Outer space: Superficiality

Boundaries are important. And not only because they keep the wolves out and the sheep in. They determine how much interaction there can be between one thing and another and how much exposure something local might have to the outside world.

A wiggly line is longer than a circular one.

Take a closed loop of string of length p and lay it flat on the table. How much area can it enclose? If you change its shape, you notice that by making the string loop longer and narrower you can make the enclosed area smaller and smaller. The largest enclosed area occurs when the string is circular. In that case we know that p = 2πr is its perimeter and A = 4πr2 is its area, where r is the radius of the circle of string. So, eliminating r, for any closed loop with a perimeter p, which encloses an area A, we expect that p2≥πA, with the equality arising only for the case of a circle. Turning things around, this tells us that for a given enclosed area we can make its perimeter as long as we like. The way to do it is to make it increasingly wiggly.

Fish gather in a near-spherical shape to protect themselves against predators. Image courtesy Global Vision International.

If we move up from lines enclosing areas to surfaces enclosing volumes, then we face a similar problem. What shape can maximise the volume contained inside a given surface area? Again, the biggest enclosed space is the sphere, with a volume V = 4πr3/3 enclosed by a surface of area A = 4πr.2 So for any closed surface of area A we expect its enclosed volume to obey A3≥36πV2, with equality for the case of the sphere. As before, we see that by making the surface highly crenellated and wiggly, we can make the area enclosing a given volume larger and larger. This is a winning strategy that living systems have adapted to exploit.

There are many situations where large surface area is important. If you want to keep cool, for example if you are an African elephant, then the larger your surface area the better (conversely if you want to keep warm, it is best to make it small — this is why groups of new born birds and animals huddle together into a ball). But if you are a flame, you can't be too small.

A model of a set of lungs. The intricate branching guarantees maximal exposure to oxygen molecules. Image courtesy Professor Ewald R Weibel, Institute of Anatomy, University of Berne.

If you are a tree that draws moisture and nutrients from the air, then you want to maximise your surface area interfacing with the atmosphere, so it's good to be branchy with lots of wiggly leafy surfaces. If you are an animal seeking to absorb as much oxygen as possible through your lungs, then this is most effectively done by maximising the amount of tubing that can be fitted into the lung's volume so as to maximise its surface interface with oxygen molecules. And if you simply want to dry yourself after getting out of the shower, then a towel that has lots of surface is best. So towels tend to be knotted and irregular on their surfaces: they possess much more surface per unit of volume than if they were smooth.

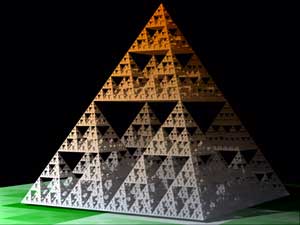

The Sierpinski Pyramid.

This battle to maximise surface enclosing volumes is something we see all over the natural world. It is the reason that fractals so often appear as an evolutionary solution to life's problems. They are the simplest way to systematically increase the surface area surrounding a volume. Fractals like Koch's Snowflake and Sierpinski's Pyramid allow us to construct curves which enclose a finite area but have an infinite length, and surfaces which enclose a finite volume by an infinite area. In reality, these infinities can never be realised because of the intervention of physical forces, which prevent further smaller wiggles being made. But natural systems make repeated use of the same general strategy when they want to be as superficial as possible.