning in mathematical notation."

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

from Algebra Class .com: https://www.algebra-class.com/dividing-monomials.html

"Dividing Monomials"

"Remember: A division bar and fraction bar are synonymous!"

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

from OpenStax .com:

https://openstax.org/books/elementary-algebra-2e/pages/6-6-divide-polyn…

Elementary Algebra

"Divide Polynomials"

"Example 6.78

Find the quotient: (18x^3 - 36x^2) ÷ 6x

Solution

Rewrite as a fraction.

18x^3 - 36x^2

-----------------

6x

...Simplify.

3x^2 - 6x "

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

from Slyavula Technology Powered Learning:

https://www.siyavula.com/read/za/mathematics/grade-8/algebraic-expressi…

Grade 8

Algebraic Expressions

"WORKED EXAMPLE 8.2

DIVIDING ALGEBRAIC MONOMIALS

Simplify the following expression:

24t^7 ÷ 4t^5

SOLUTION:

Step 1: Rewrite the division as a fraction

This question is written with a division symbol (÷), but this is the same as writing it as a fraction.

24t^7 ÷ 4t^5 =

24t^7

--------

4t^5

...= 6t^2 "

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

from SlideShare a Scribd Company:

https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/94-16609182/16609182

"Example 3

Divide a polynomial by a monomial

Divide 4x^3 + 8x^2 + 10x by 2x.

4x^3 + 8x^2 + 10x ÷ 2x =

Write as a fraction

4x^3 + 8x^2 + 10x

---------------------- =

2x

Simplify

2x^2 + 4x + 5 "

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

from turito .com math tutoring website:

https://www.turito.com/learn/math/simplify-algebraic-expression

"What are the tips and rules for simplify algebraic expressions?"

"An individual needs to know the rules of simplifying algebraic expressions before solving them. Some basic rules are combined to facilitate the given algebraic expression.

"...Open the brackets in the expression by using the distributive law."

"The distributive property, in particular, asserts that given any absolute values a, b, and c, one should simplify the components of the parenthesis first.

When the elements of brackets are difficult to be simplified, use the distributive property to multiply each term within the parenthesis by the factor outside the parentheses. One can multiply and delete the parenthesis by using the distributive property."

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

from Math Worksheet Center:

https://www.mathworksheetscenter.com/mathworksheets/DivisionPolynomials…

"How to divide a polynomial by a monomial"

"Basic Skills:

"Divide: 16x^5 / 8x^3

A) Divide numbers: 16 / 8 = 2

B) Subtract exponents: x^5 / x^3 = x^2

2 x^2

Answer: 2 x^2 "

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Lumen Learning Courses:

https://courses.lumenlearning.com/uvu-introductoryalgebra/chapter/9-5-d…

"Dividing Polynomials by a Monomial"

EXAMPLE

Find the quotient: 56x^5 ÷ 7x^2

Solution

Rewrite as a fraction

56x^5

-----------

7x^2

...Answer

56x^5 ÷ 7x^2 = 8x^3 "

That can only be true if 56x^5 is the entire numerator & 7x^2 is the entire denominator of the top-and-bottom fraction, even though there are no parentheses anywhere in the original horizontally written division statement using an obelus.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

from BYJUS teaching website: https://byjus.com/dividing-monomials-calculator/

"What is Meant by Dividing Monomials?"

"In Algebra, a polynomial with a single term is known as a monomial. When a monomial is divided by a monomial, first divide the coefficients of the variable and then divide the variable when the variables are present in both the numerator and denominator. For example, assume two monomials, 50 xy and 5y. Now the monomial 50xy is divided by 5y, we will get

= 50xy/5y

= 10x

Thus, the quotient value obtained is 10x, which is the result of the division process."

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

from Cue Math teaching website:

https://www.cuemath.com/algebra/dividing-monomials/

"Practice Questions on Dividing Monomials "

Q.1. Divide. 15a^2b^3 ÷ 5b "

Correct answer is shown as 3a^2b^2.

That can only be true if 15a^2b^3 is the entire numerator & 5b is the entire denominator of the top-and-bottom fraction, even though there are no parentheses anywhere in the original horizontally written division statement using an obelus.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

from GeeksforGeeks .org

https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/how-to-divide-monomials/#

"A monomial is a form of a polynomial with a single non-zero term. Because a monomial has only a single term, it is simple to do addition, subtraction, and multiplication. It is composed of only one variable, one coefficient, or the product of a variable and a coefficient, with exponents as whole numbers representing only one term."

