Time and the multiverse

This article first appeared on the FQXi community website, which does for physics and cosmology what Plus does for maths: provide the public with a deeper understanding of known and future discoveries in these areas, and their potential implications for our worldview. FQXi are our partners in our Science fiction, science fact project, which asked you to nominate questions from the frontiers of physics you'd like to have answered. This article addresses the question "What is time?". Click here to see other articles on the topic.

For many of us, this song from Casablanca evokes memories of romance. But to Laura Mersini-Houghton it may provoke deeper questions about the foundations of reality: why can we only remember the past, not the future? And what is the origin of the arrow of time? Her conclusion is that time's arrow is not as fundamental as we may believe.

Mersini-Houghton's view of time comes from looking at the bigger picture — the biggest possible picture, in fact. With the help of a $50,000 grant from FQXi, she is investigating the possibility that our universe is just one of many in a multiverse of universes and what that means for time's arrow.

Womb to tomb

We travel through life from womb to tomb, not vice-versa, yet physicists have no real explanation for why time flows in only one direction. The microscopic laws that underlie the behavior of particles have no such arrow, working equally well backwards as forwards. So why doesn't time run backwards?

Laura Mersini-Houghton.

Physicists usually explain the arrow of time using the concept of increasing entropy — a measure of the disorder of a system. The universe evolves from a highly-ordered, low-entropy beginning, to a progressively more disordered state, defining time's arrow. So, sugar cubes dropped into coffee dissolve as time passes, increasing the disorder of the coffee-sugar system; but they do not re-solidify. To Mersini-Houghton, a physicist at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, however, this reasoning simply begs the following question: why did the universe begin in a highly unlikely low-entropy state in the first place?

The multiverse view offers a simple answer: if there are an infinite number of cosmoses, it would make sense that at least some universes should start in a low entropy state. Mersini-Houghton first became interested in the idea of a multiverse with the advent of the string-theory landscape. In 2003, string theorists began to realise that their equations offered a staggering 10500 equally-valid solutions, each of which could describe a possible universe. Suddenly there was talk of a string landscape — a multiverse of universes, each with different physical laws.

This landscape provides the basis of Mersini-Houghton's model. Each new universe forms in this landscape as a bubble, with some intrinsic vacuum energy — similar in character to the dark energy causing today's universe to expand at an ever-increasing rate — that drives it to inflate. At the same time, matter causes the bubble to try to crunch back down. "It is this tug-of-war that determines whether a universe can be born or not," says Mersini-Houghton.

Crucially, in this model, only high-energy bubbles will overcome the matter crunch and grow into full-blown universes. These bubbles would have started out with low entropy, explaining the seemingly unlikely initial conditions of our universe.

Arrowless time?

Mersini-Houghton claims that time in the larger multiverse is arrowless, favoring no particular direction. But while the physical laws in each baby universe inherit this time-symmetry, the bubbles themselves do not. That's because at the moment of its birth, the bubble loses information about the multiverse. This information loss results in growing disorder, says Mersini-Houghton. In other words, entropy starts to increase in the bubble, creating a local arrow of time.

To describe the dynamical evolution of the bubble, Mersini-Houghton uses a quantum-mechanical master equation. "It's important to derive everything from an existing, fundamental theory," she explains. But this comes at a price: since there is currently no working theory that unites quantum mechanics with general relativity, Mersini-Houghton assumes that the laws of quantum mechanics are more fundamental than those of general relativity.

However, not all cosmologists think the role of general relativity can be downplayed. FQXi essay contest winner Sean Carroll at Caltech, in Pasadena, is also independently tackling the issue of time in the multiverse but, by contrast, he is using a semiclassical quantum-gravity approach. His model also contains a parent multiverse, with no overall arrow of time.

"You start with a spacetime that has no directionality of time, which makes sense given that the underlying physical laws are like that," says Carroll. In his model, baby universes preferentially begin with low entropy. Once grown, each universe can eventually give birth to new universes, which arise due to quantum fluctuations in the presence of vacuum energy. These universes have arrows of time pointing in different directions, so, in some universes, time could actually run backwards.

