The expression that (nearly) explained the Universe

This article is the runner up of the schools category of the Plus new writers award 2009.

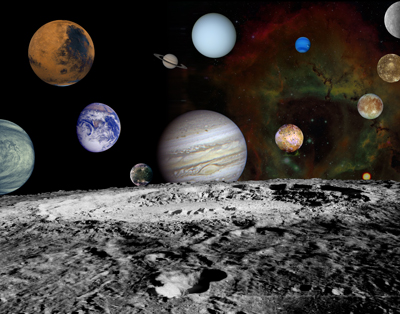

Is there a pattern in our solar system? An artist's impression of our Sun and its planets. Image courtesy NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Gazing up at the night sky, the Universe seems complex and mysterious. It is hard to imagine that something so intricate could be explained by maths so simple that even a child could understand. But that hasn't stopped people from occasionally trying.

For example, at school I am often given a sequence of numbers and asked to look for patterns in the numbers that enable me to continue the sequence. Here's an example:

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 |

What this sequence obviously does is first add 1 to 0, and from then on it doubles the previous number to get the next number. So the sequence should be continued with the numbers 64, 128, and 256. We now have

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 |

This seems pretty basic and not particularly interesting. So imagine my amazement when I discovered that for a brief period a modified version of this expression seemed to come very close to explaining the Universe!

Here's how.

Multiply each number in the sequence by 3:

| 0 | 3 | 6 | 12 | 24 | 48 | 96 | 192 | 384 | 768 |

Add 4 to each number:

| 4 | 7 | 10 | 16 | 28 | 52 | 100 | 196 | 388 | 772 |

Finally, divide each number by 10:

| 0.4 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 2.8 | 5.2 | 10.0 | 19.6 | 28.8 | 77.2 |

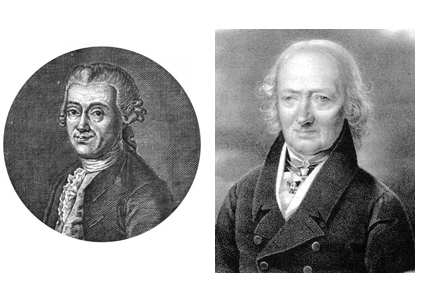

Johann Daniel Titius, left, and Johann Bode.

Why have I done all this? Well, in 1766 a German astronomer, Johann Daniel Titius, noticed that this sequence seemed to explain the average distance of each of the then known planets from the Sun (a planet's orbit is elliptical, so its distance to the Sun varies, and therefore astronomers take the average). His compatriot Johann Bode, who was the director of the Berlin Observatory, popularised this observation, which became known as the Bode-Titius rule.

The Earth is around 150 million kilometres from the Sun, a distance known as 1 Astronomical Unit (AU). The Earth is the third planet from the Sun. Mercury is the closest planet to the Sun, followed by Venus.

Guess what:

Mercury is 0.39AU from the Sun.

Venus is 0.72AU from the Sun.

Mars in 1.52AU from the Sun

The only other known planets at the time were Jupiter ad Saturn.

Jupiter is 5.2AU from the Sun.

Saturn is 9.54AU from the Sun.

These distances are pretty close to the sixth and seventh numbers in our sequence. So there seemed to be a beautifully simple pattern that accounted for the distance of the planets from the Sun. Of course, there was a gap. The sequence predicted the existence of a planet some 2.8AU from the Sun. Both Titius and Bode were convinced that there must be another planet between Mars and Jupiter, arguing that it was scarcely believable that god would have left this space empty, spoiling their model.

As well as predicting the existence of a planet between Mars and Jupiter, the Titius-Bode rule suggested that if there was a planet further away than Saturn, then it would be located roughly 19.6AU from the Sun — double the distance of Saturn from the Sun.

An artist's impression of the planet Uranus with its rings. Image courtesy NASA Ames Research Centre.

Then, in 1781, something extraordinary happened — German-born William Herschel, an amateur astronomer living in Bath, found a planet with his home-made telescope, thereby earning a place in the history books as the first modern discoverer of a planet. But Johann Bode must have felt pretty triumphant too. Firstly, it was his name for the planet — Uranus — that was eventually chosen, overriding Herschel's desire to name it after King George III (wouldn't it be weird to have a planet called George?). Secondly, Uranus was very close to where the Titius-Bode rule said it would be, orbiting at 19.2AU from the Sun.

Predicting the orbit of an unknown planet gave the rule a lot more credibility, and it started the search for the "missing planet" between Mars and Jupiter. Then Guiseppe Piazzi, an Italian astronomer, discovered Ceres on the first day of 1801. It was orbiting at 2.8AU from the Sun, just where the Titius-Bode law had predicted.

The rule had now made two successful predictions, and really did seem to reveal the secret of how the Universe had been made. Sadly, however, this was to prove the high point for the Titius-Bode rule — slowly, doubts began to set in.

The first problem was that, for a planet, Ceres was tiny. William Herschel, who considered that he had discovered a proper planet, created the word asteroid to describe Ceres. Over time, it became clear that it was just one of many objects in the so-called asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. From the 1860s onward, Ceres was no longer considered a planet. Still, one could argue that these bits of material would have formed a planet, if only they had not been disrupted by Jupiter's gravitational pull.

The second problem was that in 1846 yet another new planet was discovered and it was in the wrong place! According to the Titius-Bode rule, Neptune should be found 38.8AU from the Sun. In fact, it was quite a bit nearer than predicted.

Then, in 1930, Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto, and it was 40AU from the Sun. As more and more discoveries were made, the rule was broken down, as this table shows:

| Name | Actual distance | Predicted distance | Difference |

| Mercury | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.01 |

| Venus | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.02 |

| Earth | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Mars | 1.52 | 1.60 | 0.08 |

| Ceres* | 2.77 | 2.80 | 0.03 |

| Jupiter | 5.20 | 5.20 | 0.00 |

| Saturn | 9.54 | 10.0 | 0.46 |

| Uranus | 19.20 | 19.60 | 0.40 |

| Neptune | 30.06 | 38.80 | 8.74 |

| Pluto* | 39.44 | 77.20 | 37.76 |

Today, no-one seems to take the Titius-Bode rule very seriously. It was an idea that seemed for a while to become a scientific law, only for further data to prove it wrong. It seems its initial findings were just coincidence, and that people seized on an apparent pattern too quickly. All the same, it is still an awful lot of coincidence!

The truth is that we still know so little about our Universe, and how planets are formed, that we can't dismiss out of hand that maybe, one day, the rule will be resurrected in some form. Interestingly, it has been suggested that some moons are spaced around their planets according to a similar kind of rule. Again, it might be just that people are seeing patterns where there is only randomness. But sometimes in science, dead ideas can come back to life!

About the author

Sophie Butchart is finishing her last year at Cavendish School for Girls, Camden, before moving on to City of London School for Girls in the autumn. A keen astronomer, she can often be found stargazing from the roof of her home.