"...when dividing monomials, divide the coefficients first, then divide the variables. When there are exponents with the same base, divide by subtracting the exponents according to exponent rules.

Example: 16mn ÷ 4n

= (16/4) (m) (n/n)

= 4mn "

* * * * * * *

In light of how division of monomials is currently being taught, given that x does not equal zero, what is the quotient of 2x divided by 2x, whether written as 2x ÷ 2x or written as 2x/2x or written as the top-and-bottom fraction...

2x

---- = ?

2x

Pumpkin1

For the life of me, I do not understand what happened to the distributive method of resolving parentheses. While I find the article at the top of this page to be very informative, and it does mention the distributive method, it fails to answer why so many people seem to have forgotten about it! I have had multiple people tell me it is only used when you have variables. This makes no sense as the equation comes out differently with variables versus constants. Whether it has constants or variables, the parentheses need to be expanded first, and this is only done with one method: (2*2)+(2*1)=6, then you can divide this resultant into 6.

Doug

Refreshing point. That is why old text books would evaluate the items on either side of the divide ahead of the divide - i'll be they were protecting the principle. I think I recall so, but it has been many decades but I think the principles were introduced just ahead of these kinds of examples. One of the videos on this says this was an out of vogue view. You make a great point

that it cannot be out of vogue, its essential.

Carlos R Irizarry

6/(3)2= 4

Now I am really confused !!!

Clayton

Like the other guy said, multiplication is commutative, however, in the problem the 2 is actually 1/2 due to the ./. [fraction] sign

so it's 6*(1/2)(2+1)

It's really about what operation is being performed here, then perform the correct order. 2(2+1) has the multiplication operation being used. The problem is [logically] solved as 9 using this simplicity.

Dee

Below is a link to a teaching website that allows a person to ask an AI tutor a math question:

https://www.ck12.org/flexi/cbse-math/divide-fractions/how-do-you-turn-a….

I asked:

In Algebra, how is one monomial divided by another monomial written, using a slash?

The answer given by the AI tutor was:

When one monomial is divided by another monomial, it is written with a slash (/) between the two monomials. For example, if you have the monomials a and b and the division would be written as a/b.

The AI system then asked me:

Would you like to try a question based on the concept above?

I answered "Yes."

Here is what the system replied:

If a monomial is written as 8x^2 and another as 4x, how would you write the division of the first monomial by the second using a slash?

I replied:

8x^2/4x

The AI tutor responded:

Partially correct

You're on the right track! When dividing monomials, you write the division as a fraction or with a slash. So, 8x^2 divided by 4x is indeed written as 8x^2/4x.

However, it's always a good idea to simplify when possible. In this case, 8x^2/4x simplifies to 2x.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The only way to obtain the quotient of 2x from the monomial division expression of 8x^2/4x is if the AI tutor on this math teaching website treated it as the top-and-bottom fraction of...

8x^2

------

4x

With that being the case, 2x divided by 2x is 2x/2x, which can also be written as the top-and-bottom fraction...

2x

---

2x

...which equals 1.

6/2(1+2) is the exact same monomial division as 2x divided by 2x when x=3 or x=(1+2), regardless of whether the division symbol is an obelus, a slash or a fraction bar (since all division symbols mean "divided by" & separate the dividend/numerator from the divisor/denominator). Ultimately, it's 6 divided by 6, which equals 1.

Anonymous

Hi David. I'm sure you reached a satisfactory conclusion and certainly don't intend to discuss this particular topic any further, but use it to move on. I do hope you read this as I note your research is in set theory and the title of your article here includes the word "paradox".

There's also a famous paradox in set theory known as the Russell paradox (and its equally famous "barber" version) and it's my contention that this too is really an order of operations of operations problem just like the one here, and could just as easily be resolved with brackets, conventions like PEMDAS, or some other order marker.

