Einstein as icon

Albert Einstein around 1905.

Scientific celebrity has a relativity all of its own. Some scientists are celebrated by their peers, some are treasured by their students, while others are lionized by the public at large. But very few are given the burden of being a celebrity to everyone, everywhere, all the time. Albert Einstein achieved that universality. Publicists must despair that he did so in the pre-television era, without an agent or the help of a public-relations company. He didn't even have a website. More striking still, I doubt that more than a handful of readers have ever seen a colour photograph or a film of Einstein, and even fewer know what his voice sounded like. Yet his face has become an icon for wisdom, imagination, creativity and concentrated mental power; his brand name so pervasive a synonym for genius that even he once had to confess: "I am no Einstein."

There have always been scientific celebrities. Isaac Newton was the ornament of his age: people talked about him, made fun of him, and even devised newtonian models of government and morals. But Newton never became an icon. Instead, he remained severe and aloof. In the nineteenth century, Charles Darwin became, with Thomas Huxley's assistance, a reluctant public intellectual. Although he kept to the wings, his ideas were centre stage in long-running controversies about science and religion, the origins of humankind and our relationship to the hairier members of the animal kingdom. In retrospect, what is interesting about Darwin's work is that at some popular level it was too well known. People thought that they could understand what he was saying. Indeed, that was the problem — they understood too well.

Einstein restored faith in the unintelligibility of science. Everyone knew that Einstein had done something important in 1905 (and again in 1915) but almost nobody could tell you exactly what it was. When Einstein was interviewed for a Dutch newspaper in 1921, he attributed his mass appeal to the mystery of his work for the ordinary person: "Does it make a silly impression on me, here and yonder, about my theories of which they cannot understand a word? I think it is funny and also interesting to observe. I am sure that it is the mystery of non-understanding that appeals to them...it impresses them, it has the colour and the appeal of the mysterious."

Relativity was a fashionable notion. It promised to sweep away old absolutist notions and refurbish science with modern ideas. In art and literature too, revolutionary changes were doing away with old conventions and standards. All things were being made new. Einstein's relativity suited the mood. Nobody got very excited about Einstein's brownian motion or his photoelectric effect but relativity promised to turn the world inside out.

The fact that it was supposedly understood by a mere handful of people on the planet was a comfort and added cachet. You didn't need to try to understand and no-one would think you stupid for not knowing. Especially appealing was the fact that Einstein's ideas about space and time used familiar words, such as mass and energy, but endowed these words with new and richer meanings. Everyone knew what these words meant, but sentences, such as "everything is relative" or "moving clocks run slow" did not by themselves convey useful information. This irony was beautifully captured by Rea Irvin's cartoon for the New Yorker Magazine in 1929, which showed a New York street scene composed of a baffled road sweeper scratching his head surrounded by tradesmen and passing shoppers in various poses of puzzlement. The caption quotes Einstein: "People slowly accustomed themselves to the idea that the physical states of space itself were the final physical reality."

Einstein's celebrity began in 1919 when the British Eclipse expeditions confirmed his prediction of the bending of light by the Sun. This was headline news and in the years following the misery of the First World War it recreated a sense of order and hope about the Universe and human enquiry. Pictures of Einstein then were quite different. In 1905, he was a dapper young man working in a Swiss patent office. He was usually shown in a smart European-style suit, wing collar and bow tie, and would be instantly recognizable as an archetypal European professor.

After the Second World War, Einstein moved to Princeton where he became increasingly isolated from the main currents of development in theoretical physics because of his aversion to quantum theory. With no research group or school of students, he pursued a solitary search for an extension of the general theory of relativity. His aim was to unite relativity with the theory of electromagnetism and produce a unified field theory — the forerunner of today's theories of everything. It is from this latter part of his life that his iconic legacy principally derives. The slightly bohemian looking, dishevelled old gentleman with the sad eyes became the symbol of the power of the mind.

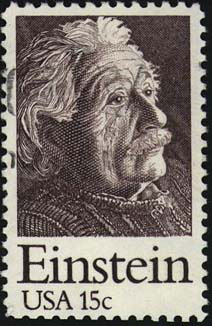

There are several things about Einstein's delayed celebrity that are interesting. First, Einstein's image in America contrasts sharply with that of the smart young man from Switzerland who made the acclaimed discoveries. The ubiquity of the older Einstein image meant that the concept of the scientific genius became associated with the image of an old fatherly figure.

The other great Einstein transformation, which occurred as the icon was emerging, is in some ways more interesting. This was in the style of his scientific work. In the brilliant papers of 1905, we see the hallmark of the young Einstein: penetrating ideas, motivated by crucial thought-experiments and finally fashioned into perfect form by mathematics that is "as simple as possible but no simpler". Yet the development of the general theory of relativity introduced Einstein to the power of abstract mathematical formalisms, notably that of tensor calculus. A deep physical insight orchestrated the mathematics of general relativity, but in the years that followed the balance tipped the other way. Einstein's search for a unified theory was characterized by a fascination with the abstract formalisms themselves. Rather than using physical arguments or thought-experiments, the strength and degrees of completeness of the formalisms themselves were used to sift their appropriateness as physical theories.

After his death in 1955, Einstein became the epitomy of intelligence in general, not just of scientific genius. His image appeared on postage stamps and magazine covers. He became the subject of poetry, sculpture and painting. "Einstein advertisements" implied that buyers were smart to buy the product, or likely to become smart if they did. Conversely, the simplicity and ease of use of a product was endorsed by the assurance that you did not need to be an Einstein to use it. The most elaborate advertising campaign that exploited Einstein's image was the 1979 Pennaco Hosiery catalogue, intriguingly entitled "The Theory of Relativity — Fall-Winter 79". Women were exhorted to "Believe in the theory of relativity". "Fashion relates beautifully — making each part relative to the next — and thus creating fantastic total outfits. Thank you, Mr. Einstein, for the theory... and Happy 100th Birthday!"

Today, the Einstein industry is as strong as ever. I was surprised to find that I owned an Einstein suit, an Einstein toy, and inevitably an Einstein calculator. If the human race had to agree on an image to transmit to an extraterrestrial civilisation, I suspect that Einstein would be a part of it. Most amazing of all is that — despite the hullabaloo and the inevitable cynicism about celebrity in our age, especially in response to media-created icons — Einstein's scientific legacy is greater than ever. His predictions about gravity have steadily been confirmed with just a few remaining beyond the reach of our experiments. His early scientific work was an unqualified success and his personal demeanour and response to fame an object lesson to all. This is why 2005 was the World Year of Physics — Einstein's Year.

About the author

John Barrow FRS is professor of mathematical sciences at the University of Cambridge, and director of the Millennium Mathematics Project, of which Plus is a part. Professor Barrow is well known as an author and lecturer committed to the public understanding of science, and has written many books about a wide spectrum of subjects that connect science and mathematics with other human interests in the arts, history and philosophy.

He also writes Plus column outer space.