Time flowing backwards is less mind-boggling than it sounds, says Carroll reassuringly. In what we call the past there are universes where, from our point of view, entropy is increasing towards the past. But in the same way, from their point of view, entropy is increasing towards the future and we're in their past. "Everything is completely symmetric," he says. "Backwards is in the eye of the beholder."

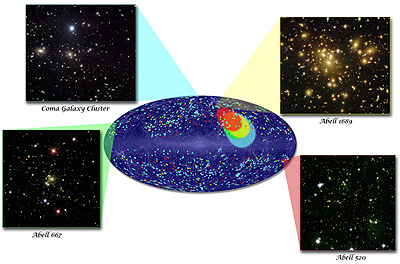

The pull of the multiverse? The coloured dots in the image mark clusters at various distance ranges. (Redder colors indicate greater distance.) The coloured ellipses show the direction in which clusters of the corresponding colour are being pulled. Images of representative galaxy clusters in each distance slice are also shown. Credit: NASA/Goddard/A. Kashlinsky, et al.

This all sounds nice in theory. But given that we are locked within our universe, can we possibly ever test whether a multiverse exists, let alone whether it has an arrow of time?

Mersini-Houghton thinks so. In her model, baby universes retain a vague, gravitational influence on each other even after they lose information about the multiverse. In 2006, she predicted that this ghostly cross-talk would result in a peculiar "pull" on galaxy clusters in one part of the sky. Last year, such an effect, dubbed dark flow, was surprisingly observed by NASA. There is no consensus as to what causes the flow, but Mersini-Houghton is excited: "I never thought we'd see anything like this, at least not in my life time."

Mersini-Houghton had also predicted that a neighbouring universe could create a giant void in space by pushing against us, repelling gravity and matter. A few months later, the discovery of such a void using radio telescopes at the Very Long Baseline Array in New Mexico was reported. But this result was called into question in 2009, when astrophysicists at the University of Michigan claimed that the evidence for the void was a statistical blip.

Despite this setback, Rüdiger Vaas, a philosopher of science from the University of Stuttgart, says that one of the main advantages of Mersini-Houghton's model is that it is testable. "You can derive predictions and it is possible to test them right now," he says. "Although it's currently not clear whether it's true or false, it looks very promising."

So will Mersini-Houghton’s latest predictions ultimately stand up to scrutiny? Only time will tell...

About this article

This article first appeared on the FQXi community website, which does for physics and cosmology what Plus does for maths: provide the public with a deeper understanding of known and future discoveries in these areas, and their potential implications for our worldview. FQXi are our partners in our Science fiction, science fact project, which asked you to nominate questions from the frontiers of physics you'd like to have answered. This article addresses the question "What is time?". Click here to see other articles on the topic.

Comments

Anonymous

"Physicists usually explain the arrow of time using the concept of increasing entropy (...) The universe evolves from a highly-ordered, low-entropy beginning, to a progressively more disordered state, defining time's arrow."

I'm not sure, but for me it looks like circular reasoning.

First there is assumption, that there are previous and next states (this implies directionality), and next states are more disordered than previous states, thus entropy is increasing.

Then there is explanation, that time (directionality) exists, because entropy is increasing.

So directionality exist, because there is directionality?

Please correct me, if I'm wrong.

Arek W.

Anonymous

Newtonian mechanics shows that the entropy of a closed system increases or remains the same. No heat engine can operate at 100% efficiency but statistical thermodynmaics does not necessarily show that you MUST increase in entropy all times. It is a probabilistic statement. There is a probability that when you turn on the flame under a pot of water that the water will turn to ice. Sure, the chances are small, but there is a finite probability.

Time is not positive or negative in the equations for relativity and you will have the same results for positive time and negative time. Time, therefor has no direction. Direction exists in our minds only - multi-verse-iality just shows this. Now, with the idea of the multiverse existing in this state - time Would indeed have direction.....

R denis

Anonymous

Yes, I understand, that entropy is probabilistic and could increase locally through pure chance (but averagely in the whole universe it's decreasing). I also understand, that it's us, who ascribe (one) direction to time.