In fact this paradox has little to do specifically with sets at all. It works for just about any other subject-verb- object formation, for example: man-shave-man, set-belong to-set, dog-eat-dog, including those occasions when that object is the reflexive pronoun him-/her-/itself. I suggest that the confusion arises not with the nature of the grammatical subject but with the tense of that verb. It arises from failure to recognise that each successive appearance of the verb in the argument that sets out the paradox is logically, if not grammatically, a different tense and refers to a different time. The paradox disappears when we make that difference explicit, when we differentiate with respect to logical time. The barber shaves today all and only those people who didn't shave themselves yesterday, so if he didn't shave himself yesterday, he does today. The Russell set includes all and only those sets which didn't previously include themselves. So if it didn't include itself before it does now, but if it did before then it doesn't now.

In math when faced with the contradictory result arising from failure to put explicitly different relative times on the division, multiplication, and addition operations in an expression like 6 ÷ 2(1 + 2) = 4 we eventually find a way of nailing them down, so too with the operations of set inclusion and exclusion, or shaving and not shaving, or whatever.

Geo Nalugala

There is a solid reason why some math problems take centuries to resolve: it is because simplistic people run away from the challenge.

***

Take a simple example: the area of a right triangle = ½bh or ½*b*h. Suppose it has basic side lengths 3, 4 & 5.

Irrespective of which is the base or height,

Area = ½*3*4 = 6.

So, given the Area (6) and one side (base), what is the other length (height)?

Area ÷ ½ * b = h.

Area ÷ ½ * h = b.

I am arguing that ½*b is one term, even without parentheses.

So that:

6 ÷ ½ * 3 = 4.

6 ÷ ½ * 4 = 3.

Professors, even from Harvard and Cambridge (UK) want to insist here that division "ranks equally with multiplication." It does not!

So, their 6 ÷ ½ * 3 = 36.

And their 6 ÷ ½ * 4 = 48.

"BECAUSE Google and WolframAlpha also said so!"

Men and women of the world, that is completely stupid. You know the area of a right triangle is settled math.

Why do you ignore your own brain, and trust robots? Computers are not perfect. They are less than 70 years old in combined developmental age. The human brain has at least 200 million years of arithmetic progress. Within this timeline, it has made these confused computers. Trust your head more.

Ignacio Calvo

The problem is that, given the final expression 6 ÷ ½ * 3 we don't really know where it came from. OF COURSE if we know is the result of calculating the area of a triangle we could maybe infer that ½ * 3 is half the length of a side or a height and then the only sensible thing to do is group that. But triangle areas are not the only subject we could arrive this expression from.

For example, let's take another super-basic mathematical calculation, the cross-multiplication, where you know that a couple of ratios are equal: a ÷ b = c ÷ d, and you must calculate one of the topmost variables, either a or c (direct cross-multiplication). For example:

a ÷ b * d = c

c ÷ d * b = a

Now we should conclude that a ÷ b and c ÷ d are one term, even without parentheses, right?

So that:

1 ÷ 2 * 6 = 3.

3 ÷ 6 * 2 = 1.

And therefore we would consider these other calculations (that use your logic of grouping the multiplication) nonsensical:

1 ÷ 2 * 6 = 1 ÷ 12.

3 ÷ 6 * 2 = 3 ÷ 12 = 1 ÷ 6.

Jim

a/b = c/d

(a/b)d = c

(1/2)6 = 3

(c/d)b = a

(3/6)2 = 1

John Smith

1 (meaning that juxtaposition has higher precedence) is what makes sense

it makes life easier and it is more intuitive

people only say 9 because they are using the oversimplification they learned at kindergarten

Piotr Grochowski

Math syntax is only a syntax error when there are undefined symbols, or when the expression has no numbers in it. So 6÷2(1+2)=9 with no syntax error.

(3×(3)+3)=12

(3+(3)×3)=12

[3×(3]+3)=18

[3+(3]×3)=12

(3×[3)+3]=12

(3+[3)×3]=18

[3×[3]+3]=12

[3+[3]×3]=12

Also, parentheses have precedence over brackets.

Doug

Who's syntax check? Here's an interesting case where

=6/2(1+2)

is a syntax error:

LibreOffice Calc found an error in the formula entered.

Do you want to accept the correction proposed below?

=6/2*(1+2)

Accepting the proposal yields 9. But it refused to assume that was the intended meaning.

