Circles rolling on circles

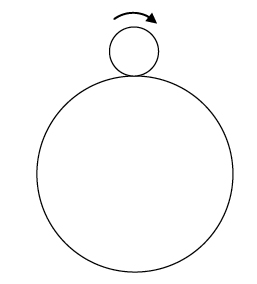

How many revolutions will the smaller coin make when rolling around the bigger one?

Imagine a circle with radius 1 cm rolling completely along the circumference of a circle with radius 4 cm. How many rotations did the smaller circle make?

The circumference of a circle with radius  is

is  , so the circumference of a circle with radius

, so the circumference of a circle with radius  would be

would be  . Since

. Since

I figured the answer must be four revolutions. So imagine my surprise when I saw that the answer was given to be five!

I read the explanation of why this was indeed the correct answer, and although the reasoning seemed sound, it took some time before I could truly convince myself that my solution was in error. It’s an interesting problem, so I presented it to a number of people, most of whom immediately answered "four" as I did, and, like me, were difficult to convince otherwise; only a very few could intuitively see "five" as the correct answer.

Here’s a better way to think of this problem: rather than rolling along the larger circle, start by imagining the smaller circle as rolling on a line the same length as the circumference of the larger circle. In this case it is straightforward to think of the line as being  units long, and so the smaller circle clearly must have made

units long, and so the smaller circle clearly must have made  rotations. Next, think of the circle as sliding along the line, without rolling, so that the point on the coin at which it touches the line remains the same. Now consider the difference between sliding along a straight line and doing the same along the circumference of a circle; if you slide units

rotations. Next, think of the circle as sliding along the line, without rolling, so that the point on the coin at which it touches the line remains the same. Now consider the difference between sliding along a straight line and doing the same along the circumference of a circle; if you slide units  along a straight line, you arrive at your destination just as you started, without having ever changed orientation. But if you do the same along the circumference of a circle you will have made a full rotation at the time you return to your starting point. When rolling along the same circumference, therefore, you will have made the four rolling rotations plus the one sliding revolution, for a total of five!

along a straight line, you arrive at your destination just as you started, without having ever changed orientation. But if you do the same along the circumference of a circle you will have made a full rotation at the time you return to your starting point. When rolling along the same circumference, therefore, you will have made the four rolling rotations plus the one sliding revolution, for a total of five!

Put differently: when the small circle rolls along the circumference of the larger circle, two kinds of movement simultaneously occur, revolution and rotation. The four movements one initially considers are the four revolutions, perhaps because these are readily seen. Rotation, on the other hand, is more difficult to grasp.

It’s difficult to make progress on this kind of problem just by thinking about it, so it is important to verify the situation through experimentation. For example, you should try modelling this problem using two coins; if the problem followed the predictions of most people, then when using two same-sized coins the moving one would rotate  times, but as you will see it does so twice. For example, you might predict that rolling from the top of the fixed coin to its bottom would result in the rolling coin finishing upside-down, but in fact it will have unexpectedly performed a complete rotation by this point. I highly recommend trying this yourself.

times, but as you will see it does so twice. For example, you might predict that rolling from the top of the fixed coin to its bottom would result in the rolling coin finishing upside-down, but in fact it will have unexpectedly performed a complete rotation by this point. I highly recommend trying this yourself.

If you find it difficult to grasp how things work on a circle, you might also want to imagine what would happen on a square. When a circle rolling along the outer periphery of a square encounters the first corner, it will have to rotate an "extra" 90° to continue along the next side. This will happen again at each corner, and since 90° x 4 = 360°, this accounts for an additional full revolution.

Each of the above explanations describes the circle's movement as a decomposition into rotation and revolution, but in reality no such decomposition is taking place. Just as a human's heart and lungs work simultaneously, rotation and revolution take place together. Separating revolution from rotation is helpful for understanding, but doing so does not provide a fundamental solution. Some say that the makeup of our brains does not allow for multitasking, but learning to simultaneously comprehend such phenomena would be of great value.

A similar problem appeared in Aha! Gotcha: Paradoxes to Puzzle and Delight by Martin Gardner and also in Scientific American in 1868. If you can think of an alternative proof or explanation for this problem, please post a comment or email us!

About the author

Yutaka Nishiyama is a professor at Osaka University of Economics, Japan. After studying mathematics at the University of Kyoto he went on to work for IBM Japan for 14 years. He is interested in the mathematics that occurs in daily life, and has written ten books about the subject. The most recent one is The Mysterious Number 6174: One of 30 mathematical topics in daily life, published by Gendai Sugakusha in July 2013 (ISBN978-4-7687-6174-8). You can visit his website here.