Outer space: Archimedean ice cream cones

There are many situations in the natural world where having lots of surface area is advantageous and natural selection will reward you for it. We think of the branchiness and leafiness of trees which have developed fractal structures to maximise the area of their light and nutrient gathering surfaces compared to their weight or volume. This is one of the reasons why natural curves and shapes are frequently jagged while humanly engineered one, like aerofoils and car bodies, are smooth — they are optimising something else.

What are the optimal dimensions?

Hence we see that we need $$V=2\pi r^{3}$$ and so, since $V=h\pi r^2$, we need $h=2r$ for the most economical tin can: its height equals its diameter. You might like to check that if you were making a cylindrical mug — so there is no top — then the best proportion is flatter, with $h=r$. If you look around the supermarket shelves you will find some cans that have the optimal diameter equals height shape but many do not. Perhaps they just want to look different and stand out on the shelves? Incidentally, if we had changed our problem to find the shape that maximised the volume enclosed by a given area, can you guess what the answer would be?

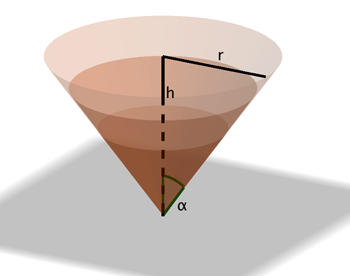

Now as in our problem of the tin can, we substitute for $h=3V/\pi r^{2}$ in the formula for $A,$ calculate $dA/dr$, and set it equal to zero. We have $$dA/dr=\pi \left[ r^{2}+\frac{9V^{2}}{\pi ^{2}r^{4}}\right] ^{1/2}+\frac{\pi r }{2}\left[ r^{2}+\frac{9V^{2}}{\pi ^{2}r^{4}}\right] ^{-1/2}\left[ 2r-\frac{ 36V^{2}}{\pi ^{2}r^{5}}\right].$$ Setting this equal to zero, the result is $$r^{3}=3V/\pi \sqrt{2}=r^{2}h/\sqrt{2}$$ and so the optimal height to radius ratio for the best ice cream cone is $ h/r=\sqrt{2}.$ Therefore, since $r/h=1/\sqrt{2}$ is the tangent of the angle $\alpha$ that the vertical through the point of the cone makes with the side, this angle is $\tan^{-1}{(1/\sqrt{2})} = 0.6$, measured in radians. This corresponds to $35.26^{\circ }$ or $35^{\circ }15^{\prime }$. In some sense this is the most economical cone.

The differently shaded regions in the image above indicate three cones of different volumes, but each with a value of $\alpha$ that guarantees the minimal surface area for its volume. The Geogebra applet below shows all the cones of a given volume (which we have arbitrarily chosen to be 6). You can use the slider on the top left to change the radius of the cone, which also changes its height accordingly. To keep the volume constant, the point A needs to lie on the black curve. When A=D the surface area of the cone is at its minimum. As we have calculated, this happens when the angle at the apex of the cone, between the vertical and a side, is approximately 35 degrees.

Comments

Mark McCartney

There is a nice letter from the Carnation canning company which is reproduced in Applied Mathematics by Farlow & Hagggard (Pub. Random House, 1988) p613 on why cans do not adopt this optimal shape.

mathwizard

"If you look around the supermarket shelves you will find some cans that have the optimal diameter equals height shape but many do not. Perhaps they just want to look different and stand out on the shelves?"

Well, not really, the real world is more complicated than this. You have to consider manufacturing process: the ends of the cylinders (the two circles) most likely have to be cut from planar material. So one has to consider minimizing wastage as well. We of course know that arranging the circles in a hexagonal array would do the job (this is the "optimal packing"), so it works out that the area to be minimized is really A=4*sqrt(3)*r^2+2V/r. This model would predict that can should be 10% higher than its wide. But in reality we observe differences -- this is true for small cans, like a can of drink. But huge can like a can of paint does tend to have h=2r. A better but more complicated model, taking into account the wielding cost, could explain why its more economical to have huge can be more "squarish", but small can to be tall and thin.

Beebeeoii

Is this still possible for objects with an irregular shape? Because for those objects, there's no defined equation that links its surface area and volume with its radius. For example, a Pepsi bottle. The only way to find the exact volume is via integration. But how about the surface area and after that how to do dA/dr?

All help appreciated. Thanks!

daCake

Please note that the formula for the surface area can be rewritten as A = pi \times \sqrt{r^2 \times ( r^2 + h^2 )} (LaTeX notation). To maximise A it suffices to maximise the radicand. Since it's quite easy to substitute r^2 by using the equation for the cone volume V, we have a function of h rather than a function of r. It's derivative can be calculated essentially by using the product, quotient and addition rules for derivatives. The numerator of the derivative is given by 3V \times ( h^3 \pi - 6V ). From this we have a zero derivative if h^3 \pi = 6V. Again use the equation for the cone volume to find that h^2 = 2 r^2 or h/r = \sqrt{2}.

Anthony Hughes

The only way to find the exact volume is not by integration, but by filling the object (i.e. pepsi bottle) with water and pouring it out into a measuring cylinder. This is similar to the problem, allegedly given by Thomas Edison to a young mathematician, to find out the exact volume of his new invention, the light bulb. After spending days finding a function to represent the curved surface of the bulb and then integrating it to calculate the volume he told Edison the answer. Edison then inverted the bulb and filled it with water and then measured the volume of the water, and replied "Yep, that seems about right." Now that's how an engineer would approach it.