This is a great choice because otherwise you would have to have a setting as to

which convention would be used to resolve the ambiguity of whether the 2( was distributed or

just multiplied. It is perhaps interesting to note that did not offer=6/(2*(1+2)) instead

suggesting simply multiply might be the usual meaning.

mtd

Late to this post but it's a pretty good article so I wanted to discuss it further.

Isn't there a further contradiction with the whole a(b) = (ab) argument in the choice of a?

If you have 6/2(1+2), then what determines that a = 2 and not 6/2?

Seelang2

I was going to comment this exact thing. Calling this an issue with an acronym for order of operations and suggesting a paradox doesn't really make sense when the real reason for the ambiguity of the expression is because of dissension on whether the term a in a(b) in this case is 2 or 6/2.

If this had been written using a vinculum instead of a solidus (or worse, the obelus) the ambiguity would be resolved:

6

-- (1 + 2) = 9

2

versus

6

--------- = 1

2(1 + 2)

Saying that there is no recognized standard also doesn't seem accurate. What about ISO 80000-1 and ISO 80000-2? ISO 80000-1:2009 section 7.1.3 which discusses printing rules for mathematical expressions indicates:

a

--- = a / (bc), NOT a/b · c

bc

ISO 80000-2:2009(E) also states that only the vinculum and solidus are acceptable as general division operators. A colon should only be used for ratios and the obelus should. not be used at all.

There's also the Physical Review Style and Notation Guide by the American Physical Society, but if I were to choose a standard, I'd go with an internationally recognized standard.

My question is, since there are in fact published international standards regarding presenting mathematical expressions (and in part their interpretation as noted above), why isn't the academic community either aware of or using those standards when teaching, particularly in getting rid of using the obelus altogether?

Pumpkin1

We are in agreement with the answer of 1, but I will take it one step further. Regardless what indicator is used to show division, the equation is still clear. I know of only one method to resolve parentheses and that is with the distributive method. Regardless how the equation is written, you will always end up with (2*2)+(2*1)=6.

douglas fowler

What is 8/2*4

Jim

"If you have 6/2(1+2), then what determines that a = 2 and not 6/2?"

If a = 6/2 then the expression would be presented as (6/2)(1+2).

Is it not usual when a constant or variable is defined as a term or expression of numbers that the numbers be enclosed in parentheses?

Fabripol

if a=(1+2) what does PEMDAS say?

You see (6/2)a or 6/(2a)?

Dee

A monomial is one term with a single value which is the PRODUCT of the coefficient multiplied by the variable (factor). It uses multiplication by juxtaposition to "glue together" the coefficient & the variable (factor), so no parentheses are ever necessary to understand that a monomial is one term with a single value.

In the case of the monomial "2x ," that means "x" is taken two times, which means the term's value is the sum of two x's added together. In other words...

2x = [ x + x ]

Here's a statement which is dividing one monomial by another monomial:

2x ÷ 2x

...which can be written out with the indicated additions as...

[ x + x ] ÷ [ x + x ]

Solve when

x = (1+2)

Please show the steps involved in solving.

Lucky13pierre

Using a real life problem to reach the solution, imagine you have 6 sweets and 2 groups of 1 girl and 2 boys to share them around.

The kids all get one sweet each, so the answer is 1. If the answer were 9, you'd be creating 3o sweets out of thin air!

Don MacQueen

Using a real life problem to reach the solution, imagine you have 6 index cards and one group of 1 girl and 2 boys. Your instructions are to first get rid of half of the cards, then give one card to each child, then tell each child to tear their card into 3 pieces.

You now have 9 pieces, so the answer is 9.

And who is to say which "real life problem" is the correct one? Nobody. We can always invent a word problem to fit whatever arithmetic steps we want.

(and, yes, it's been 8 months, so probably nobody will ever read what I wrote...)

Pumpkin1

David, in your exceptional article, you mentioned that the people in the 1 category will sometimes point to the distributive method for how to get an answer of 1. If the distributive method is not used in this type of equation, where is it used? Be gentle with me! I am an engineer, not a mathematician!

