The maths sense

You don't need to count to see that five apples are more than three oranges: you can tell just by looking. That's because we, as well as many animal species, are born with a sense for number that allows us to judge amounts even without being able to count. But is that inborn number sense related to the mathematical abilities people develop later on, or is learnt maths different from innate maths?

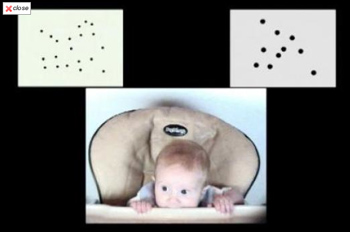

In one part of the experiments children were shown two different arrays and asked to choose which one had more dots without counting them. Image courtesy of Duke University.

New research from the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences suggests that it's the former. "When children are acquiring the symbolic system for representing numbers and learning about maths in school, they're tapping into this primitive number sense," said Elizabeth Brannon, a professor of psychology and neuroscience, who led the study. "It's the conceptual building block upon which mathematical ability is built."

Brannon and graduate student Ariel Starr worked with 48 six-months-old babies, who they sat in front of two screens. One screen always showed them the same number of dots (eg 8) which changed their size and position. The other screen switched between two numerical values (eg 8 and 16 dots) which also changed size and position. Most babies are interested in things that change, so if a baby looked longer at the screen on which the numerical values were changing, the researchers assumed that it had spotted the difference.

Brannon and Starr then tested the same children three years later. Again they were asked to judge amounts of dots without counting them. But in addition they were given a standardised maths test suitable for their age, an IQ test and a verbal task to find out the largest number word they could understand. "We found that infants with higher preference scores for looking at the numerically changing screen had better primitive number sense three years later compared to those infants with lower scores," Starr said. "Likewise, children with higher scores in infancy performed better on standardised maths tests."

This suggests that we do build on our inborn number sense when we come to learn symbolic maths using numerals and symbols. But there's no reason to despair (or excuse for laziness) if you feel you were short-changed at birth. Education is still the most important factor in developing maths ability. "We can't measure a baby's number sense ability at 6 months and know how they'll do on their SATs," Brannon added. "In fact our infant task only explains a small percentage of the variance in young children's maths performance. But our findings suggest that there is cognitive overlap between primitive number sense and symbolic math. These are fundamental building blocks."

Understanding how babies and young children conceptualise and understand number can lead to new mathematics education strategies, according to Brannon. In particular, this knowledge can be used to help young children who have trouble learning mathematical symbols and basic methodologies. The new results, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, confirm previous research into the link between our inborn number sense and later mathematical ability.