Our theory of very nearly everything: quantum fields

Having written down the equation in the last article, describing the standard model of particle physics (so capturing all the known interactions between all the known fundamental fields), we would now like to make use of it to calculate something about the particles arising in the field. For example, say we want to figure out what happens when an electron ($e$) and a positron (the antimatter partner of the electron, written as $\overline{e}$) collide. Several things could happen, but let us focus on the case where an electron and a positron emerge after the collision.

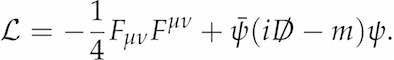

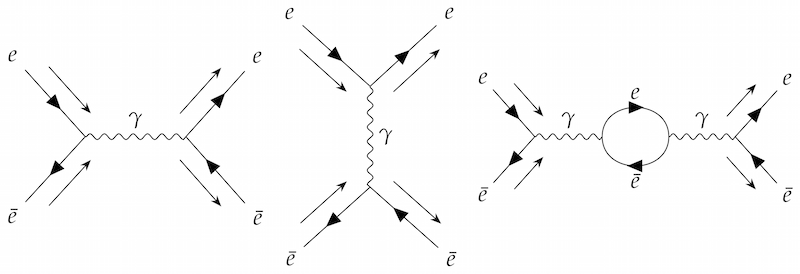

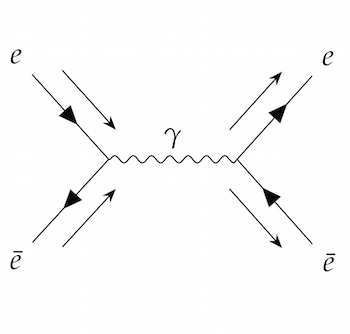

QFT provides us with the tools to compute exactly how often this process happens. We start with the equation I gave (in the last article) for the photon field interacting with the electron field

and apply the rules of quantum mechanics to it. On the face of it, the maths required is simply horrifying. But the brilliant Richard Feynman found a visual way of organising it, the so-called Feynman diagrams (earning him a Nobel Prize in 1965).

Physicists can doodle too

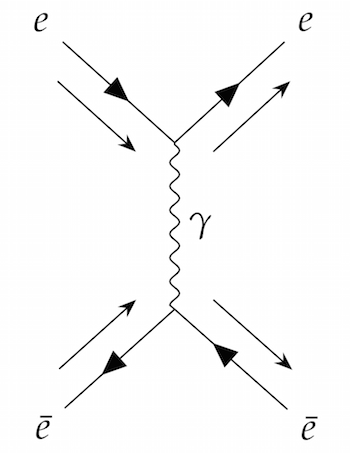

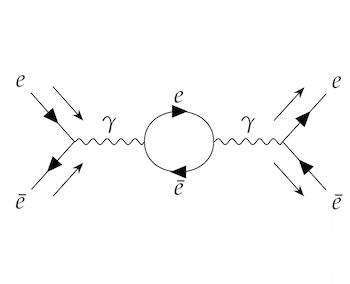

Feynman diagrams depicting some of the ways an electron and positron collision can happen

Photons are drawn as wiggly lines, while electrons and positrons are drawn as a straight line with an arrow showing which way negative electric charge is flowing. The incoming and outgoing particles have an extra arrow next to the line, showing the direction of motion.

In principle, Feynman diagrams don't depict what is actually happening in the collision; they are just a useful visual shorthand for mathematical expressions. But it is tempting, and useful for your intuition, to interpret them as movies of the collision, with time on the horizontal axis and space on the vertical axis.

For example, the first diagram looks like an electron and a positron colliding and turning into a photon, which then turns back into an electron and a positron.

The third diagram is like the first one, except that the intermediate photon spends some time as an electron-positron pair.

Feynman diagrams are useful in calculations because, although in principle you have to draw all possible diagrams (which can be arbitrarily complicated) and add them all up, in practice the simplest diagrams tend to be the most important. (You can read more about Feynman diagrams in Quantum pictures.)

The QFT rabbit hole

Quantum field theory contains a huge number of utterly fascinating details that would take many pages to explain properly. One of the great things about QFT is that it is a very rich subject – starting from its basic principles, you can reach many surprising conclusions. I am just going to give you a quick taste of two of the most important ones: symmetry and zooming.

Rotationally symmetric rabbits

In physics, a symmetry transformation is a change that has no observable effect on the world. For example, if somebody moved the whole Universe a few metres to the left, or rotated it by some amount, this would be completely impossible to detect. Symmetries are a very rich aspect of QFT. For example, the mathematical definition of a charge – like electric charge, or the less well-known hypercharge and isospin – is just a matter of how a field changes in a given symmetry transformation.

The Standard Model has quite a lot of symmetries – a lot of different charges – and the way they interplay to form the physics we observe is an intriguing subject where the Higgs field ends up "breaking" the original symmetries. This is the Higgs mechanism, the discovery that earned Peter Higgs and François Englert the 2013 Nobel Prize in physics. (You can read more in Secret symmetry and the Higgs boson.)

You might also be surprised to hear that zooming takes on a highly important role in QFT (the technical term for this is renormalisation). When we zoom in and out, the theory changes appearance, so two superficially different theories might in fact be the same theory, just at different levels of zoom. Mathematically, the Standard Model looks rather zoomed out, so we expect that it is only a zoomed out version of some unknown, more fundamental theory. Most theories get less complicated when you zoom out. The unexpected discovery that the theory of quarks and gluons actually gets more complicated when you zoom out was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2004. (You can find out more in Strong but free and Going with the flow.)

Find out about the last piece of the puzzle in the next article.

About the author

Elias Riedel Gårding grew up in Stockholm and chose physics instead of programming for his undergraduate degree because his secondary school physics class was frankly not very good, and he wanted to see what he was missing. He has always been interested in the most basic laws of nature – those of fundamental physics – but it wasn't until his master's degree in theoretical physics that he got to study them properly. He thinks quantum field theory, the basic paradigm of particle physics, deserves to be more widely known, hence this article series.