Andy

I do wish the international body of mathematicians could sort this one out. In algebra the implicit multiplier is always understood to take precedence. In other 'random' mathematical expressions whoever gave the mathematical world the permission to arbitrarily express 2*(1+2) as 2(1+2)? In order to follow logical consistency we spend years teaching kids algebraic mathematics where 2X is always 2X (inseparable and implicit takes precedence). If you wish to express 6 / 2 * (1+2) you simply do not have any permission to lazily and arbitrarily express it as 6 / 2(1+2) for this very reason. I know that even the maths professors are contorting themselves over this, but I think it should be sorted out. And logically it should simply be nailed down that implicit multiplication takes precedence because otherwise all of algebra is wrong. ab no longer means ab. I thought it was. I was taught Brackets Of Division (2 of something takes precedence over division and multiplication). But it turns out even that is not agreed on as more seem to hold to BODMAS meaning 'Brackets Orders Division...'

Don MacQueen

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has a document ISO 80000-2 whose topic is "Mathematical signs and symbols to be used in the natural sciences and technology".

It says (in a 2020 version), regarding the two standard symbols for multiplication, "Either symbol may be omitted if no misunderstanding is possible". It does not follow up by saying that when the symbol has been omitted the multiplication automatically rises to a higher level of precedence.

Consider four expressions:

4+(5-2)

4-(5-2)

4*(5-2)

4/(5-2)

The notational convention is that in one of those four cases the operator adjacent to the opening bracket can be omitted. That case is multiplication.

The idea that omitting the operator automatically gives it higher precedence than division is ludicrous. Omitting the operator can not, and should not, change its meaning.

Of course, it is true that algebraic notations such as xy or 2x are considered grouped. But the similarity of, for example 2(3), to such algebraic expressions superficial, and is not a basis for considering 2(3) grouped.

That's my perspective, anyway.

Dee

What is a monomial?

Permalink Submitted by Dee (not verified) on 25 March, 2024In reply to "Implicit" multiplication by Don MacQueen (not verified)

Think back to 9th grade Basic Algebra class, when your teacher covered what a "term" is (specifically a monomial) & how to divide one monomial by another monomial.

The term "4x" is a monomial because it is a coefficient and a variable. Given that "x" does not equal zero, the monomial "4x" holds a single value, which is the coefficient of "4" multiplied by whatever "x" equals.

An example of the value of the value of a monomial would be if I said I had bought 4 dozen eggs, you would understand that " 4 dozen" is a single total quantity of eggs-- 4 cartons of a dozen eggs each equals a total quantity of 48 eggs. In other words...

4 dozen = 1 dozen + 1 dozen + 1 dozen + 1 dozen

In your local diner, if 4 dozen eggs were to be split evenly amongst 2 groups of a dozen people each, how many eggs would each customer get?

4 dozen eggs divided by 2 dozen customers

4 dozen ÷ 2 dozen

4(12) ÷ 2(12)

48 ÷ 24 = 2

Now replace "(12)" with the variable "x." The statement is now:

4x ÷ 2x or 4x / 2x

...which is also correctly written as 4x over 2x.

The like variable of "x" cancels out, leaving 4/2 or 4 over 2, which equals 2.

The calculation represents that each diner customer gets 2 eggs, no matter which division symbol is used (obelus, solidus, or vinculum) and/or if the word "dozen" is used (and if x = dozen)

Your 9th grade Basic Algebra teacher explained that a monomial never needs parentheses because it is ONE TERM with a SINGLE VALUE which is the PRODUCT of the coefficient multiplied by the variable. The coefficient cannot be "peeled off" & used in some other operation in a horizontally written division statement. A monomial does not need to be encase inside of parentheses any more than the term"4 dozen" needs parentheses around it to be understood as a total quantity of 48 -- it's the same implied multiplication by juxtaposition as "4x," which is a monomial.

vinixec

This is a complete use or words but not use simple Arithmethic for resolve.

1. Arithmetic try to solve many terms into 1.

2. When we dont see any agrupation signal we know there's an order to solve any problem.

3. Calculators can't make maths, just only results.

4. Your single example corrspond to the form c:b(a+b). Simple algebraic definition. ¿Where is the rule that show me Wolframs is superior to math for follow your suggested formula?

5.This nosense publication correspond to try to insert deconstructional Gramsci thinking where it is impossible to do. And follow same steps in the science of maths, bases starts in arithmethics.

2 Results:

2.1. Arithmetican: 1

Lol