What I am concerned with, is definition (it's not official definition I think - it's rather how to describe time using entropy). It seems circular to me. I tried to think about it more, but it didn't help. I'm pretty sure that I'm missing something, but I don't know what is it.

Arek W.

Anonymous

I think the issue is that the arrow of time, the perceived direction of time, IS the increasing of entropy. We observe changes in state, seemingly always in the direction of increased disorder of the system, and we refer to this experience as "the arrow of time". I think time, fundamentally, is very much the twin of space in the multiverse as a whole, where any potential agent could traverse it in a non-linear fashion, but once a universe is closed off, time loses this quality(as it is cut off from meta-time, if I can call it that) and what we experience as time is only the system changing state from ordered to disordered to final total dispersion of matter/energy. As the article stated, no matter what way the arrow "points" it's just always going from ordered state to disordered, so the terms, imo, are really synonymous or a tautology, an arrow of time IS the overall increasing of disorder, as perceived by a conscious agent(us). I don't see it as circular because we experience a flow of time and observe this "flow" only in terms of change and only in the direction of increased entropy, forming our arrow of time, which is just a description of particularly difficult concept to articulate. Personally, I think this hypothesis is the most compelling of the multi-versal ideas of time. Sorry if I misunderstood you and totally missed your point, but that's my take on it. =)

Anonymous

Are we truly alone? We may never know...

Anonymous

I may not be as versed in this particular topic as others, but I gather the general theory is equal to saying if at some point (in a unidirectional form of time that is), we had several singularities or regions in space. If at different points, some singularity or something erupted to have all sorts of particles to come about, we have matter, and several "universes" creating more disorder. As a result, we had more entropy as more events came to be.

What if something resembling a multi-verse came into being after the beloved "big bang" theory? Assume if we had some singularity that came into being through something we don't know of, can't perceive or realistically quantify other than in hypothesis or theory. From there, we suddenly have some emission of particles. What if we had something emit from that singularity in a very random or non uniform way?

If that were the case, and how particles attract and repel each other, we would have a lot of entropy increasing. If that was the case, what if these other "universes" simply came from something like that?

If we perceived things like that, pending on ones frame of reference, we know that we would have certain places where there is a stronger force of gravity, and based on Einstein's theories, gravity curves space-time, and space-time can impact gravity. So in that aspect, and pending on your definition as to what a "universe" is, and pending on how you define space time in mathematical terms, there could be some validity to the theory or at least a perspective from certain conditions and a frame of reference where this could hold true. Yes?

Assume we had some singularity called s sub 0. From there, we have others emit from it in some way, and s sub 0 contains other smaller singularities of particles. These things suddenly for whatever reason(s) disperse in some non uniform means. Suddenly we have s sub 1 through n, and n approaches infinity perhaps.

Within the confines of 3 space, each s sub m (m being an element of real non zero integers) lives somewhere in outer space. Each s sub m is a smaller singularity of what once was s sub 0. Maybe from there as these things happen, we have some other particles release, and interact with whatever and are acted upon by some other singularity s sub m. Each s becomes it's own universe. From there, it acts as it's parent did, and whatever particles are out there, and as entropy increases, things evolve.

If each s has it's own gravitational force, it can tell space time how to behave in a given direction pending on how you define space time to be in mathematical terms. Therefore, it could be multi-directional, but time as we perceive it to be on earth is one thing. We would have to describe time behaving differently for each "universe", and time being relative to time in another "universe" to create a multiverse in the context of this theory. Yes?

In short, I suspect that some form of chaos had to have came about from the inception of the universe from however it came to be or something random. If everything was nice and orderly, and things burst from a given singularity, and things evolved in a very nice and predictable manner, we'd have an empty bubble filled with particles. However, if we had a certain distribution of particles as we know them to be in this day and age, or something else more random, that could explain some things. However, if there was a multiverse, how did that come into being?

I think there had to be some disorder from the inception of all that is for things to be as they are. (shrugs)

Joe in Monroe, NC

Andrew7k9

my question is, is this multiverse eternal or does it have a beginning or some sort of cause